conference on

advertisement

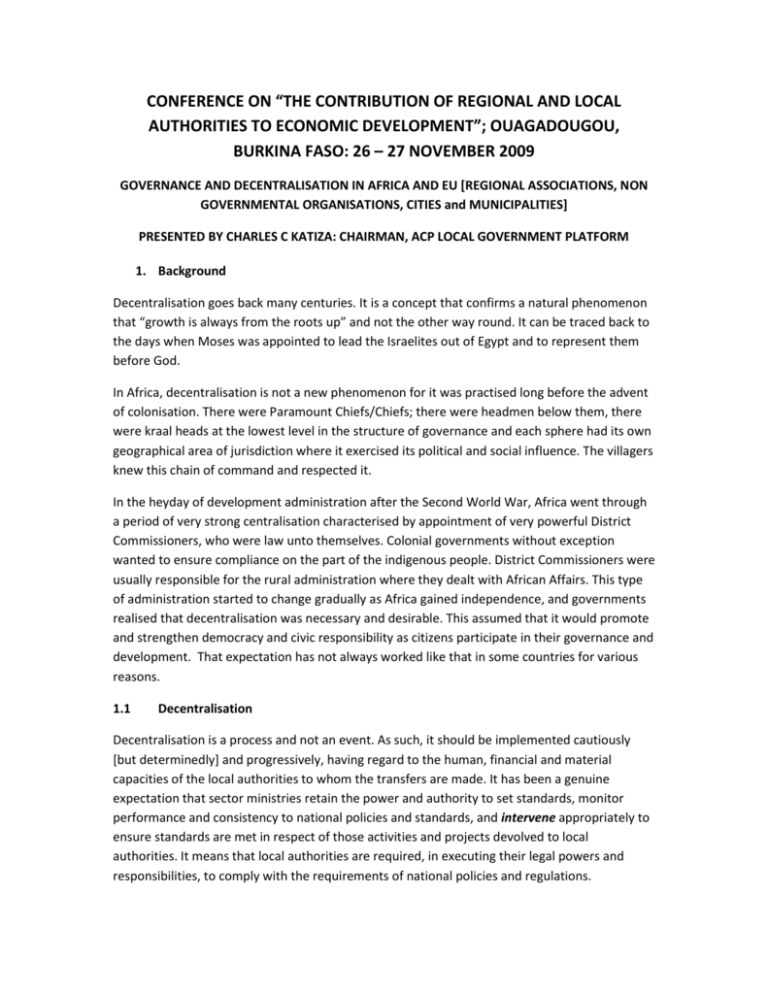

CONFERENCE ON “THE CONTRIBUTION OF REGIONAL AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES TO ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT”; OUAGADOUGOU, BURKINA FASO: 26 – 27 NOVEMBER 2009 GOVERNANCE AND DECENTRALISATION IN AFRICA AND EU [REGIONAL ASSOCIATIONS, NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANISATIONS, CITIES and MUNICIPALITIES] PRESENTED BY CHARLES C KATIZA: CHAIRMAN, ACP LOCAL GOVERNMENT PLATFORM 1. Background Decentralisation goes back many centuries. It is a concept that confirms a natural phenomenon that “growth is always from the roots up” and not the other way round. It can be traced back to the days when Moses was appointed to lead the Israelites out of Egypt and to represent them before God. In Africa, decentralisation is not a new phenomenon for it was practised long before the advent of colonisation. There were Paramount Chiefs/Chiefs; there were headmen below them, there were kraal heads at the lowest level in the structure of governance and each sphere had its own geographical area of jurisdiction where it exercised its political and social influence. The villagers knew this chain of command and respected it. In the heyday of development administration after the Second World War, Africa went through a period of very strong centralisation characterised by appointment of very powerful District Commissioners, who were law unto themselves. Colonial governments without exception wanted to ensure compliance on the part of the indigenous people. District Commissioners were usually responsible for the rural administration where they dealt with African Affairs. This type of administration started to change gradually as Africa gained independence, and governments realised that decentralisation was necessary and desirable. This assumed that it would promote and strengthen democracy and civic responsibility as citizens participate in their governance and development. That expectation has not always worked like that in some countries for various reasons. 1.1 Decentralisation Decentralisation is a process and not an event. As such, it should be implemented cautiously [but determinedly] and progressively, having regard to the human, financial and material capacities of the local authorities to whom the transfers are made. It has been a genuine expectation that sector ministries retain the power and authority to set standards, monitor performance and consistency to national policies and standards, and intervene appropriately to ensure standards are met in respect of those activities and projects devolved to local authorities. It means that local authorities are required, in executing their legal powers and responsibilities, to comply with the requirements of national policies and regulations. The subject of decentralisation is much more complex requiring political will and commitment, bargaining among administrative, economic and social sectors, bargaining among various levels of local government and inside local authorities themselves [management/councillors, councillors/traditional leaders, councillors and the communities they represent]. Therefore, implementation of any decentralisation strategy is not a simple event, rather it is a drawn out, mercy and painful process which has to be carefully thought out and closely monitored and managed, etc. It requires deliberate commitment to ensure constant resource flow and transparent management at all levels [central government and local government]. The role of local finance in the effective implementation of both decentralisation and local governance that aim to achieve the participation of all actors and the use of international money markets in order to raise additional resources and achieve a degree of fiscal autonomy are also matters local governments have continued to raise including The creation of local authorities and the emerging of local government national and regional associations saw a strong lobby for decentralisation and democratisation of local government. They called for rationalisation of resource allocation and empowerment of communities through their locally elected representatives. Local governments advocated for equitable distribution of resources and argued that central governments had the tendency to devolve mandates that were not funded. In some countries, local authorities could not borrow from external financial markets, yet resources made available by central government for capital development in country have always been very inadequate. 1.2 Central Government Response As time went on and especially in the 1960s onwards, governments started to open the lids and accepting the concept of decentralisation. This change in policy did not guarantee devolution of functions supported with resources as would have been expected. Local authorities remained starved of resources necessary for capital development. When governments accepted the principle [as a result of pressure from local government movements such as national, regional, continental and global associations], the implementation suffered serious blows from lack of technical know how or dearth of resources. Central government administrators and even politicians have tended to pay lip service. Even success stories such as the heralded Uganda, Zimbabwe, and etc .started to centralise. Attitudes have not fully changed in favour of devolution. Central administrators see strengthening of local institutions as unnecessary and a recipe for disrupting the status quo. Centralisation supported by overwhelming politicisation of the electoral process and resources limitations has significantly contributed to electoral problems such as apathy, biased electoral institutions and state media, etc , etc. External inputs into programmes such as pro-poor debates good governance, gender equity have made little impact because they have been taking place outside the realm of decentralisation. In other words, these concepts have not recognised the centrality of the municipality or district council which is in fact the planning authority in any area. That a lot of concepts such as municipal service delivery whether provided by an appointed commission, an elected council, or funded by a local or international donor, promoted outside the letter and spirit of decentralisation, have led to maladministration and corruption majority of it being devolved from the centre in some cases with full knowledge of donors . It has led citizens to receive services in ways that are not transparent and not helpful to localities unfortunately. Of late we have seen the creation of a forum for Ministers responsible for local government [AMCOD] purportedly to improve local governance. Developments such as these have seriously crowded the debate on decentralisation and good governance. This forum is poised to centralise rather than decentralise as is seen in practice. Majority of ministries of local governments are ‘mini states’ yet the debate about decentralisation is about thinning out central government so that more resources can find their way to local authorities and local development. This therefore calls for the repeal of most of our legislation in order to reduce the power and grip of local government or local administration ministers on local and regional authorities. 1.3 Governance According to Jack Jeffries “governance is the framework of social and economic systems and legal political structures through which humanity manages its affairs”. Good governance implies recognition of those around you – taxpayers, government, and civil society. Today big cities seem like “dark ages” societies with people inside and outside the wall. The environment in which we live is characterised by inclusion and exclusion whereas inclusiveness should be the hallmark of modern cities. The participation of the inhabitants in decision making is an essential means of democratic monitoring and a necessary condition for the success of poverty reduction programmes. It is a process of power sharing and an issue of major importance for the poor who also want visibility. These concerns need to be integrated in the implementation of decentralisation and good governance strategies. Accordingly, there misconceptions especially by our governments where involvement of civil society in governance issues is perceived as acts of distablising or undermining legitimacy of seating governments. It is here where experience sharing at various levels can help African nations. It is a well established fact that the successful working of democratic governance owes much to local government. It is for this reason that world governance has realised that local government plays an important role in peace building as It allows the various political, religious and ethnic groups in a society greater representation and participation in decision making, thereby increasing their stake in maintaining political and social stability. Hayek states that “nowhere has democracy ever worked well without a great measure of local self government. In terms of development outcomes, local governance processes, where public institutions and individuals are in very close relationship, are particularly relevant for service delivery in many sectors and forms, but also for the sustainability and effectiveness of territorial development strategies. Democratic local governance implies responsive and accountable local authorities (as key development stakeholders and focal point for delivery of services) and enables civil society to play its role as an integral partner in development. In terms of development outcomes, local governance processes, where public institutions and individuals are in very close relationship, are particularly relevant for service delivery in many sectors and forms, but also for the sustainability and effectiveness of territorial development strategies. Democratic local governance implies responsive and accountable local authorities (as key development stakeholders and focal point for delivery of services) and enables civil society to play its role as an integral partner in development. Governance concerns the state's ability to serve the citizens. It refers to the rules, processes, and behaviours by which interests are articulated, resources are managed, and power is exercised in society. The way public functions are carried out, public resources are managed and how public regulatory powers are exercised is the major issue to be addressed in this context. In spite of its open and broad character, governance is a meaningful and practical concept relating to the very basic aspects of the functioning of any society and political and social systems. It can be described as a basic measure of stability and performance of a society. As the concepts of human rights, decentralisation and democracy, the rule of law, civil society, decentralized power sharing, and sound public administration gain importance and relevance; society develops into a more sophisticated political system, and governance evolves into good governance1. In my view, local government processes relate to the well being of the community. They bring harmony to society which creates good conditions for development. Consequently, stability, harmony, and development are among the key words that should capture any debate on the future of Africa. Having said that, it is important to ensure that development debates between Africa and Europe are properly focused. I mean that we define clearly our agenda so that we talk about the same thing e.g. developing appropriate tools that help us package to develop the much needed capacity in African institutions and communities; create incentives for amicable information sharing between us [local institutions] and central authorities on the one hand and between African institutions and European institutions on the other hand. 2 Role of European Union - [Regional Associations, NGOs, Cities and Municipalities]. A few years ago, the Lome Convention was replaced by the Cotonou Agreement, and also the widely publicised Europe/Africa Conference was held in Paris. Most of us on the ground expected a positive change in the relations between the EU Regional and Local Institutions and those from Africa (and elsewhere). We have raised this in Brussels and many other capitals of Europe so many times, but there does not appear to be a clear direction as to where we are going and how. There appears to be more centralisation of decision making and restriction on the development resources available to developing Africa let alone the process of securing that which is available. One gets an impression that regional and national associations have taken a role as agencies of the EU/EC; whereby African and other developing country institutions have to use them as entry points into the EU or is this just my perception? These are some of the small but critical questions that should be clarified so as to help the EU come up with more coherent and predictable policy positions that help to strengthen our relations. Indeed, there have been many themes that purported to bring African and European local institutions together – for example International Municipal Cooperation [MIC]/Twinning, Decentralised Cooperation, Decentralisation, Democratisation and Development [DDD], and other concepts, etc. How far have these gone, what contribution have they made, where are the promoters of these noble ideas? As far as I know not all of them are late. But, it is because of the issues like what honourable Dutch Minister of Development cooperation pointed out that stifle some of these noble ideas. Of course there will always be reasons given such as those contained in Honourable Eveline Herfkins’ famous speech of October 2001: I quote: “Effective institutional development and capacity building require a radical break with outmoded ideas and practices. I am glad that this first Pan African Capacity Building Forum is focusing on the need for a profound change in the interaction between donors and recipients. That was something we talked about at length during the second ECA Table conference in Amsterdam last week. When it comes to donor support for capacity building, technical assistance has always been a sensitive issue. Back in 1993, the Berg report levelled severe criticism at the unimpressive results of technical assistance. Even before that, Kim Jaycox, then World bank VicePresident for Africa, made the case that expatriate technical assistance undermined African capacity. We cannot pretend that the situation has changed much since then.” Listen to this passage from "Can Africa claim the 21st Century" and I quote: "Despite massive technical assistance, aid programmes have probably weakened capacity in Africa. Technical assistance has displaced local expertise and drawn away civil servants to administer aid funded programmes - precisely the opposite of the capacity building intentions of donors and recipients". So who would dare to question that we really need a profound change? Today I want to draw your attention to three key changes that need to take place in the field of institutional development and capacity building……… she gave these as new way of thinking, new way of seeing and new way of working” Having said that, I urge this conference to seriously consider and note the following inputs: a) A concerted effort to strengthen the decentralisation process by removing bottlenecks that are undermining effective decentralisation such as lip service; support efforts to constitutionalise and rationalise legal frameworks within which local governments are operating in Africa. The decentralisation agenda has to be decongested to enable it to move progressively forward. That any new initiatives that we introduce should acknowledge and be anchored around the centrality of local government. We have seen it work in Europe; we have seen how their governments acknowledge the role of national and regional associations including the European Commission itself which is not the same as our institutions. One can draw a very close parallel ACPLGP between EPRLG. They are not treated in the same way by the Commission yet they have similar objectives in terms of what they represent in their respective constituencies? Let us work towards strengthening African institutions so that they are able to defend their respective constituencies be it local, central or civil society. More often there is no harmony between our local governments and the civil society organisations simply because they have different perceptions some of which arise from funding objectives/or mechanisms. Who is funded to do what and by whom? b) Capacity building In terms of our thinking, both the Europeans and Africans must get rid of the myths that now control their thinking and therefore distort their focus. Because we provide aid or technical assistance, we must follow and control the way things are done by sending “experts”, etcetera. You become so focussed on justifiable expenditure of donor funds that you lose sight of what it's really all about: ownership and development of local capacity. Vested interests in the development industry are hiding behind do-good intentions that in the end may not be doing so much good at all. But the myth lives on in the South too. We, as recipients, have been brainwashed by this counter-productive paradigm, which manifests itself in an outmoded collection of instruments, heave on parallel activities like project implementation units. [Expertise at local level in Zambia and Zimbabwe, for example]. In conclusion I would like to put forward the following ideas: I Multi-level governance depend on decentralised structures for its success. Centralised structures based on deconcentration have not proved to be a good development option in most African countries hence central governments conceded to decentralisation with devolution. Command structures like we had before decolonisation are a recipe for conflict as these structures concentrate power and wealth in the hands of small cliques. 2. With respect to training and institutional capacity building; it is important in the first place to take stock of resources available in the whole sector e.g. local government before we design the type of training to be introduced such as: 2.1 In service training for those already in the system so that they are acquainted with changes taking place in their sector and adapt to new systems of production. 2.2 Function related training is important so that the incumbents can specialise whilst they are also given certain generalist on then job training [for example being oriented on financial matters – Finance for non finance managers]. These approaches have been tried and they work to the benefit of councils. This applies to managers and elected officials alike. 2.3 Internal cross sector appreciation programmes that bring people from different groups in society (CBO, NGO, Govt, industry & commerce) together so that they can appreciate their different roles and how they relate to the planning authority which is the local authority. 2.4 Professional/Technical training is vital. This can be spread across different special colleges and tertiary institutions – but consider the orientation of trainers vs. the services offered by local authorities. Local authorities should be encouraged to adopt succession development strategies – where training is not haphazard but a deliberate policy that has a standing allocation in the budget (e.g. city of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe). It is necessary to decide on who carries out what type of training, where and how? Where do local experts come in what numbers? Is there need for expatriate expertise and on what terms? 3 The question of further decentralisation to local authorities in Africa and involvement of civil society is quite pertinent. But in addressing that question, there are several other issues to take note of such as the extent to which the current decentralisation has gone especially when one is agilely reminded of the current recentralisation thrust [e.g. in Uganda, Zimbabwe, Botswana, to name but a few examples in the Anglophone countries let alone in the Francophone states. However, it makes more sense to involve civil society at sub local authority level such as ward, neighbourhood and village levels. These are not new creations. They are there already but it is a question of providing broad training and providing resources that are needed. Resources are needed to train trainers at council and community based organisation levels who would in turn train the grassroot structures bearing in mind that this level is quite sensitive as governments often become suspicious. Hence the reason for using local authorities and appropriate government structures to do the work without losing site of the fact that this is a local authority programme. M Herbert – Library Media Specialist, Randolph Central School Charles C Katiza – Paper prepared for a Conference on Investment in the City of Harare, Zimbabwe Jack Jeffries – Chairman of Trustees of World Humanity Action Trust [WHAT] Jethro – as recorded in Exodus Chapter 18 Eveline Herfkins – Dutch Minister of Development Cooperation, The Hague, October 2001. Communication on Governance and Development, October 2003 (03) (615).