Lardy ANWR drilling paper

advertisement

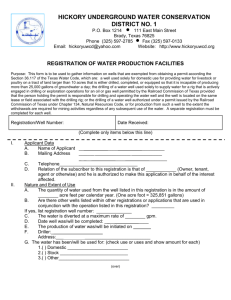

RUNNING HEAD: DRILLING IN THE ANWR 1 Drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) Zachary Lardy University of New Mexico DRILLING IN THE ANWR 2 Introduction: The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) is an oasis in the arctic plains of Northern Alaska, which is in constant danger of destruction by the threat of drilling for oil. This threat has been repeating itself time and time again since the land was discovered to contain billions of barrels of oil. The ANWR is home to the Gwich’in Athabascan tribe of native Alaskans. This essay will explore the arguments for and against drilling and development in the ANWR as well as the legislation that has an impact on this worthy cause. This essay will also summarize and analyze the case “Preventing Drilling in the Arctic Wildlife Refuge: The Gwich’in Tribes and their Role in the National Policy Debate”. In order to fully understand the arguments for and against drilling in the ANWR, we must first explore the impetus for such a move. The United States has become increasingly dependent on foreign oil over the last one hundred years, and this dependency has led to questions about the security of the country as well as our long-term sustainability. Without foreign oil we would be in trouble in just a few short days. This has led policymakers to reach for any and all sources of domestic natural resources to bail the United States out of the current predicament. The problem that exists, however is that those resources aren’t simple to harness and some of them are located in very remote locations. Also, some of those resources are located in pristine unadulterated areas of national treasure. These areas could be devastated by the practice of drilling and extracting those resources. The ANWR happens to be one of the few pristine natural examples of wilderness that should be kept as intact as possible for future generations to enjoy. Also, indigenous people use the ANWR as a subsistence hunting ground and it is home to the Porcupine Caribou Herd. This herd uses the ANWR as its calving grounds and without this pristine environment, there are DRILLING IN THE ANWR 3 worries that the caribou may relocate or fail to thrive. The porcupine caribou are very sensitive to changes in their environment and could be easily displaced by drilling machinery. In 1980, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) was signed by congress with the provision in section 1002 that the land along the costal plain be set aside for future assessment for drilling and development. This happened in an effort to ensure that the area most likely to have a significant oil return was left open for the possibility of drilling in the future should the need arise. The question that almost immediately had to be asked was, “How do we know if the need is there?” The answer to that question contains a litany of responses that all relate to foreign oil dependence and national security as well as the preservation of a national treasure in the ANWR. Arguments exist on both sides of the aisle with regards to exploration in the 1002 area and in the rest of the ANWR. In the following sections we will detail the arguments and analyze their credibility and feasibility. Drilling in the ANWR could have profound consequences nationwide as it may set precedence for other areas to be developed on pristine land. This illustrates the importance that we give attention to the argument of drilling in the ANWR. It is also worth noting that the Gwich’in Tribe is actively lobbying for the protection of this land and they have used unorthodox measures to ensure the sustainability of their way of life in and around the ANWR. We will explore some of these measures and see how they can be applied to other situations like the one in the ANWR where a people’s way of life is threatened. We will explore this after we detail the views of the proponents and then those of the opposition. Proponents Argument: Proponents of drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge view such development as both a stabilizing proposition for the local economy as well as a domestic necessity for both DRILLING IN THE ANWR 4 national security and long-term sustainability. Estimates as of 2001 say as much as 16 billion barrels of oil could be housed under the ANWR. A volume of as much as 1.6 million barrels per day could be harvested (Energy Information Administration 2004, March). This is viewed as a national security initiative because we have become increasing dependent on foreign oil placing us in a compromised situation if those that supply that oil threaten us. Despite the drive to cleaner energy sources, America remains highly dependent on a daily supply of crude oil to keep the economy and the country as a whole running. To illustrate our dependence on foreign oil, it is important to take a look at where the daily supply comes from and the percentages that are utilized from outside the United States. In 2011 the United States imported a net 45% of the crude oil used on a daily basis (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2012). This could very easily lead to a compromising situation in which the United States is unable to sustain its daily use of crude oil and hold the country hostage to other nations that would use crude oil exports as a bargaining chip. It is interesting to note that much of the crude oil that is imported is imported from within the western hemisphere, although some does come from the middle east. “About 22% of our imports of crude oil and petroleum products came from the Persian Gulf countries of Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates. Our largest sources of net crude oil and petroleum product imports were Canada and Saudi Arabia” (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2012). The development of the ANWR would obviously decrease, to some extent, the United States’ dependence on oil out of the Middle East if the need was to arise. There was nearly a consensus agreement in congress in 1989 just before the Exxon Valdez oil spill that the arctic should be opened for exploration. The spill derailed that process. DRILLING IN THE ANWR 5 Another component of the argument for drilling in the arctic is the development of the local economy and the jobs that would be created. American Labor unions anticipate the creation of up to 735,000 jobs around the country (Hinchman, 2001, p. 77). This would boost the local economy as well as account for a reduction in the nationwide jobless numbers. There would also be a decreased dependency on entitlement programs. As the United States emerges from this “Great Recession” jobs will only become a more valid argument for drilling in the ANWR. The job creation capacity of legislation that would open the ANWR to exploration alone could have a profound impact on the recovery of the economy in the United States. Proponents argue, there is untapped potential for job growth in the ANWR and congress is holding up that progress under the pretenses that significant environmental damage will occur without sufficient evidence of such. Regarding the destruction of wilderness, new estimates of the amount of damage likely to be done to the landscape are around twenty-five percent what they would have been ten years ago. This is due to new technology that allows for drilling greater distances horizontally underground to access pockets of crude oil, which may not have been accessible without drilling a new well in the past. Another component of the argument against drilling in the ANWR is the destruction of the delicate plant life on the tundra. These are genuine concerns, however technology and the lessons that the oil companies have learned in Prudhoe Bay can be applied here as well. The common practice when drilling on the tundra now is to bring in gravel pads, which protect the plant life. Also, the waste chemicals and water are often pumped back into the well now. Another argument that has been invalidated is that gravel roads for trucks destroy the permafrost and the tundra. To mitigate this problem, technology now exists to pump ocean water onto the tundra causing it to freeze and create an ice-road, which protects the ground beneath. All of these DRILLING IN THE ANWR 6 points refute arguments posed by opponents that will be articulated below in the opposition section of this essay. The final component that must be addressed as a reason to drill in the ANWR is the increase in the tax revenue both to the federal government as well as to the State of Alaska. The importance of continued tax base growth cannot be overstated as we exit the “Great Recession”. More must be done to capture the available tax revenue where it is possible to do so. It is clear that the American public is not well accustomed to allowing for increases in taxes on the citizens, so corporations have had to bear a lot of weight of the tax structure in the past. This trend is likely to continue, and propositions like drilling in the ANWR only reinforce that developed structure. Drilling in the ANWR, or anywhere for that matter is not a panacea for the revenue problems of the United States, but it may have an impact in the long run. The Opposition: There are many facets to the opposition for drilling in the ANWR. Environmentalists worldwide have taken the issue up with a high degree of success at keeping legislation from being passed which would open the ANWR to development. They are aided by the argument that caribou, musk oxen and polar bears call the ANWR home, a home that could be permanently altered by the footprint of oil and gas drilling in the 1002 area and across the ANWR. The most important wildlife impact would come in the form of reduction in numbers of porcupine caribou, which are a vital lifeline for the Gwich’in tribe in the area. Another common argument held by the locals and environmentalists loyal to the cause is that the oil located in ANWR is not located in one large reservoir like it is in Prudhoe Bay, instead it may be scattered throughout the 1002 area in pockets of unknown size. Some of these pockets may, in fact, be very small. The argument entails a claim that the oil actually extracted DRILLING IN THE ANWR 7 from the 1002 area would likely not have a very large impact on fuel prices or supply, as it would be negligible in size when compared to the other sources we currently employ. Since it is unclear exactly how much oil may be available in the 1002 area of the ANWR, environmentalists claim the cost of the destruction of precious “wilderness” far outweighs the potential gain that could be achieved from drilling there. This argument is articulated to include the fact that only a small fraction of the amount of oil, which we currently depend on from foreign sources would be relieved by drilling in the ANWR. This brings to question the risk to the environment as it relates to the benefit that could be attained. It is logical that there is some risk associated with drilling anywhere and particularly in an area like the ANWR where the plant and animal life is believed to be fragile. However, in other areas of Alaska and around the country for that matter, the wildlife seems to assimilate very well with the equipment, which is hauled in when drilling operations commence. Since President Obama took office in 2009 the tempo has changed at the federal level to one of conservancy as opposed to one of exploration and development under his predecessor President George W. Bush. As foreign oil becomes more expensive and scarce, decisions will have to be made at the federal level that account for the value of “wilderness” in this country and the cost versus benefit of drilling in these areas. The situation in the ANWR remains a critical precedence center for national politics and law. The Gwich’in Response: Gwich’in means “Caribou people”, and as the name implies, the tribe is largely dependent on the Porcupine Caribou herd, which resides in and around the ANWR. The concern about development of the ANWR with regards to the caribou herd is the fact that this development could inhibit the herd’s migration to its summer calving grounds, and may DRILLING IN THE ANWR 8 ultimately affect the sustainability of the herd and therefore the Gwich’in tribes. To understand the gravity of the situation in the ANWR with regards to the Gwich’in tribe, it is important that we explore the response of the tribe to the threat of development of the calving ground for the porcupine caribou. In 1988, the Gwich’in tribe felt they were backed into a corner and had no way out, but to fight for their livelihood. This led to the Gwich’in Steering Committee, which has since taken up the cause of protecting the ANWR from development. This has required a complete shift in the attitudes of the tribal members from those of survivors to those of political activists. The education for such an endeavor now starts during childhood for young members of the Gwich’in tribe. This is an effort to continue a culture of distributed leadership among tribal members where each takes ownership for the preservation of their way of life, and everyone has a say in how the fight to protect that way of life takes place. Sarah James, the spokesperson for the Gwich’in Steering Committee, and a tribal member, has taken it upon herself to show the tribe the way out of this threat. Another facet of the argument for development in the ANWR that should be addressed here is that the Gwich’in tribe has come under some scrutiny for some of its practices over the years. They have only recently begun to transform their villages to a more conservative attitude. This includes a greater accountability for their wasteful actions. They are also more mindful of their impact on the land as they believe there is a sacred link between the people and the land. An example of the argument that the Gwich’in people are somewhat hypocritical when they argue against development of the ANWR is the fact that much of the transportation in Arctic Village, one of the largest Gwich’in villages, consists of the use of snowmobiles, which use gasoline that could be produced in greater quantity if development of the ANWR was allowed. Another facet is the profound reliance on generators, which marks a way of life for the Gwich’in tribe so far DRILLING IN THE ANWR 9 north in Alaska where sometimes the sun doesn’t shine for months at a time. To mitigate these complaints, the Gwich’in steering committee has directed tribal members and leaders to encourage the use of more green technology like solar panels. The challenge that the Gwich’in tribe must overcome is the shaping of the problem in the ANWR as one of human rights. This has proven difficult to do, although they are experiencing some success of late. The culture shift has been one of advertisement in a way. The Gwich’in tribe has become adept at selling their cause to those who can make a difference and have had success in doing so. To do this, they’ve had to commit to attending meetings and conferences that they would never have attended without this pressing issue threatening their way of life. This has led to an increased awareness of problems worldwide and improvement in the level of education of the younger generations. Conflict in the Arctic: It is also important to mention the disagreements between the Inupiat Eskimos of the North Slope of Alaska and the Gwich’in tribe who are their neighbors just to the south. The Inupiat of Kaktovik, Alaska have traditionally embraced oil exploration and development on the North Slope of Alaska. They have also embraced a way of life that does not depend nearly as much on subsistence hunting as does the lifestyle of their southern neighbors, the Gwich’in. The irony lies in the double standard they have created. The Inupiat have continuously opposed drilling in the waters around channels that the bowhead wale calls home because the bowhead wale is one of the last links to subsistence hunting they have. The reasons behind this opposition lie in the high likelihood of problems with drilling offshore in an environment, which has hostile weather conditions as well as high-volume oil production capacity. It is ironic that the Inupiat Eskimos of Kaktovik would oppose drilling DRILLING IN THE ANWR 10 offshore to protect their subsistence heritage, while supporting drilling in the arctic that could have the same effect on their neighbors to the south, the Gwich’in people. This is a good reason the Gwich’in people must mobilize their other supporters. Analysis: The Gwich’in tribe has adapted to the political environment they are faced with in order to make a name for themselves on the international stage. This is a critical element to ensuring the cause is heard and acknowledged. In this case, it was crucial that the Gwich’in Steering Committee be developed and takes control of the situation that is threatening the tribe. It was also crucial in the case for the Gwich’in tribe to mobilize their allies. They needed to take what was happening in Alaska and make it similar to situations that could happen anywhere in the country or the world. This brought sympathetic, like-minded groups of people to the fight for the ANWR and was a crucial stepping-stone to the position the tribe is in today. It is clear that our national security is impacted by our dependency on foreign oil. This leads us to the conclusion that the only real fix for the problem is a decreased dependency on fossil fuels and an increase in use of renewable energy sources. The Gwich’in tribe has recognized this on a micro level within their communities, however they have come to this conclusion because of pressure from critics of their position to drilling in the arctic. If drilling is not going to take place in the arctic, it is their responsibility as well as that of the rest of the country to become more energy independent. This independency will only come from a reduction in the use of fossil fuels. Human rights issues are always more heavily debated than those that just involve environmental causes. It may be going too far to say that opening the ANWR to drilling would be an act of genocide on the Gwich’in tribe; however there undoubtedly will be some kind of DRILLING IN THE ANWR 11 impact on their way of life or their ability to continue the heritage they have had for so many years. They have been able to mobilize friends and supporters to their cause, but it is yet to be seen whether that is enough. They may have to step up their efforts from a legislative standpoint and work to place tribal members in legislative positions in both Alaska and the United States. There is a history in Alaska of conflict between indigenous tribes and the government. For example: Project Chariot, in which the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), with the blessing of the State of Alaska, planned to conduct atomic weapons tests under the pretext of blasting out a deep-water harbor near an Inupiat village in the northwestern part of the state. (Chance, 1990) These tests could have been catastrophic to the health of native Alaskans living in the area and were ultimately called off. A situation like this could be developing in ANWR though and it will take diligence on the part of the Gwich’in tribe and their allies to keep it from taking place. DRILLING IN THE ANWR 12 Reference List Chance, N. A. (1990). The Iñupiat and Arctic Alaska : an ethnography of development. Fort Worth: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Hinchman, S. (2001). Endangered Species, Endangered Culture: Native Resistance to Industrializing the Arctic. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Anchorage: USDA Forest Service. U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2012, July 13). Energy In Brief. Retrieved April 4, 2013, from U.S. Energey Information Administration Foreign Oil Dependence: http://www.eia.gov/energy_in_brief/article/foreign_oil_dependence.cfm