Cuneiform

advertisement

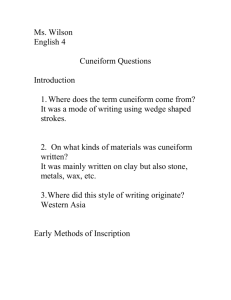

Cuneiform Pictograms, or drawings representing actual things, were the basis for cuneiform writing. As shown in the chart, early pictograms resembled the objects they represented, but through repeated use over time they began to look simpler, even abstract. These marks eventually became wedge-shaped ("cuneiform"), and could convey sounds or abstract concepts. Sumerians created cuneiform script over 5000 years ago. It was the world's first written language. The last known cuneiform inscription was written in 75 AD. Cuneiform was later adapted by the Akkadians, Babylonians and Assyrians to write their own languages and was used in Mesopotamia for about 3000 years. The first pictograms were drawn in vertical columns with a pen made from a sharpened reed. Then two developments made the process quicker and easier: People began to write in horizontal rows, and a new type of pen was used which was pushed into the clay, producing "wedge-shaped" signs that are known as cuneiform writing. Clay tablets were the primary media for everyday written communication and were used extensively in schools. Tablets were routinely recycled and if permanence was called for, they could be baked hard in a kiln. Many of the tablets found by archaeologists were preserved because they were baked when attacking armies burned the building in which they were kept. Clay was an ideal writing material when paired with the reed stylus writing tool. The writer would make quick impressions in the soft clay using either the wedge or pointed end of the stylus. By adjusting the relative position of the tablet to the stylus, the writer could use a single tool to make a variety of impressions. While many wedge positions are possible, awkward ones quickly fell from use in favor of those that were quickest and easiest to make. Like sloppy handwriting, badly made cuneiform signs would be illegible or misunderstood. Early Sumerian Tablet…How did Cuneiform Develop? Five thousand years ago the people of Sumer began to write. They were the first, and they began not with poetry or stories or great literature, but rather with economic transactions. The tablet pictured below is one of the earliest on record. It describes the transfer of 300 acres of land between two parties. As the city states of Sumer grew in size, an increasingly complex social structure called for more sophisticated techniques to record and store accounts of economic transactions. The tablet is divided into 3 columns, which are further subdivided in panels. Solid lines mark both the columns and the panels. Reading begins at the top left (column 1), moves down the three panels on that side, and continues around the bottom edge and on to the reverse side. The text picks up again on the front at the top of column 2, which continues down and around to the back. Column 3 does the same. Column 1 describes the acquisition of 180 iku (63.5 heactares) of land by a person or temple household of a deity. Columns 2 and 3 describe how the 180 iku is divided into 4 fields. The round holes in the tablet count the bur (or field size). The Early Sumerian Tablet represents the second stage in the development of the Mesopotamian system of recording ancient economic activities. The very first stage of bookkeeping was tied to specific economic items represented by tokens, originally made from stone and then from clay. There was a specific token for sheep, another for wine, another for a day's work, etc. To record 3 sheep and 2 jugs of wine, the ancient bookkeeper would create the token for sheep three times and the token for wine twice. These tokens were then stored in a container, probably made of cloth or leather. In this first stage, quantities and items were integrally linked together. Around 3000 BC the second stage of recording economic activities began to develop. Scribes began to utilize a more complex system of notation, in which tokens were replaced by pictographs on wet clay using a reed stylus. In this second stage, quantities and items were separated. No longer were they using the token for sheep three times in order to represent three sheep, but rather they began to write the pictographic symbol for sheep alongside the symbol denoting the number three. Instead of the same symbol used three times, scribes now wrote two different symbols: one for the amount and another for the item. This was revolutionary. Numbers were now free to develop on their own into a complicated numerical designation system. Simultaneously, other written symbols were developed on a phonetic basis rather than a purely pictographic basis. This allowed for the recording of more abstract items such as names of gods, kings and humans and the recording of spoken words in addition to the recording of concrete pictograph items, like sheep and flour. With this breakthrough, the recording of written language developed so that cuneiform writing not only counted things, but could also tell stories