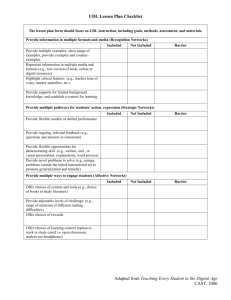

The Effect of Presentation Format on Functional Fixation in a Digital

advertisement