here - Dr Peter Hersey MBChB FFICM EDIC FRCA DipMedEd FHEA

advertisement

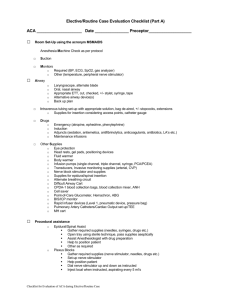

Protocol: The Development and Evaluation of a Learning Package for Airway Assistants in the Emergency Department. Chief Investigator Dr Peter Hersey Consultant in Anaesthesia and Critical Care City Hospitals Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust Sponsor (Academic) Dr Sean McAleer Course Director and Senior Lecturer Centre for Medical Education University of Dundee Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 Title The Development and Evaluation of a Learning Package for Airway Assistants in the Emergency Department. Rationale The induction of anaesthesia may be required in the emergency department as part of the resuscitation and stabilisation of a patient. The technique used is known as a rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia, or RSI. The doctor undertaking the RSI requires an assistant, who may be an anaesthetics nurse, an operating department practitioner or an emergency department nurse. For the emergency department nurse, assisting an RSI may not be a regular task or one in which they have received formal training. The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) specify in their guideline ‘The Anaesthesia Team 3’ (AAGBI, 2010) that the anaesthetist must have ‘dedicated qualified assistance’ and the Nursing and Midwifery Council state that a nurse must recognise and work within the limits of their competence (NMW, 2008). This project considers how to deliver efficient and specific training to the emergency department nurse. Overview of Existing Research 1.2 Defining the problem More than 25 years ago, James and Ilsom (1988) conducted a survey of anaesthetists providing general anaesthesia in the emergency department. They reported that 64% of anaesthetists surveyed had an emergency nurse as their assistant, with 8% having no assistant and 29% being assisted by an anaesthetics nurse or ODP. 68% of anaesthetists surveyed thought their assistance was inadequate. In their conclusions, the authors write: “Surely it is unreasonable to expect people to perform tasks for which they are not specifically trained and then criticise them for the way in which these tasks are carried out” and “it seems reasonable that nursing staff should be given the opportunity for suitable Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 training, with regular review, as with other extended roles of the nurse” (James and Illson, 1998) Once stabilised, the critically ill patient may require transfer to a tertiary centre for ongoing care. Whilst the nurse acting as the second attendant for transfer is required to be competent in areas other than those required of an airway assistant, the ability to assist at an RSI is an area of competence mandated by the Intensive Care Society for safe patient transfer (Intensive Care Society, 2011). Stevenson et al. (2005) report a UK national survey of critical care transfers from the emergency department, reporting that only 2% of emergency departments had formal training for nursing staff in patient transfer, with informal training and supervised practice in 64%. The authors do not consider whether the second attendant was trained specifically in the airway assistant role however such evidence suggests that training for emergency department nurses may be lacking for areas out with their scope of frequent practice. 1.3 The relationship between training and competence Formal training is not required for all tasks, and training does not guarantee competence. One aspect of the airway assistant role that has been subject to assessment of competence is the application of cricoid pressure. Cricoid pressure is used to help prevent passive regurgitation of stomach contents. To perform cricoid pressure, the cricoid cartilage is located on the front of the neck and backwards pressure applied. A UK national survey of practice showed the use of cricoid pressure in all cases of RSI (Morris and Cook, 2001). Nafiu et al. (2009) reported that in a mixed sample of ED doctors and nurses from a large teaching hospital in the USA, 78.3% had never received any formal training on the correct application of cricoid pressure. The same survey was repeated in another centre by Black et al. (2012) who reported that 38.1% of ED nurses had never received training in the application of cricoid pressure, with a further 38.1% receiving training more than 2 years previously. Both authors also administered a questionnaire designed to test knowledge of cricoid pressure application; the mean score for the ED nurses was 42.9%, which was the lowest score in the professional groups studied. In New Zealand, Quigley and Jeffrey (2007) administered a questionnaire to 46 nurses and 26 doctors in the emergency department. 80% of those sampled had applied cricoid pressure in clinical practice, but only 53% could correctly identify a description of the location of the cricoid. Whilst this is a Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 surrogate measure for being able to locate the cricoid cartilage on a patient, the findings may indicate a failure of peer review in maintaining performance given that 80% had undertaken the task. This paper does not describe how many of the sample had received formal training. In Australia, Clark and Trethewy (2005) report that only 25% of emergency department nurses in their sample applied the correct level of force when applying cricoid pressure, highlighting a need for psychomotor as well as knowledge based training. 1.4 Teaching cricoid pressure The literature concerning teaching the correct application of cricoid pressure is significant, including systematic reviews e.g., (Gardiner and Grindrod, 2005), (Patten, 2006),(Beavers et al., 2009), (Parry, 2009), (Holmes et al., 2011), (Chewter, 2011), a meta-analysis (Johnson et al., 2013), descriptions of novel techniques e.g. (Flucker et al., 2000), (Owen et al., 2002),(Clayton and Vanner, 2002), (Kopka and Crawford, 2004), (Quigley and Jeffrey, 2007), (May and Trethewy, 2007), and descriptions of assessment e.g. (Nafiu et al., 2009), (Black et al., 2012). In their meta-analysis of 10 studies, Johnson et al (2013) report a benefit of simulation training over no training for the application of cricoid pressure with a pooled standardised mean difference of 1.18 (95% CI 0.85-1.51). Five studies considered retention of the skill, with reported retention of only 1 week to 3 months. Flucker et al. (2000) describe a cheap and simple means of teaching the force required for cricoid pressure using an air filled 50ml syringe. In comparison to other methods described, their simulator was cheap, easy to assemble and did not require any equipment that could not be easily found in a clinical area. In comparison to the other described novel simulators, Flucker et al. therefore describe a simulator which is best suited to selfdirected learning at a time and environment to suit the learner. 1.5 What is the scope of practice of an Airway Assistant? Whilst the application of cricoid pressure is an important role of the airway assistant, it does not describe it in its entirety. This research aims to define the whole scope of practice of the airway assistant in the emergency department, and only then to devise a feasible training programme. As a basis for defining this scope of practice, reference must be made to the already defined role of the anaesthetic assistant, a role including but not limited to that of the Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 airway assistant. In 2003, the Scottish Government published a report to address the challenges of variation in training and standardisation of anaesthetic assistants (Scottish Government, 2003). One of the recommendations of this report was to define a list of competencies, a revision of which was published in 2011 (NHS Education for Scotland, 2011). Whilst not all of these competencies are relevant to the emergency department nurse, there is a section entitled ‘involvement in airway management’ which could form a useful starting reference for defining the role of the airway assistant. The justification to consider only those competencies relevant is supported by the document ‘The Anaesthesia Team 3’ (2010) in which the AAGBI state: “Individuals currently working as anaesthetic assistants may not have evidence of achievement of these competencies. The AAGBI believes that such individuals, assisted by their employers, should use their personal development plans to allow them to provide appropriate evidence of achievement of those competencies relevant to their practice.”(AAGBI, 2012) 1.6 Use of the Delphi technique The Delphi technique has been utilised by others to define nursing competencies in the emergency department. Sue et al. (2010) defined competencies for nurse practitioners working within the emergency department. O’Connell and Gardner (2012) conducted a similar exercise for emergency nurse practitioners in Australia. This group also considered a whole scope of practice, utilising a focus group to identify an initial draft of competencies to be considered by the Delphi panel. 1.7 Existing training The West Yorkshire Medic Response Team (WYMRT) provide, and NHS Education for Scotland (NHS Education for Scotland, 2005) previously provided training courses for airway assistants. These courses are face to face learning events using simulation, skill stations and lectures. Such an approach has practical difficulties. Nursing staff and teaching faculty must be released from their workplace, and provide funding to attend. The capacity must also exist for every emergency department nurse, of whom there are a great number, to attend courses on a regular basis to maintain their competence. Birmingham Children’s Hospital utilise a MoodleTM course for training paediatric intensive care nurses as airway assistants outside of their PICU (Birmingham Childrens Hospital Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 NHSFT). Such an approach is advantageous in that learners can utilise the learning opportunity at a time and pace to suit themselves. The course itself is free and available to those working within the PICU, and can be revisited at a frequency to suit the learner. Practical skills, such as cricoid pressure can be described and demonstrated but not practiced with electronic learning. What can be incorporated however is guided practice with a low fidelity simulator such as that described by Flucker et al. (2000) as part of the electronic learning process. This study will utilise develop previous work in that it will consider: 1. The incorporation of existing competencies into a Delphi process. 2. The use of an e-learning package with an incorporated part task trainer to replace the established teaching method of small group teaching and simulation. 3. The production of an educational resource to address the needs of a specific group of learners. Research Questions 1. What are the behaviours required of an airway assistant for rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia in the emergency department? 2. Can these behaviours be taught using an e-learning package and part task trainer? Research Objectives 1. To modify the core competencies of NHS Scotland to make them specific for airway assistants in the ED. 2. To produce an e-learning package addressing these competencies. 3. To assess whether the educational experience has resulted in an acceptable level of confidence and competence for the learner. Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 Methodology Phase 1 A Delphi panel will be recruited using purposive sampling, consisting of two of each of the following groups: anaesthetics nurses / operating department practitioners, nurse educators, consultant anaesthetists, consultant intensivists, consultants in emergency medicine, senior emergency department nurses, intensive care medicine trainees and trainee anaesthetists. The Delphi process will consist of three rounds. In the first round panel members will be asked “What would you expect an ED nurse to be able to know and do in their role as airway assistant for a rapid sequence induction in anaesthesia? Responses will be added to those from section 4 ‘involvement in airway management’ of the already available competencies (NHS Education for Scotland 2011). All responses will be grouped by theme. Each of these statements will be evaluated in a second round by use of a Likert scale for continued inclusion (1 - Not necessary, 2 - Desirable, 3 - Important, 4 - Necessary). Those items with a mean score of 3.25 or more and any new competencies suggested at this stage will be incorporated into the final round. In the final round the panel will be asked whether they ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’ with the inclusion of the competency. Those receiving agreement from 75% of respondents will be included in the final list. At each stage four weeks will be allowed for a response, with reminders being sent after two and three weeks. Phase 2 An e-learning package will be produced with the desired outcomes being the competencies defined in phase 1. Ten volunteer nurses will be recruited by invitation. The inclusion criteria will be emergency department nurses who have not received training in airway assistance within Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 the last year. There will be no exclusion criteria. After completing the elearning package, participants will be asked to complete an embedded evaluation of the package. Ethics Social care REC, NHS R&D and NHS SSI forms will be completed. NHS REC is not required. If the e-learning package does not show an improvement in confidence and attainment of the required standard, subjects will be offered further instruction. Timeline and Project Management. After acquiring ethics approval, Delphi panel members would be recruited. I would anticipate the following timeframe: Phase 1 – 3 months post recruitment. Phase 2 – The e-learning package would be expected to take 2 months to produce. Subjects would not be recruited until the end of this process, to reduce the delay from consent to participation. Once available we anticipate a further 2 months of recruitment and participation. Potential Benefits or Outcomes As well as answering the research questions previously stated, this project aims to produce a feasible means of training and CPD provision where one does not currently exist. If made available for introduction on a wider scale the benefits to patient care would be significant. This research will be submitted to the University of Dundee as the dissertation component of the qualification Masters in Medical Education (MMEd) Data Analysis The data collection for the Delphi stage is outlined above. Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 A Likert scale will be used to quantify confidence levels pre and post the intervention. Simple statistical tests will be used under the guidance of the academic supervisor. Costings The project will be self-funded. References THE ASSOCIATION OF ANAESTHETISTS OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. The Anaesthesia team 3. AAGBI. London. 2010 THE ASSOCIATION OF ANAESTHETISTS OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. Statement on Assistance for the Anaesthetist.London 2012 BEAVERS, R.; MOOS, D.; CUDDEFORD, J. Analysis of the application of cricoid pressure: implications for the clinician. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing, v. 24, n. 2, p. 92, 2009. ISSN 1089-9472. BIRMINGHAM CHILDRENS HOSPITAL NHSFT. http://www.bchmoodle.com/course/info.php?id=163 Accessed on: 9th July 2014. BLACK, J.; CARSON, M.; DOUGHTY, A. How Much and Where: Assessment of Knowledge Level of the Application of Cricoid Pressure. JEN: Journal of Emergency Nursing, v. 38, n. 4, p. 370-375, 2012. ISSN 00991767. CHEWTER, M. Cricoid pressure: are we doing it right? Journal of Perioperative Practice, v. 21, n. 10, p. 342, 2011. ISSN 1750-4589. CLARK, RK.; TRETHEWY CE. Assessment of cricoid pressure application by emergency department staff. Emergency Medicine Australasia, v. 17, p. 376-381, 2005. CLAYTON, T. J.; VANNER, R. G. A novel method of measuring cricoid force. Anaesthesia, v. 57, n. 4, p. 326-329, 2002. ISSN 0003-2409. FLUCKER, C. et al. The 50-millilitre syringe as an inexpensive training aid in the application of cricoid pressure. European Journal of Anaesthesiology, v. 17, p. 443-447, 2000. Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 GARDINER, E.; GRINDROD, E. Applying cricoid pressure. British Journal of Perioperative Nursing, v. 15, n. 4, p. 164-169, 2005. ISSN 14671026. HOLMES, N.; MARTIN, D.; BEGLEY, A. Cricoid pressure: a review of the literature. Journal of Perioperative Practice, v. 21, n. 7, p. 234, 2011. ISSN 1750-4589. THE INTENSIVE CARE SOCIETY. Guidelines for the transport of the critically ill adult (3rd Edition 2011). London: ICS, 2011. JAMES, M. R.; MILSOM, P. L. Problems encountered when administering general anaesthetics in accident and emergency departments. Archives of Emergency Medicine, v. 5, n. 3, p. 151-155, 1988. ISSN 0264-4924. JOHNSON, R. L. et al. Cricoid pressure training using simulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Anaesthesia, v. 111, n. 3, p. 338-346, 2013. ISSN 0007-09121471-6771. KOPKA, A.; CRAWFORD, J. Cricoid pressure: A simple, yet effective biofeedback trainer. European Journal of Anaesthesiology, v. 21, n. 6, p. 443-447, 2004. ISSN 0265-0215. MAY, P.; TRETHEWY, C. Practice makes perfect? Evaluation of cricoid pressure task training for use within the algorithm for rapid sequence induction in critical care. Emergency Medicine Australasia, v. 19, n. 3, p. 207-213, 2007. ISSN 17426731. MORRIS, J.; COOK, T. M. Rapid sequence induction: A national survey of practice. Anaesthesia, v. 56, n. 11, p. 1090-1097, 2001. ISSN 0003-2409. NAFIU, O. O.; BRADIN, S.; TREMPER, K. K. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding cricoid pressure of ED personnel at a large U.S. teaching hospital. JEN: Journal of Emergency Nursing, v. 35, n. 1, p. 11-16, 2009. ISSN 00991767. NHS EDUCATION FOR SCOTLAND, N. E. F. A Guide For Assistants Working Outwith The Theatre Setting. Edinburgh: NHS Education for Scotland 2005. NHS EDUCATION FOR SCOTLAND. Core Competencies for Anaesthetic Assistants. Edinburgh: 2011. NURSING AND MIDWIFERY COUNCIL. The code: Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives. London: NMC, 2008. Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 O'CONNELL, J.; GARDNER, G. Development of clinical competencies for emergency nurse practitioners: a pilot study. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal, v. 15, n. 4, p. 195, 2012. ISSN 1574-6267. OWEN, H. et al. Learning to apply effective cricoid pressure using a part task trainer. Anaesthesia, v. 57, n. 11, p. 1098-1102, 2002. ISSN 00032409. PARRY, A. Teaching anaesthetic nurses optimal force for effective cricoid pressure: a literature review. Nursing in Critical Care, v. 14, n. 3, p. 139, 2009. ISSN 1362-1017. PATTEN, S. P. Educating nurses about correct application of cricoid pressure. AORN Journal, v. 84, n. 3, p. 449-457, 2006. ISSN 00012092. QUIGLEY, P.; JEFFREY, P. Cricoid pressure: assessment of performance and effect of training in emergency department staff. Emergency Medicine Australasia, v. 19, n. 3, p. 218-223, 2007. ISSN 17426731. THE SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT. Anaesthetic Assistance: A strategy for training, recruitment and retention and the promulgation of safe practice. Scottish medical and scientific advisory committee: The Scottish Government 2003. STEVENSON, A. et al. Emergency department organisation of critical care transfers in the UK. Emergency Medicine Journal, v. 22, n. 11, p. 795-799, 2005. ISSN 14720205. STEVENSON, A. G. et al. Tracheal intubation in the emergency department: the Scottish district hospital perspective. Emergency Medicine Journal, v. 24, n. 6, p. 394-7, 2007. ISSN 1472-02051472-0213. SUE, K. et al. Nurse Practitioner Delphi Study: Competencies for Practice in Emergency Care. JEN: Journal of Emergency Nursing, v. 36, n. 5, p. 439-450, 2010. ISSN 00991767. WEST YORKSHIRE MEDIC RESPONSE TEAM. http://www.wymrt.co.uk/education/training/training.html, Version 2.0, 28th August 2014 Accessed on: 9th July 2014.