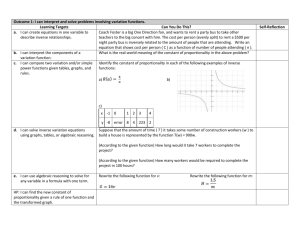

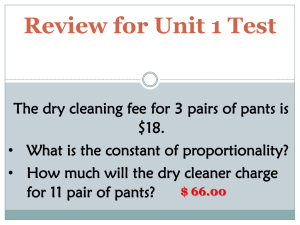

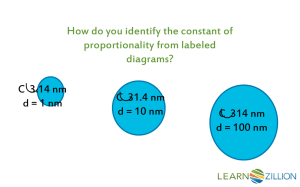

Proportionality and rationality review

advertisement