USS Olympia

advertisement

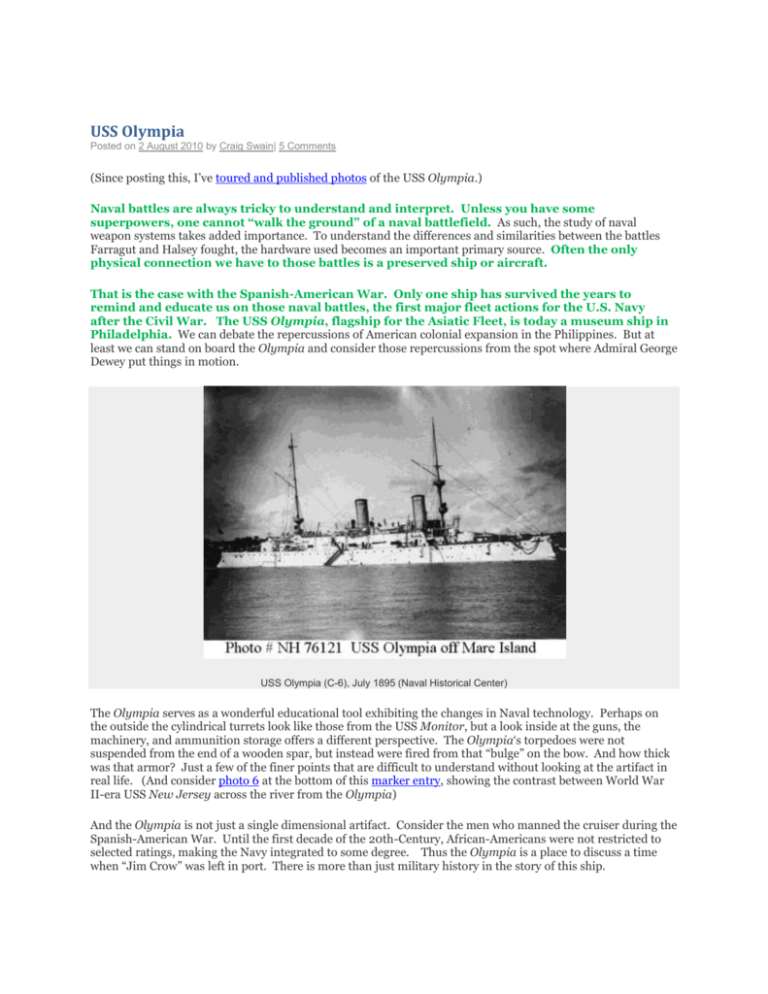

USS Olympia Posted on 2 August 2010 by Craig Swain| 5 Comments (Since posting this, I’ve toured and published photos of the USS Olympia.) Naval battles are always tricky to understand and interpret. Unless you have some superpowers, one cannot “walk the ground” of a naval battlefield. As such, the study of naval weapon systems takes added importance. To understand the differences and similarities between the battles Farragut and Halsey fought, the hardware used becomes an important primary source. Often the only physical connection we have to those battles is a preserved ship or aircraft. That is the case with the Spanish-American War. Only one ship has survived the years to remind and educate us on those naval battles, the first major fleet actions for the U.S. Navy after the Civil War. The USS Olympia, flagship for the Asiatic Fleet, is today a museum ship in Philadelphia. We can debate the repercussions of American colonial expansion in the Philippines. But at least we can stand on board the Olympia and consider those repercussions from the spot where Admiral George Dewey put things in motion. USS Olympia (C-6), July 1895 (Naval Historical Center) The Olympia serves as a wonderful educational tool exhibiting the changes in Naval technology. Perhaps on the outside the cylindrical turrets look like those from the USS Monitor, but a look inside at the guns, the machinery, and ammunition storage offers a different perspective. The Olympia‘s torpedoes were not suspended from the end of a wooden spar, but instead were fired from that “bulge” on the bow. And how thick was that armor? Just a few of the finer points that are difficult to understand without looking at the artifact in real life. (And consider photo 6 at the bottom of this marker entry, showing the contrast between World War II-era USS New Jersey across the river from the Olympia) And the Olympia is not just a single dimensional artifact. Consider the men who manned the cruiser during the Spanish-American War. Until the first decade of the 20th-Century, African-Americans were not restricted to selected ratings, making the Navy integrated to some degree. Thus the Olympia is a place to discuss a time when “Jim Crow” was left in port. There is more than just military history in the story of this ship. USS Olympia (Wikipedia Commons) Earlier this year when I heard the USS Olympia was in dire need of preservation, I was concerned, but figured someone would step forward to save the ship. Press releases indicated the ship required somewhere between $25 and $30 million in order to complete needed repairs, fix berthing arrangements, and stabilize the ship. More money than the Independence Seaport Museum, which currently maintains the ship, can afford. Problem is the Museum has seen a loss of revenue, and perhaps a bit of mismanagement, over the last decade. (Actually, mismanagement is probably going easy – the former museum director was sentenced to fifteen years in prison for getting what he called “my fair share.”) Thus far, private efforts, particularly the Friends of the Cruiser Olympia, have stepped forward, but no financial solutions are set. As things stand today, the Olympia will close for good in November this year. Options to either scrap the ship or sink her as an artificial reef have been discussed. Either option would be a tragic loss of a historical artifact. A loss we could prevent. While I shall hope for the best, I’m going to plan a trip to see the ship before she closes for the season this fall. Hopefully in years to come, my son won’t have to put on a scuba tank to make a second visit. Olympia Remains Afloat, but Repairs are Needed By National Trust for Historic Preservation on July 18th, 2011 Water draining out of the ship’s steel hull at low tide on the Delaware River. (Photo: Independence Seaport Museum) Written by Walter W. Gallas In her nearly 120 years of existence, USS Olympia has shown herself to be a resilient survivor. Today, the world’s oldest steel-hulled warship afloat remains afloat. She rises and falls with the tides of the Delaware River, along whose shores she is moored in Philadelphia, resting at low tide on the riverbed. It is at these times that the damage below her waterline is exposed. USS Olympia on the Delaware River in Philadelphia. (Photo: Preservation Pennsylvania) Recently Jesse Lebovics, the ship’s manager, shared a photograph (above) showing a remarkable sight – water draining out of the ship through a series of holes eaten through the steel hull. According to Jesse, repairs will be made to this area using a “soft patch,” that is, rubber with a backing plate. These repairs can only be done when the area is exposed at low tide, a window of about three hours a day. “I’ve never seen a floating vessel that looked this rough,” Jesse said about the condition of the hull, “It should not look like a pock-marked multicolor meteorite and it certainly shouldn’t have holes.” Nevertheless, Olympia bravely endures. The application and vetting process to determine the ship’s next steward continues, with the goal of identifying a new caretaker and possibly new home toward the end of 2012. The Independence Seaport Museum has committed to continuing to do interim repairs as the application process plays out. The National Trust continues to serve as the home of the USS National Olympia Fund for donations that will either go to the next steward, or – if Olympia reaches emergency status and sufficient funds are available – for repairs to prevent the total loss of the ship. The Olympia will remain open to visitors during this time. Walter W. Gallas is the Director of the Northeast Field Office for the National Trust for Historic Preservation. UPDATE: August 4, 2011 Last week, the hull of the USS Olympia received a 16-foot metal patch (see photo below), timed to correspond to low tide on the Delaware River along the Philadelphia waterfront. Work was completed from floats on the water by the historic ship staff of the Independence Seaport Museum. Damage to the hull is significant, but the patch job at least buys more time until the ship can be taken to dry dock.