ASAP: Education in Emergencies

advertisement

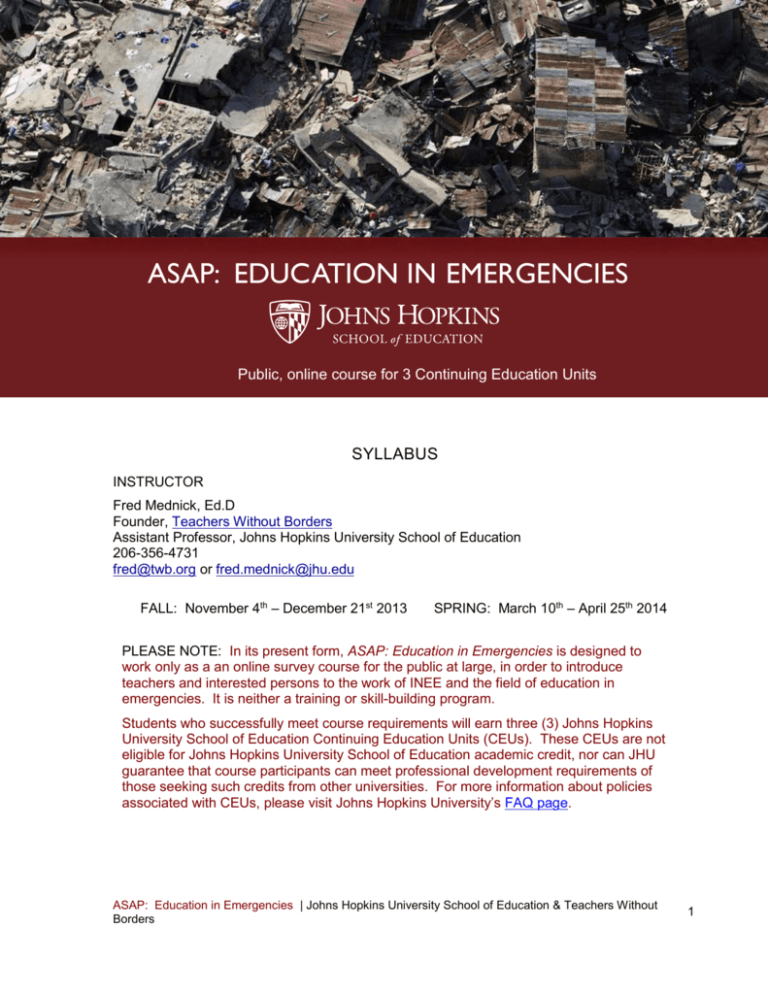

ASAP: EDUCATION IN EMERGENCIES Public, online course for 3 Continuing Education Units SYLLABUS INSTRUCTOR Fred Mednick, Ed.D Founder, Teachers Without Borders Assistant Professor, Johns Hopkins University School of Education 206-356-4731 fred@twb.org or fred.mednick@jhu.edu FALL: November 4th – December 21st 2013 SPRING: March 10th – April 25th 2014 PLEASE NOTE: In its present form, ASAP: Education in Emergencies is designed to work only as a an online survey course for the public at large, in order to introduce teachers and interested persons to the work of INEE and the field of education in emergencies. It is neither a training or skill-building program. Students who successfully meet course requirements will earn three (3) Johns Hopkins University School of Education Continuing Education Units (CEUs). These CEUs are not eligible for Johns Hopkins University School of Education academic credit, nor can JHU guarantee that course participants can meet professional development requirements of those seeking such credits from other universities. For more information about policies associated with CEUs, please visit Johns Hopkins University’s FAQ page. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 1 Table of Contents Course Overview .............................................................................................................. 2 Credits and Grading Criteria ............................................................................................. 4 Technology and Public Blog Posting Requirements ......................................................... 4 Essential Course Policies ................................................................................................. 5 Course Readings and Media ............................................................................................ 6 Online Public Events/Webinars: Conversations with Colleagues ..................................... 6 MODULES ....................................................................................................................... 7 Getting Organized | Getting Acquainted ..................................................................... 7 The Wrong Place at the Right Time: Introducing INEE .............................................. 9 If Only: Gaps and Connections Between International Development and Global Aid 11 Drilling Down, Digging Out, Delivering Education: The INEE Toolkit ........................ 13 Momaland: Case Study and Assessment Strategies ................................................ 20 Support from Viewers Like You: Emergency Education Public Appeals................... 21 Key Links to Share with Colleagues ............................................................................... 24 Background: Teachers Without Borders and Education in Emergencies ....................... 24 Course Overview The news about large-scale emergencies is inescapable and all-too familiar. ASAP: Education in Emergencies was designed to help the public explore the complex issues of education in emergencies. We will explore “national” and “natural” disasters, as well as the space in between, and evaluate the relationship between education, international development, and global aid. The Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) shall serve as our guide. This course is devoted to — and is based upon —the work of the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE). It is this instructor’s opinion that INEE represents our greatest hope for children and the capacity for educators to ensure their safe future. This course will cover (1) a review of basic elements surrounding the vast field of education in emergencies (2) the work of INEE, along with examples of INEE’s Toolkit in action (3) an exploration of a case study designed by practitioners, global agencies, and stakeholders, and (3) how the global community of development personnel, aid workers, and donors intersect with education in emergencies. The subject of education in emergencies is not for the faint of heart. Most likely, this course will challenge, exasperate, anger, and raise more questions than provide answers. For example, many claim that it is near impossible for schools to function adequately or establish any semblance of normalcy. NGOs, well-resourced individuals, and global agencies attempt to address these gaps, but some states have been known to rely on foreign aid rather take on the chief responsibility of protecting and educating their people. In an alarming number of cases, schools have served as havens for criminals, warehouses for arms, and targets of attack. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 2 More specifically, let’s say that an earthquake has just struck a seismically vulnerable country. Thousands are crushed by their homes. In many under-resourced, densely populated communities living atop shallow fault lines, close to 50% of the children who die in these earthquakes perish in their schools. When is a “natural” disaster a truly preventable “national” disaster? How have poor or unenforced building codes and policies, a lack of transparency, wholesale neglect, misinformation, or a lack of preparedness and planning contributed to the catastrophe? Have the tyrannies of the urgent plaguing that country made it such that disaster risk reduction is unaffordable or a secondary priority? On the positive side, how have countries prepared themselves and their people to address these crises? What can we learn from them? Are their practices portable, replicable, and sustainable? We hope you will raise several such questions. I hope we can all agree on this: in emergencies, children are especially vulnerable to the ravages of human trafficking, disease, and recruitment into paramilitary gangs. At the onset of a crisis, human necessities must be addressed ASAP, triage style: stop the bleeding; protect, feed, clothe, and house the people; seek more aid; rinse and repeat. One may assume that education in emergencies is less urgent. This is where the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) comes in. About the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies INEE has pioneered the notion that education is a basic necessity and cannot wait, and that education is an indispensible and parallel component of relief. Even more, INEE stresses the importance of prevention and planning, as well as coordinating and connecting those working in response, recovery, and reconstruction. INEE gathers and supports global stakeholders to build and maintain Minimum Standards for Education in Emergencies. Thanks to INEE, educators are now part of first-responder teams. Education clusters coordinate activities, assess needs, accelerate normalcy, and make it possible for other emergency work to continue. INEE has made it clear that education is the currency that drives communities and simply cannot be separated, sheltered, or subsumed during an emergency. In short, INEE is an extraordinary example of collaboration. Collaboration is essential in this course as well. We shall emphasize learning from and with one’s new online colleagues and with organizations working in the field. Finally, I cannot stress this enough: this course is an introduction to the field of education in emergencies, not a comprehensive training program. It is impossible to do justice to these issues in a single course. All emergencies do not look, feel, or act alike, requiring a complex interplay of culture, history, power, language, local assets, global resources, obstacles, and opportunities. Expertise in the field of education in emergencies requires in-depth training, mentorship, and professional development – impossible to achieve in the short time we have together. But you have to start somewhere, and I say we must do so ASAP. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 3 Credits and Grading Criteria CREDITS: This non-credit course professional development course is available for Continuing Education Units (CEUs). To receive CEU credit, all assignments must be completed. The professor may require that students make edits before determining the completion of any assignment. In addition to the written assignments, students are required to respond to the readings and to each other throughout each week by posing or responding to issues or comments. This cannot be saved up until the end. Should there be any issue about making deadlines, please contact me in advance. “Attendance” is determined by student engagement with the classroom content and tools, with other students, and with the instructor. GRADING: We’re going to be using a point system. You’ll get feedback on discussions and assignments. Please know that your work will NOT be judged based upon the style or grammar of your writing, especially because a significant number of colleagues will not be writing in your first language. That would not be fair. Students’ submissions for assignments shall be evaluated based upon the following criteria: [6]: Exemplary: Clear incorporation of research, an extra effort to learn more, proper acknowledgment of material other than your own, creativity, and clarity. All of this would be worthy of sharing to educators around the world and makes a contribution to our knowledge of teaching and learning. Mentor status. [4-5]: Meets Requirements: Satisfies the expectations of the assignment with professional use of sources. Core competency [3]: Needs Work: Basic treatment of the ideas, but needs to dig deeper in order to show core competence. To get credit, I would be asking for a revision [0-2]: No Credit: (a) Student uses others’ ideas as her/his own without attribution, and/or (b) does not address or respect the assignment. Technology and Public Blog Posting Requirements You will need to get technologically organized so that you can know where to go for information and what to do to access required technologies. Once I receive your email address from the registration office at Johns Hopkins University School of Education, I will send more information about these required technologies, including invitations to various sites you’ll need to access (or form accounts on) so that you can meet course requirements. Course Platform (ELC): This is where you will go to access course content, get assignments, hold discussions, and receive comments/grades on papers. Blog (Required). All students are required to have a blog so that your writing can be made available and accessible publicly. You can use any blog service that you like: WordPress. Blogger, Tumblr are all good examples. If you’re new to blogging, there are plenty of great tutorials and great advice to help you get started. Each assignment description will clarify whether to post it to your blog as well as to the ELC Gradebook. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 4 Essential Course Policies Policies on Sharing Intellectual Property The Internet represents a new, intellectual social contract. Today, learning requires the sharing of ideas, but it must be done honorably. You might write something that someone, somewhere needs. Post it and share it.1 You might also find the perfect article to address an issue you wish to explore for an assignment. Go ahead, post it, but you must cite it and give credit to the author — direct us to the URL so that we can all benefit. The assignments are not roadblocks to conquer, but opportunities for growth. An article you may have just found is a means, not an end, to a point you want to make. Use it to reinforce your point, not in place of your point. Plagiarism (copying and pasting the work of others without appropriate attribution or credit to the author) is theft, plain and simple. Plagiarism: Your Reputation is at Stake On occasion, I will spot-check for plagiarism, but I don’t want to chase after you. That’s not learning — it’s policing. At the same time, your blog posts will be public. If you copy and paste others’ work without proper attribution, someone will notice. Your reputation, even your job, could be at stake. As U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously observed, “sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants.”2 Your reputation should be the driving motivator for doing one’s best in this course. Official Language from Johns Hopkins University on Academic Integrity “Violations of academic integrity and ethical conduct include, but are not limited to, cheating, plagiarism, unapproved multiple submissions, knowingly furnishing false or incomplete information to any agent of the University for inclusion in academic records…” For full policy and misconduct proceedings, see the Academic Policy section of School of Education. Late Work Policy Educators are some of the busiest people in the world. I understand how the tyranny of the urgent can play havoc with deadlines. At the same time, many assignments require collaboration, and group work entails obligations to each other. Whether it is an individual assignment or a collaborative project, please be reasonable, and I will be as well. Whatever the circumstance, please inform me (and others you may be working with) so that no one is caught off guard. Excessive lateness could result in notification of no-credit for the assignment and/or the course. Religious Observance Accommodation Policy While this is an online course, religious holidays are valid reasons for exceptions to deadlines. I simply ask that you let me know as early in the term as possible in order to ensure there is adequate time to make up and respond to the work. 1 The majority of our policies about the creation, use, and reuse of content are adapted from the work of our colleague, David Wiley, PhD of Brigham Young University — a pioneer in the field of Open Educational Resources (OER). To learn more about the transformative power of OER, please look up: www.davidwiley.org and, in particular, his course: Introduction to Openness in Education. 2 Louis D. Brandeis, cited on the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville website, in Other People’s Money – Chapter V: http://bit.ly/9vfrYh ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 5 Participation Participation and discussions are included in student grading and evaluation. The instructor will clearly communicate expectations and grading policy in the course syllabus. Students who are unable to participate in the online sessions for personal, professional, religious, or other reasons are encouraged to contact me to discuss alternatives. Statement of Academic Continuity For any of us, things happen. In the event of issues (serious personal matters, no access to the internet, or other extraordinary circumstances) preventing active participation in, and/or the delivery of this online course, we’ll do our best to make accommodations. If it happens to your course instructors or the School of Education’s platform goes down, for example, we may have to change the normal academic schedule and/or make appropriate changes to course structure, format, and delivery. Accommodations for Students with Disabilities If you are a student with a documented disability who requires an academic adjustment, auxiliary aid or other similar accommodations, please contact the Disability Services Office at 410-516-9734 or via email at soe.disabilityservices@jhu.edu. Statement of Diversity and Inclusion Johns Hopkins University is a community committed to sharing values of diversity and inclusion in order to achieve and sustain excellence. We believe excellence is best promoted by being a diverse group of students, faculty, and staff who are committed to creating a climate of mutual respect that is supportive of one another’s success. Through its curricula and clinical experiences, the School of Education purposefully supports the University’s goal of diversity, and, in particular, works toward an ultimate outcome of best serving the needs of all students and the community members. All of us (faculty, mentors, organizations, students) are expected to demonstrate a commitment to diversity as a measure of our mutual strength. Course Readings and Media There are no required textbooks or materials. All readings have been selected from available sources freely available on the Internet and are listed here in the syllabus. Online Public Events/Webinars: Conversations with Colleagues This course will likely include students from around the globe. We all share a passion for the subject, but will rarely share the same time zone. Therefore, my courses stay away from bandwidth-heavy, real-time teaching and focus. Instead, they focus on individual scholarship, local action, and group collaboration. Nevertheless, I still do miss live discussions, so we’re going to attempt some here and do our best to offer them during reasonable hours. We will record these webinar-like conversations, of course, should you not be able to participate. We will provide you with all the technology you’ll need to participate. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 6 Public Conversation/Webinar: (Dates TBD) “Global Tragedies: Local and Global Solutions” A short presentation a seasoned professional in the field, followed by a conversation. For example, I am presently discussing a date for such a webinar with my colleague, Sharon Ravitch, PhD, a professor of Education at the University of Pennsylvania and the Senior Advisor to the Minister of Education of Haiti. I hope Sharon will be able to join us to address the challenges and opportunities of working in Port- au-Prince following the 2010 Earthquake, along with her particular contributions in community assessment and countrywide educational capacity building. There will be plenty of time for questions and conversation. Public Conversation/Webinar: (Dates TBD) “Humanitarianism Without Humanitarians?” The title of this webinar examines a reading from the digital activist, Patrick Meier, PhD., a pioneer in the role of technology and emergency relief, global transparency, and mapping in crises. His blog is worth reading: http://irevolution.net/. I will do my best to attract Patrick to participate in this week’s session and webinar. Public Conversation/Webinar: (Dates TBD): “Earthquakes, Floods, and Education: A Conversation with Colleagues in Pakistan and Tajikistan” I am arranging short presentation by Teachers Without Borders colleagues: (1) Sameena Nazir, Founder of PODA (Potohar Organization of Development Assistance), an NGO devoted to the education of girls, crafts, and human rights in Pakistan, and (2) Solmaz Mohadjer, Founder of PARSQUAKE (an organization for earthquake education in the Persian-speaking community). Here, too, we’ll follow the presentations with ample time for questions and comments. MODULES Getting Organized | Getting Acquainted Session 1 Getting Organized Once you are enrolled, you’ll receive instructions on how to access course Please sign up for a blog and fill out the Google Doc with the name and URL. For more information, please see our Technology and Blog Posting Requirements, as well as course policies, which include specifics about intellectual property Please fill out the survey Discussion #1: A Response to a Poem Most online courses ask students to introduce themselves. Fair enough. I often take a less direct approach by asking variations of this provocative question: “What do you see outside your window, and how does this shape your view of education today?” Sometimes I ask for a personal response to an image, or a short video to represent the window metaphor. This time, however, I want to take a different response. Please respond to a poem by Nobel Prize winner, Wisława Szymborska, entitled “Psalm.” ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 7 I have not chosen her poem to elicit a conversation about religion (as its title may connote), but rather to ask you to describe your interpretation of, and thoughts about, the poem in light of what might lie ahead in a course about education in emergencies. It’s best to let the poem percolate by sitting quietly after you read it, rather than rushing to the keyboard. Structure: Please include your name in the title of your post. Ex: Fred Mednick: Borderless Conflicts When you read this, what does your heart or your head bring forth? Quote lines. Please also comment on at least two other colleague’s posts. Central Questions3 1. How would you define the field of “education in emergencies”? 2. Why has education been left out of standard humanitarian response until recently? 3. What is an educational intervention? 4. What are the international legal foundations, obstacles, and challenges that underpin education in emergencies? 5. How might the growing awareness surrounding the needs of children in emergencies (establishing “normalcy,” “child protection,” and “psychosocial well-being”) affect the strategy of humanitarian response? 6. What role might culture, religion, and class play in emergency education? 7. Who and what are the key players, structures and institutions for education in emergencies and how do they work together? 8. What are the reliable methods for evaluating the impact of education in emergencies? Readings Multiple Faces of Education in Conflict-Affected and Fragile Contexts: Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) Working Group on Education and Fragility Education Under Attack: UNESCO Schools as Battlegrounds: Human Rights Watch Discussion #2: Response to Central Questions Read the Central Questions again, then choose one that inspires to pursue? Your choice might reflect personal experience. If, indeed, you experienced any of the issues presented personally, you may use that as a powerful way of contextualizing your choice. If it’s too early to open up (the issue may be too raw), please do not feel compelled to do so. You may, instead, choose to These questions are derived from Teachers Without Borders’ experience in the field and from the excellent syllabi posted on the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies website’s Academic Space. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without 8 Borders 3 focus on what you’ve learned, what you noticed, what you believe is missing, what you would like to pursue. Please also comment on at least two responses to your colleagues. The Wrong Place at the Right Time: Introducing INEE Session 2 Overview “The Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) is a global network of individual and organizational members (as of June 2006) who are working together within a humanitarian and development framework to ensure the right to education in emergencies and post-crisis reconstruction. INEE works to improve communication and coordination by cultivating and facilitating collaboration and constructive relationships among its members and partners. The INEE Steering Group provides overall leadership and direction for the network; current Steering Group members include CARE, Christian Children’s Fund, the International Rescue Committee, the International Save the Children Alliance, the Norwegian Refugee Council, UNESCO, UNHCR, UNICEF and the World Bank. INEE’s Working Group on Minimum Standards facilitates the global implementation of the INEE Minimum Standards for Education in Emergencies, Chronic Crises and Early Reconstruction.”4 Objectives To explore issues faced by those working in the Education in Emergencies field To recognize and articulate the structure of INEE and apply principles to case studies and further activities/exercises To enable students to demonstrate how educational systems prepare for and react to various sorts of emergencies, from the general sense that educational systems themselves are in crisis to natural disasters such as earthquakes to manmade disasters such as wars Readings 4 Education and Emergencies: Humanitarian Coalition INEE: Minimum Standards: Preparedness, Response, Recovery: INEE Protecting Education: media clips Education Strategy 2012-2016 and UNHCR Where We Work: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees The Sphere Project: The Humanitarian Charter Frequently Asked Questions about INEE and the INEE Minimum Standards | http://bit.ly/1bfYKkK ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 9 Learning is Their Future: Darfuri Refugees in Eastern Chad: INEE and Sphere Project (to serve as a model for the assignment) It is impossible to digest these hefty readings in such a short time. The intention here is to give you a sense of the enormity of the subjects faced by researchers, networks, and practitioners working on education in emergencies. As we continue with the course, I am certain you will return to these documents and to consult the networks and resources to which they refer. Activity The UNHCR report (see link to “Education Strategy 2012-2016,” above) identifies 13 priority focus countries: Bangladesh, Chad, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Kenya, Malaysia, Pakistan, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Uganda and Yemen. On page 12, please read the UNHCR criteria for their choice of priority focus countries, each of which will be supported in “developing multi-year, multi-sectoral education strategies based on the local context and existing education programmes.” (Unfortunately, the link to the country fact sheets is restricted to UNHCR staff) For now, we shall focus on the crisis of Darfuri refugees in Eastern Chad to illustrate how the INEE Minimum Standards can guide strategic planning, policy, and programs.5 Special appreciation is in order for Ariana Sloat for her design of a Case Study (from which our activities are drawn). Ms. Sloat is Deputy Coordinator for Minimum Standards and Network Tools. What follows is a self-paced module to be pursued in the following order, beginning with an Overview and ending with Feedback. To truly absorb the depth of the issue, it is essential to make the effort to read the documents to which it refers. Overview Foundational Standards Access and Learning Environment Teaching and Learning Teachers and Other Educational Personnel Education Policy Conclusion Resources and Acknowledgments Feedback You can click inside the circle (on each of the pages you see to the left) for more information. Discussion: Share your feedback (last item on the Activity list) with your colleagues by posting it as a discussion topic. TBA: Public Conversation/Webinar 1: “Global Tragedies: Local and Global Solutions” A short presentation by Sharon Ravitch, PhD, a professor at the School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania and the Senior Advisor to the Minister of Education of Haiti. Sharon will address the challenges and opportunities of working in Port- au-Prince following the 2010 5 Special appreciation and acknowledgments are in order for Ariana Sloat, Deputy Coordinator for Minimum Standards and Network Tools: arianna@ineesite.org ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 10 Earthquake, along with her particular contributions in community assessment and countrywide educational capacity building. There will be plenty of time for questions and conversation. If Only: Gaps and Connections Between International Development and Global Aid Session 3 Overview We began this course by diving right in and looking at the gravity of education in emergencies. I’d like to pull back the lens even further in order to evaluate how the field fits into the overall global development agenda and to identify areas of study, particularly now that the post Millennium Development Goal era quickly approaches. All of this is intended to deepen one’s understanding of the connections, best practices, and gaps in the space between development and global aid, with a particular emphasis on how INEE seeks to bridge the gap. The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were conceived at the Millennium Summit in September 2000 after world leaders in history adopted the UN Millennium Declaration outlining a set of 8 goals, with particular targets for 2015. These 8 MDGs address issues of “poverty, hunger, disease, lack of adequate shelter, and exclusion-while promoting gender equality, education, and environmental sustainability. They are also basic human rights-the rights of each person on the planet to health, education, shelter, and security.”6 According to the United Nations, the eight Millennium Development Goals “…form a blueprint agreed to by all the world’s countries and all the world’s leading development institutions. They have galvanized unprecedented efforts to meet the needs of the world’s poorest.” Access to high-quality education is widely recognized as a universal human right. MDGs focus on national self-reliance, sound policy, sustainability, educational access, and global transparency. It’s an optimistic vision and proponents do make a compelling case — more children than ever are attending school; MOOCs (massive open online courses) are not only free, but inclusive, watchdog agencies are exposing abuses. While global diseases have become more difficult to identify and treat, public health successes in areas such as hygiene and immunization campaigns have benefited from public-private partnerships and individual philanthropy (Bono, Gates). The picture of development through education is not altogether rosy. In many poor countries, a quality basic education is hardly universal. And the voice of those critical of development and aid are growing louder. The firestorm of criticism directed toward the development world is particularly scorching. If, as H.G. Wells once said, "education is a race between civilization and catastrophe," then many claim catastrophe is winning. More sub-Saharan Africans have cellphones than access to clean drinking water. Poverty pornographers descended upon Haiti after the earthquake in order to raise money, yet today, three years later, there is enough rubble in the streets of Port-au-Prince streets to build a four-lane highway to Los Angeles and back again. 6 U.N. Millennium Project: http://undevelopmentproject.org ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 11 Bookshelves are filled with this topic, and their titles speak volumes: The Road to Hell: Ravaging Effects of Foreign Aid and International Charity;” “The Lords of Poverty: The Power, Prestige, and Corruption of the International Aid Business;” “White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done so Much Ill and so Little Good;” “Famine Crimes: Politics and the Disaster Relief Industry in Africa;” “Condemned to Repeat?: The Paradox of Humanitarian Action;” “The Crisis Caravan: What’s Wrong with International Aid?” Depressing, indeed. Palagunmi Sainath’s Everybody Loves a Good Drought; Stories from India’s Poorest Districts paints a nightmarish, “development-is-its-own-disaster” picture of dogooders: “Development is the strategy of evasion. When you can’t give people land reform, give them hybrid cows. When you can’t send children to school, try non-formal education. When you can’t provide basic health to people, talk of health insurance. Can’t give them jobs? Not to worry, just redefine the words “employment opportunities." Don’t want to do away with using children as a form of slave labor? Never mind. Talk of ‘improving the conditions of child labor!’ It sounds good. You can even make money out of it.”7 The key takeaway is for you to decide. In the meantime, many would agree that we must bridge the gap between international development strategies and the world of global aid following a disaster. It’s akin to the adage that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound a cure. If only, many say. This is a key opportunity to think about the connection between development and aid, about integrating these perspectives into teaching practice, whether in our own backyard or around the world. It is particularly important here to review the INEE Toolkit and other INEE documents to learn more about the strategy of mobilizing networks of high-quality development and humanitarian organizations and agencies. Readings and Review Millennium Development Goals: (United Nations) MDG Monitor: Tracking the MDGs: (Global Governance Watch) One: powerful infographics about the Millennium Development Goals Education in Emergencies - Critical Factor in Achieving the MDGs: (International Rescue Committee) Discussion Post Whether you are unfamiliar with the MDGs, a well-seasoned practitioner in the trenches, a head of an NGO, or a donor, what would you do to affect one of the MDGs in an area of education in emergencies? Why? How? Would you work in the policy area for maternal-child health? Associate yourself with a particular NGO in a region you know about or you know is suffering? Although it may be hard to contain yourself, do not focus on what has been done poorly by others, but what you can see yourself doing. NOTE: We’ll form working groups to connect a particular MDG with a particular emergency and a toolkit used in the field 7 Sainath, P. (1996). Everybody loves a good drought; stories from India’s poorest districts. Penguin Books., p. 421 ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 12 Drilling Down, Digging Out, Delivering Education: The INEE Toolkit Sessions 4-6 Objective: Purpose, Groups, and Project These next three sessions are meaty and complex. I have provided a great deal of detail for each step of the way, so reading this syllabus carefully is absolutely essential. These sessions involve lots of communication in a global collaboration within groups formed around each of the Millennium Development Goals (2) The production a 1.5 page briefing paper and group slide show, available to the public, to connect the MDG you have chosen with an emergency in a particular region. We will: Dig deeper into the MDGs and work with a group based upon one you choose Collaborate on a project within your MDG group Review research and activities that address your MDG in a particular country Choose an acute or protracted emergency taking place in that country Identify and interview practitioners working on that emergency Make connections between Millennium Development Goals and INEE thematic areas Create the briefing paper and assemble the public, online slide presentation based upon what you have learned Even more, it takes place in the middle of the class, rather than as a culminating assignment. I know this all sounds a bit crazy, but there is a method to the madness. If you train yourself to think big picture, even amidst acute or protracted emergency, you’ll be better off. In the world of development, if one digs in the trenches only, one cannot see where it’s going. If one flies overhead, one cannot even recognize the trench. This is about leadership and about the complex relationship between compass and map, development and aid. Besides, this work always requires that one bite off more than one can chew. Patience required. Hopefully, three weeks will be enough time to accomplish it all. Overview A high-ranking United Nations section leader once gave me a working definition of a teacher: “From my experience in the field, a teacher is anyone with valuable information to share.” It is interesting to note that, whether you are a student envisioning your future, a seasoned professional, or a donor, you’re an educator. Even more, relief agencies have made the mistake of not conducting an assessment of community assets, alongside of their characteristic deficit assessments. Should that be standard practice (again, part of INEE protocols), services not only can be enhanced, but also sustained. Doctors and community health workers can be refugees, too, with many of the same intellectual resources and more credibility than those flown in. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 13 This session is designed to introduce you to well-crafted handbooks developed by INEE and partners, in very close communication with community leaders. It is now time to start drawing threads together: your passion, the MDGs, and now the INEE Toolkit, by choosing a thematic area you would like to discuss further, in groups. Focus on the INEE Toolkit Thematic Issues. Keep in mind your passion for a particular issue the earlier readings (INEE, Education Under Attack, the Millennium Development Goals), and our class discussions. All of this will lead to joining ONE MDG group, discussing your views there, and preparing a project presentation that will connect MDGs and INEE Toolkit Thematic Areas. Think of it this way: One Column is an MDG; another column is an INEE Thematic Theme. Your job is to draw vital connections between them. STEP 1: Required Readings INEE Toolkit Key Thematic Issues/Resource Packs (required: centerpiece for what follows) INEE Standards Integrated Toolkit: Integrated Humanitarian Response (support document) Millennium Development Goals (website) Recommended Readings Education in Emergencies: Toolkit - Prevention Web (worth scanning) Disaster Risk Reduction: UNICEF – South Asia (for your reference) Millennium Development Goals (individual pages) Eradicating extreme poverty and hunger Achieving universal primary education Promoting gender equality and empowering women Reducing child mortality rates Improving maternal health Combating HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases Ensuring environmental sustainability Developing a global partnership for development STEP 2: Join and Work in a Millennium Development Goal (MDG) Group After you’ve done some reading, join a group that reflects your interest. Choose wisely, as this will be a working group for the next three weeks. Instructions for Joining an MDG Group: (to be provided) 2a: Post to the Discussion Space in your MDG Group Post a reflection to the discussion (personally or professionally) about why you have chosen this group. Describe the thematic area you have chosen as well. Is it something you are simply curious about or that strikes you as entirely new? Is it a personal or professional experience that drives you to learn more or to express yourself? Are you suspicious about, or inspired by, current efforts in this area? ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 14 2b: Inside Your Group: Get Organized Here is where the moving parts start kicking in, so being organized really matters. The group space on the Hopkins courseware site includes these components: Updates, News/Blog, Discussion, Chat, Resources, and a Calendar. Make certain you use the Resource tab for listing your organizations and contacts used in your research. (We’ll download everyone’s resources at the end of the course and make certain that all have a copy). This should be enough to keep you organized. If not, you can communicate via email, Google Groups, or whatever the “organizers” amongst you feel is best. Your group will depend upon each person’s effort in order to accomplish the following: To learn more about your chosen MDG To choose an acute or protracted emergency and learn more about it To discover the players working on your chosen MDG and chosen emergency To share interviews with those players To investigate how the INEE Toolkit is being used (or can be used) there To create a briefing paper (1.5 pages) and public slide presentation ADVICE ABOUT GROUPS: Groups can be really frustrating because of lack of communication or clarity. After you have introduced yourselves, talk frankly about protocols. I’ll post more links to guidelines for group-work to help you along the way. In the meantime, here’s what I have learned over the years: in groups, some colleagues emerge as leaders, while others like to play a supporting role. Some wish to focus on numbers; others on stories. Many groups take on these roles: Organizers: People valued for their ability to manage Creators: People who create content (numbers, stories, and pictures) Distillers: People who transform complex ideas into forms we can all understand Presenters: People who put it all together for public presentation Technologists: People who get technology and can solve problems for everyone STEP 3: Group Decision: A Particular Emergency and Research Your MDG group needs to choose either a (1) recent or acute emergency this or last year, like ethnic cleansing in Burma, or (2) an ongoing emergency, like the protracted reconstruction efforts in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake. So, at this point, you’ve gathered as an MDG group and now you’re deciding on WHAT emergency and WHERE. Explore BOTH the MDG and the emergency in that country. Keep in mind that your group presentation will focus on the questions raised at the beginning of this course. What types of interventions are happening to address the emergency? Who are the key players, structures and institutions? How do they work together? How has the INEE Toolkit (and others like it) been used to address the issue? What are the challenges? (Examples: government obstruction, lack of resources, corruption) How might the growing awareness surrounding the needs of this emergency affect the strategy of humanitarian response? What role might culture, religion, and class play in this emergency? ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 15 What methods are being used to evaluate the impact of education in this emergency? Look at research, data sets, media reports, voices from the field, blogs, images, video, and watchdog networks. In short, what is going on? Think about this from the development perspective (MDGs) and the emergency perspective (INEE: relief and aid). On the next page, please find a chart that can give you a more visual sense of what I would like you to do. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 16 CHART: Matching the MDG with the INEE Thematic Area/Toolkit – At a Glance MDGs INEE Toolkit Conflict Mitigatio n Disaster Risk Reduction Early Childhood Gende r HIVAIDS Human Rights Inclusive Education Protectio n Psychosoci al Support Youth MDG 1: Eradicate Extreme Poverty & Hunger MDG 2: Achieve Universal Primary Education MDG 3: Gender Equality, Empowerment MDG 4: Reduce Child Mortality Rates MDG 5: Improve Maternal Health MDG 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, Malaria MDG 7: Ensure Environmental Sustainability MDG 8: Develop Global Partnerships for Dev. Let’s say that you have chosen MDG 3: Gender Equality, Empowerment. Now you have a group devoted to the issue. Next, your group debates the various INEE Toolkits and decides to focus on Human Rights. Next, someone suggests places to go for research. Another person learns that there is an extraordinary NGO, Potohar Organization for Development Advocacy (PODA), in Rawalpindi, Pakistan that focuses on gender equality and empowerment through training in education and human rights. They have been working on this issue for quite some time, and have become increasingly vocal about Pakistan’s status on scales measuring progress toward the MDGs. You’d clearly place them on the development, versus aid and relief side. They educate girls, gain support from men for women’s empowerment, teach crafts, and every room displays a poster of the UN Declaration of Human Rights. Lately, however, they have stepped up their efforts to identify the issue as an emergency, especially in light of the news about how a girl, Malala Yousafzai, was shot for promoting education for girls. The head of that organization, Sameena Nazir, is available for a Skype or email interview. Others choose to interview field workers at international agencies or NGOs. At this point, you’re in great shape: ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 17 You’ve chosen an MDG, an INEE Thematic Area, and a region where an ongoing emergency is taking place. Next, interviews. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 18 STEP 4: Individual Interviews EACH member of the group needs to: (1) identify an organization working in the field, and (2) interview someone there who has had direct experience with the emergency. (2 pages, maximum). Your best sources will come from INEE and other websites you’ve come across thus far. Find someone there to interview for a maximum of 45 minutes to gain the perspective of someone working in the field. Interview Approach/Tone: Introduce yourself and this course. Reassure the interviewee that you’re not collecting evaluative data, but rather simply gathering insights; the tone of the interview should be informational and appreciative. That’s why I decided not to script the questions for you; what matters most is your interaction and experience of learning from and with those in the field. You might ask about her/his motivations for tackling this issue (whether or not s/he associates it with a particular MDG). You might follow that up with questions about activities and programs, challenges, successes, setbacks, and surprises. Your conversation may lead to issues about funding, leadership, coordination, community outreach, or their experience with evaluation. If possible, ask her/him to tell you a story. For instance, you might ask: “Ten years from now, what image or experience do you think will stand out for you?” Although somewhat clinical, here’s a UN questionnaire conducted by the Special Reapporteur of the U.N., addressed to NGOs, regarding human rights 4a. Post your full interview on your blog. Please include the name of the organization and its website 4b. Write a one-paragraph summary for your group discussion space. Your group will be consulting these in order to highlight three for the online, public presentation STEP 5: Create a Group 2-page Briefing Report. The audience for such a report is a high-ranking UN official. Add a list of references (websites), substantiating your claims, to the 1.5-page Briefing Report. Here’s what you need to do: Title Page: Include the name of the MDG and a descriptive subtitle, such as Advancing MDG 3: Gender Equality and Empowerment — Employing the INEE Toolkit in Pakistan. List each team member, along with a few words about each person’s contribution. You’ll see how the online public presentation (coming up) will reflect these categories. One Page: Describe the nature of the emergency as objectively as possible. Establish your credibility with the facts. If news reports conflict, note that. Though it will be hard to do, avoid making recommendations. Just make your case for the emergency itself. Second Page: Hardly comprehensive, make a concise case for taking one specific action, such as launching an official United Nations public campaign; initiating a resolution or policy discussion. This is where your earlier research on MDGs and actors in the emergency you’ve chosen can be distilled and made available to STEP 6: Create an online slideshow about your work. I have created an online Google Presentation template (which you can copy to customize for your own group) ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 19 1. Here’s a link to a template for your slideshow: http://bit.ly/12nN7Ev. It is a Google Presentation application, so someone in the group needs to have a Google account. 2. Rename the Google Presentation with the same title as your Briefing Paper. Example: MDG 3: Gender Equality and Empowerment — Employing the INEE Toolkit in Pakistan. If you all have a Google account, then you’re in business. If only some of you do, I suggest that one member of your group should make it available to other by downloading the renamed version to PowerPoint or PDF and share it. Somehow, as it goes through revisions within your group, you’ll need to stay in touch about the latest versions. JUST ONE LAST STEP! Super Important Requirement: Sharing Once you have completed your Briefing Paper and Google Presentation, all you need to do is share it with the world. Here’s how: Everyone should POST A COPY of the Briefing Paper to your individual blogs. After all, you collaborated on this and you are all authors ADD THE WEBSITE OF YOUR GOOGLE PRESENTATION to the bottom of your briefing paper You did it! This was a huge undertaking. Congratulations! NOTE: Depending upon the size and vitality of the groups, this is where we’ll decide whether to create new groups (for discussions) or reconvene for discussions with all colleagues taking this course Momaland: Case Study and Assessment Strategies Session 7 Overview Thanks to INEE and its network, there are excellent and actionable models for assessment: technical briefs; disaster-specific summary sheets, checklists, and best practices; quick impact analyses; instructions for determining needs for child-friendly spaces; qualitative and quantitative research techniques; mobile phone data-gathering applications; how-to videos; joint and coordinated assessment matrices; and much more. Between INEE’s Monitoring and Evaluation manuals and those of The Assessment Capabilities Project (ACAPS), you’ll have all the invaluable resources one would need. One of the best ways to understand these assessment resources is to dive into a fictional, yet realistic, case study. Momaland: Education Following an Emergency was developed by UNICEF, INEE, and Save the Children (with a great deal of input from field workers) to support concentrated or extended trainings that provide a likely scenario requiring attention to the multiple, intersecting components and complexities of education in emergencies. Momaland can help us learn more about the various components of assessment and evaluation for education in emergencies. The readings include a slide-deck offered in ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 20 trainings, along with a comprehensive Facilitator’s Guide (worth reviewing) that incorporates much of what we’ve studied, thus far. Both are included in the readings. The Facilitator’s Guide, even just the Momaland session, can compris an entire course. Even so, just a cursory reading will reveal how the INEE Minimum Standards and other protocols play themselves out, and how essential they are. Reading Momaland: Slides Education in Emergencies Training: Facilitator’s Guide (INEE, UNICEF, Save the Children). Pay close attention to Session 6. Additional Reference Material (For Your Files) More INEE Case Studies: Afghanistan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Cambodia, and Liberia, as well as a Synthesis Report Real Time Evaluation of Humanitarian Action (Bibliography) Assessment and Evaluation: documents curated by Teachers Without Borders Discussions (Suggestions below) What stands out? What do you wish this course had addressed? How might such a training program affect your career path, knowing that you might face a scenario very much like this one? Conduct an additional search to determine who has used the program and how. I am asking you to think about your original motivation for taking the course and what you’ve learned so far, mixed in with a picture of what things might look like for you. Support from Viewers Like You: Emergency Education Public Appeals Session 8 Overview Girl Rising, a new film highlighting the extraordinary stories of 9 girls and 9 issues they face, worldwide, has drawn much-needed attention to the subject of girls education. Films like Girl Rising and the Internet put the world of images, data, and compelling news in our pockets. Movie stars, billionaires, and citizen journalists have entered the picture, too. Tweets from Tahir Square flash across our screens, along with YouTube postings direct from Homs, Syria. Appeal apps enable micro-donations via text. Unfortunately, the ubiquity of “disaster du jour” appeals can lead to donor fatigue. Tragically, despite a dramatic increase in the visibility of appeals for assistance for emergencies, funding by governments remains stagnant. According to INEE, only 2% of funds in humanitarian aid goes to education. Here, too, INEE and partners have also developed extensive communication protocols and best practices for successful appeals. The appeal process involves a complicated supply ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 21 chain of transparency, communication, impact analysis, and accountability. This course does not all us the time to give the appeal process the attention it deserves. Again, the INEE site’s resources are specific, clear, and essential for anyone in the position to coordinate this process. I have listed several INEE resources in this syllabus. For now, I am asking only that you familiarize yourselves with these protocols in order to post a discussion topic and to participate in an upcoming Online Public Conversation /Webinar. Discussion A couple of choices here (a few paragraphs, plus please comment on others’ posts) 1. Point to a specific disaster (within the last three years) for which a successful appeal was made. What made it so? A concise paragraph with a list of your references is all that’s needed 2. Please identify a failed public appeal for support following a disaster (within the last three years) due to the following: Not enough money or resources could be raised to make a difference So much money and resources were raised, that they could not be deployed There was no capacity for receiving, distributing, or securing relief, resulting in a coordination disaster Coordination was mishandled or missing entirely Here’s some advice for those who wish to discuss the second option: there is a growing genre of books about failed development projects. Try to avoid these, especially after just having explored so many tragic issues. Just focus on the mechanics or the missing elements of the appeal process. An earthquake has taken place or a civil disturbance has broken out. Clearly, communities have been devastated or are in danger. What happened…or didn’t happen? Reading to Prepare for Public Conversation/Webinar Does the Humanitarian Industry Have a Future in The Digital Age?: (required) Ushahidi: plus crowdmapping tool available for public use: www.crowdmap.com Education First’s Education Can’t Wait INEE: Promotion and Advocacy Online Public Conversation/Webinar 2: “Humanitarianism Without Humanitarians?” (Date TBD) The title of this public conversation/webinar was coined in this week’s reading by digital activist, Patrick Meier, PhD., a pioneer in the role technology plays in emergency relief, global transparency, and mapping in crises. His blog is worth reading: http://irevolution.net/. I will do my best to attract Patrick to participate in this week’s session and webinar. We hope to discuss diverse points of view on the subject of the impact of individual efforts and the technology-enabled wisdom of crowds in disaster relief. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 22 ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 23 Key Links to Share with Colleagues Education Under Attack Schools as Battlegrounds: Human Rights Watch The Sphere Project Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies INEE: Minimum Standards English INEE Toolkit UNICEF: Education in Emergencies: A Resource Toolkit Emergency Education for Children Education and Conflict Mitigation Education Protection Annotated Bibliography: Teacher Professional Development in Crisis This is a small fraction of the links to organizations, networks, documents, news, and resources. Please join INEE and search their website for a far more complete list Background: Teachers Without Borders and Education in Emergencies In 2000, Teachers Without Borders (TWB) was launched in order to connect teachers to information and each other in order to help local leaders make a difference in their local communities—on a global scale. At 59 million, teachers represent the largest professionally trained group in the world—the catalysts of change and the glue that holds society together. They know who is sick, missing, or orphaned by AIDS. Yet teacher professional development is often irrelevant, spotty, or missing entirely—compounded by ill conceived or poorly implemented policies, a precarious world economy, and both national and natural disasters. Teachers Without Borders did not enter the field of teacher professional development with the idea that we would be involved in Education in Emergencies, but—upon reflection—EiE has been what we’ve been about all along. Our first project took place in a Bedouin village within the Occupied Territories. Subsequent projects gathered teachers from regions in conflict (Rwanda, Nigeria, Pakistan, Afghanistan) to discuss teaching and learning, despite the obstacles of civil unrest and we assisted with relief efforts for the earthquake in Pakistan (2005). We weren’t thinking about earthquakes when we were working in China, having focused our efforts on the teaching of science inquiry methods in Sichuan. The May 12th, 2008 Sichuan earthquake hit at 2:28 pm. Its epicenter was a few miles away from Dujiangyan, China. We lost teachers. We lost students. We lost schools. But we didn’t lose hope. Rather, we focused on earthquake science and safety — learning from below the ground and up. We also learned that some buildings sway and others sink, that not all earthquakes act in the same way, and that prevention and planning can save lives. ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 24 Today our Earthquake Science and Safety program teaches students and teachers about the science of earthquakes. Solmaz Mohadjer, a Teachers Without Borders member and geologist from Iran, saw from her work in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan that there is little the way of accurate science and safety content for teachers. Emergencies happen, but they don’t have to be disasters. We launched our program in China immediately following the Sichuan earthquake, with an eye toward scientific validity for adaptation to particular regions, and cultural portability. Form there, it has been implemented in China, Haiti, Mexico, and back to Central Asia. It has also been translated into 6 languages. Short Videos TWB’s Solmaz Mohadjer, Director of Teachers Without Borders’ Emergency Education program on the power of earthquake science education to save lives “Defeating Earthquakes.” Ross Stein, PhD – geologist with the United States Geological Survey (and TWB partner): TEDx talk about earthquake science and safety To Read More about the Girls Quake Science and Safety Initiative Girls Quake Science and Safety Initiative: Teachers Without Borders and USGS Proposal to reach 100,000 girls A Framework for Evaluating the Effect of Earthquake Science Education: Graduatestudent project at George Washington University based upon the TWB Proposal Brochure about Girls Quake Science and Safety Initiative: TWB and USGS effort to attract attention, awareness, and funding for the project ASAP: Education in Emergencies | Johns Hopkins University School of Education & Teachers Without Borders 25

![View DRR Presentation Day 2 [PPT 774.00 KB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005450963_1-d9a539224e4e88c2b7c6d22d8b201673-300x300.png)