Claire - Dickinson and HD

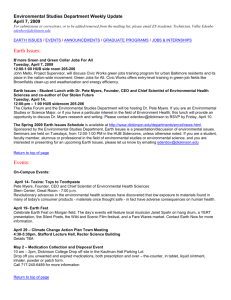

advertisement

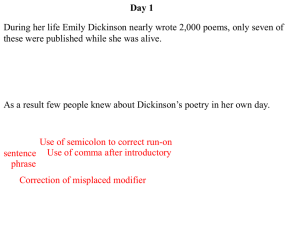

Claire Tuley ED Paper 2/25/2011 Emily Dickinson’s poetry was meant to be interpreted in several ways. Multiple versions of poems exist, either through rewrites or embedded into letters. When collected together, the different versions of poems prompt contradictory readings due to the variants and changes made between versions. The variants that are included with certain poems indicate audience participation—rather than choose just one word, she allowed her reader to pick the one that they thought best suited the work. In some poems, the variants are minor; words are made plural or “the” is switched to “a.” But in others the variants are major, such as Poem #57, the first line of which varies between “I robbed the Woods-” and “Who robbed the Woods-”. The two versions show that by changing the poem’s subject, Dickinson challenged her readers to reinterpret its meaning. Dickinson used the variants to experiment with questions of identity, authority, and nature. It is difficult to say if there is one correct version; rather, the two variations of the poem indicate that Dickinson was aware of the power of language early in her writing career. The earliest version of the poem is dated to 1859. Unlike Dickinson’s other poems, where identifying the subject is difficult, she immediately identifies the speaker as the subject of the poem: “I robbed the Woods-” (1). By posing the speaker as a robber, the reader is encouraged to regard the speaker’s actions as wrong. Dickinson continues this through her descriptions of the forest. The woods that she robbed are described as "trusting" (2) and "unsuspecting" (3). Not only does Dickinson position the woods as the innocent party, she also humanizes them by using two adjectives that are often applied to people. The speaker continued her robbery when she “brought out their Burs and mosses” (4). These are not anthropomorphized like the woods and trees, but the plants that she picks have their own distinctive characteristics. The burs immediately bring to mind thorns that act as protection. The burs are juxtaposed with the softness of the moss. By contrasting the sharp and soft, Dickinson shows the range of life in the woods. Though these are not anthropomorphized in the same manner as the trees, the burs and the moss could stand in for different types of ‘personalities’ in the forest. Instead of a mass of trees, there is a varied life within in the woods. By taking out the burs and moss that augment the woods, the speaker is robbing the forest of the features that make each tree original. The speaker says that she steals from the forest because it is her “fantasy to please” (5). The structure of the line implies a lack of agency for the speaker. She is not using the fantasy to please herself; rather, she is trying to placate her fantasy. This is supported by the following line, “I scanned their trinkets curious-” (6). In Dickinson’s 1844 edition of Noah Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language, ‘scan’ is defined as “To examine with critical care; to scrutinize.” The speaker is looking for something in particular to please the fantasy. When she finds what she was looking for, she holds on to it tightly. “I grasped- I bore away” (7). Dickinson does not identify or describe what she has found. The easiest interpretation is that she’s found something to the mosses and burs; however, by not defining what it is she has found Dickinson has created an internal variant for her reader. The dashes that replace the noun allow the reader to insert into that space what they find most appropriate. After the speaker steals her prize from the forest, Dickinson ends the poem with “What will the solemn Hemlock- / What will the Oak tree say?” (7-8). By capitalizing the names of the trees, Dickinson once again humanizes them for her readers. She goes further by calling the hemlock solemn. Dickinson’s edition of Webster’s includes the definition of solemn as religiously grave or serious, but the first definition listed in the dictionary is “Anniversary; observed once a year with religious ceremonies.” Though the editor doubts the accuracy of the definition, it does imply a certain ritual associated with the hemlock. That hemlock is poisonous suggests that the ventures into the woods are a regular put dangerous practice; however, it is possible that Dickinson looked beyond its poisonous properties. Domhnall Mitchell writes that Dickinson identifies hemlock “with northern climates and races (such as her own)” and “is nature's aesthete, a saint in the wilderness, a representative of those few people who yearn for the subtle and not the spectacular” (Mitchell 79). If the forest is to stand for different sorts of personalities, Dickinson could have included the hemlock as a reference to her own character. In this way, the speaker is stealing a part of her personality. Whether or not Dickinson identified similar traits between herself and the hemlock, its inclusion in the poem suggests at first glance an almost dangerous relationship with nature. Dickinson furthers this by following hemlock with a dash, suggesting a quick and deadly termination to the sentence. In the final line, Dickinson gives the oak tree its own agency by alluding to its ability to speak. Though the tree is not the poem’s speaker, the “will” implies that it is capable of speech and judgment. By ending with a question, Dickinson leaves the poem in a state of uncertainty. If the oak tree can somehow express its feelings, what would it say? Words that compare the speaker to a thief, such as “robbed,” “grasped,” and “bore away” would imply that it would denounce the speaker’s actions. This reading implies that Dickinson is judging the man’s destructive relationship with nature by putting the forest in a sympathetic and humanized light. Another way of looking at the poem puts the speaker’s actions into a very different perspective. When Dickinson writes that the speaker “scanned their trinkets,” she gives the poem multiple meanings. This could mean that the speaker was simply looking at the forest’s features; however, Dickinson’s dictionary also defines scan as “To examine a verse by counting the feet.” Scan’s alternate definition changes the possible meaning of the poem. By approaching the actions with the woods through poetic terms, Dickinson presents a poem about writing in which the speaker goes into the woods for inspiration. The etymology of the word moss provided by the dictionary indicates that in Greek, the word also stood in for shoots or twigs. With this definition, the mosses that the speaker brings out are new ideas. In Dickinson’s dictionary, burs are defined as “rough prickly covering of the seeds of certain plants” which could indicate difficulties of uncovering inspiration during the creative process. The alternate definitions make it possible to read the poem as about an author going to nature for inspiration. “What will the Oak tree say?” can be taken to mean “What will the oak tree say to the author?” By ending it on a question, Dickinson demonstrates that poems are not created the instant one comes in contact with a creative source; rather, it takes time to find the inspiration. An 1861 manuscript edition of the poem continues with the writer-as-robber theme; however, this version has one very major change. In this version, the speaker is never identified. Instead of declaring who robbed the woods, the poem begins “Who robbed the Woods-” (1). This interrogative is furthered by a change made to the punctuation at the end of the second line. Instead of a dash, the line ends with a question mark which turns these two lines into a clear question. By making this change, Dickinson not only shifts the blame from the speaker but also indicates that there might not be a definitive answer to the question. Beyond shifting the subject from the speaker to an unknown, a further change is made to subject. In the first version, it can be assumed that the speaker is female though she is never identified beyond the pronoun “I.” In the 1861 version, the subject is identified as male. If this is a poem about a poet, then it is significant that Dickinson clearly makes the subject male. A male subject in a piece about the poetic process would be more appropriate to the expectations of the time that the author is naturally male. The male subject also makes it less obvious that the piece is about Dickinson’s poetic power. Instead, by using a male subject, Dickinson presents a more conventional piece about a strong male figure taking what he needs in order to fulfill his poetic fantasy; however, this is completely at odds with the 1859 version of the poem. In Adrienne Rich’s essay “Vesuvius at Home: The Power of Emily Dickinson,” she provides a view of Dickinson’s poems that offers one explanation for such a radical change between the two versions. Rich proposes that in Dickinson’s poems about the poet’s relationship to her power, she presents the poetic muse as male (Rich, 181). With this reading, it is the muse who becomes a destructive force and robs the woods. This also helps to redefine “robbed.” Dickinson’s edition of Webster’s lists one definition of robbed as “To plunder; to strip unlawfully; as, to rob an orchard; to rob a man of his just praise.” Though the definition indicates a robbery of tangible property, the second example shows that it can be figurative as well. Using that definition, one possible reading of the opening line “Who robbed the Woods-” reveals that the muse is robbing the woods of its glory by using it as inspiration. This interpretation suggests that writers have a destructive relationship with nature because they capture nature’s beauty and keep it on the page. Dickinson’s poems defy one definitive reading. At first glance, poem #57 is simply explained away as a robbery in the woods; however, a second look reveals that Dickinson layered on several different meanings. The variants, from those that differ between the 1859 and 1861 copies to those suggested by the dashes, create multiple interpretations. This poem addresses not only man’s destructive relationship with nature, but also the gendered power of the poet and the forces of inspiration. Works Cited Dickinson, Emily. The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition. Ed. R. W. Franklin. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005. Print. Dickinson, Emily. The Poems of Emily Dickinson. Ed. R. W. Franklin. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998. Print. Mitchell, Domhnall. “Northern Lights: Class, Color, Culture, and Emily Dickinson.” The Emily Dickinson Journal 9.2 (2000): 75-83. Project Muse. Web. 23 February 2011. Rich, Adrienne. “Vesuvius at Home: The Power of Emily Dickinson.” Critical Essays on Emily Dickinson: 175-194. Web. 25 February 2011.