Why and When Should I Give Platelets or FFP?

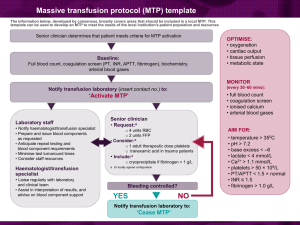

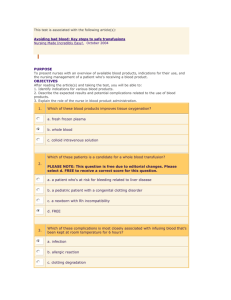

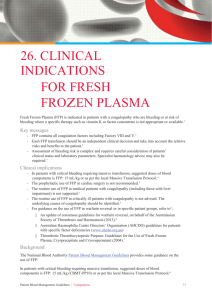

advertisement

SCA Lecture, March 2014: When should I give platelets and plasma? Stephen A. Esper, MD, MBA Ian J. Welsby, MB BS Specific Guidelines1-3 Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP): STS/SCA Plasma transfusion is reasonable in patients with serious bleeding in context of multiple or single coagulation factor deficiencies when safer fractionated products are not available. For urgent warfarin reversal, administration of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) is preferred, but plasma transfusion is reasonable when adequate levels of Factor VII are not present in PCC. Transfusion of plasma may be considered as part of a massive transfusion algorithm in bleeding patients requiring substantial amounts of red-blood cells. Prophylactic use of plasma in cardiac operations in the absence of coagulopathy is not indicated, does not reduce blood loss and exposes patients to unnecessary risks and complications of allogeneic blood component transfusion. Plasma is not indicated for warfarin reversal or treatment of elevated international normalized ratio in the absence of bleeding. ASA FFP should be given in doses calculated to achieve a minimum of 30% of plasma factor concentration (10-15 mg/kg FFP). Urgent reversal of warfarin anticoagulation may suffice with 58- ml/kg. Correct excessive microvascular bleeding in the presence of prothrombin time (PT) greater than 1.5 times normal or INR greater than 2.0, or a prothromboplastin time (aPTT) greater than 2 times normal. Correct excessive microvascular bleeding secondary to coagulation factor deficiency in patients transfused with more than one blood volume (70 cc/kg) Urgent reversal of warfarin therapy Correct known coagulation factor deficiencies when specific concentrates are unavailable Heparin resistance European2,4 Recommend against the use of FFP for pre-procedural correction of mild to moderately elevated INR. FFP may be used if no other fibrinogen source is available. Discuss the Italian guidelines that recommend transfusion of FFP when prolonged PT and aPTT (>1.5 times normal) as a trigger, or blind FFP administration if tests cannot be performed in a reasonable time.4 FFP prepared from units of whole blood and that obtained by apheresis are equivalent in terms of haemostasis and side effects In cardiovascular surgery, the routine use of apheresis procedures in the immediate pre-operative period, in order to produce platelet concentrates or units of FFP from apheresis is not recommended because the documented superiority of benefits compared to the possible risks for the patient is marginal, because it is often impossible to produce therapeutic doses of autologous blood components and because of the costs of the procedure itself The main indication for transfusion of FFP is correction of deficiencies of clotting factors for which a specific concentrate is not available, in patients with ongoing bleeding18. In the presence of acute or chronic liver disease and ongoing bleeding, DIC or active bleeding Adverse reactions to the transfusion of fresh-frozen plasma The acute adverse reactions to transfusion therapy with FFP are mild allergic reactions (urticaria) or severe, anaphylactic allergic reactions, TRALI, febrile reactions, citrate toxicity and circulatory overload18. Platelets: STS/SCA In patients requiring longer CPB times (2 to 3 hours), maintenance of higher and/or patient-specific heparin concentrations during CPB may be considered to reduce hemostatic system activation, reduce consumption of platelets and coagulation proteins, and to reduce blood transfusion. For extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: Maintain platelet count of greater than 80,000 to 100,00/mcL with transfusion. Use of intraoperative platelet plasmapheresis is reasonable to assist with blood conservation strategies as part of a multimodality program in high-risk patients if an adequate platelet yield can be reliably obtained. Preoperative hematocrit and platelet count are indicated for risk prediction and abnormalities in these variables are amenable to intervention. Patients who have thrombocytopenia (_50,000/mm2), who are hyperresponsive to aspirin or other antiplatelet drugs as manifested by abnormal platelet function tests or prolonged bleeding time, or who have known qualitative platelet defects represent a high-risk group for bleeding. Maximum blood conservation interventions during cardiac procedures are reasonable in these high-risk patients. Use of 1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin (DDAVP) may be reasonable to attenuate excessive bleeding and transfusion in certain patients with demonstrable and specific platelet dysfunction known to respond to this agent (eg, uremic or CPB-induced platelet dysfunction, type I von Willebrand’s disease). ASA In a bleeding patient, platelets should be administered when the count is below 50,000 cells/mm3 Platelet count is rarely indicated when greater than 100x109/L and is usually indicated when the count is below 50x109 in the presence of excessive bleeding. Determination of whether patients with intermediary platelet counts should require therapy, including prophylactic therapy, should be based on potential for platelet dysfunction, anticipated or ongoing bleeding, and the risk of bleeding into a confined space. If a platelet count cannot be done in a timely fashion in the presence of excessive microvascular bleeding, platelets may be given if thrombocytopenia is suspected. Prophylactic transfusion of platelets for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura is ineffective and rarely indicated. Point of Care Testing: Thromboelastography (TEG) Rotational Thromboelastometry (ROTEM) Functional Platelets Activated Clotting Time (ACT) European Guidelines: 5.1.7 Are patient outcomes improved by algorithms that incorporate coagulation monitoring for perioperative haemostatic management? Recommend the application of transfusion algorithms incorporating predefined intervention triggers to guide haemostatic intervention during intraoperative bleeding. 1B Recommend the application of transfusion algorithms incorporating predefined intervention triggers based on POC coagulation monitoring assays to guide haemostatic intervention during cardiovascular surgery. 1C Article on Point of Care Testing: Hemostatic therapy based on point of care testing reduced patient exposure to allogenic blood products and provided significant benefits with respect to clinical outcomes. Weber CF and Gorlinger K et al. Point of Care Testing: A Prospective, Randomized Trial of Efficacy in Coagulopathic Cardiac Surgery Patients. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:531-547. Risk of Transfusion: Transfusion Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI) Acute Immune Hemolytic Reaction Delayed Hemolysis Graft-versus-host disease Allergic reaction and anaphylaxis Fever Infections o Hepatitis B o Hepatitis C o HIV o Bacterial Contamination 1. Ferraris et al. 2011 Update to The Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Blood Conservation Clinical Practice Guidelines. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2011;91:944-82 2. Kozek-Langenecker SA et al. Management of severe perioperative bleeding, Guidelines from the European Society of Anesthesiology. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2013;30:270-382. 3. American Society of Anesthesiology Task Force on Perioperative Blood Transfusion. Practice Guidelines for Perioperative Blood Transfusion and Adjuvant Therapies. Anesthesiology. 2006. 105;1:198-208. 4. Liumbruno GM, Bennardello F, Lattanzio A, et al. Recommendations for the transfusion management of patients in the peri-operative period. II. The intra-operative period. Blood Transfus 2011; 9:189–217.