Autopoiesis Structural coupling Cognition-Maturana-Comments

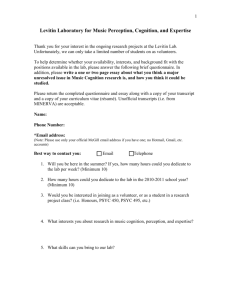

advertisement

Dcg design computation group at MIT http://dcg.mit.edu/2011/09/week-4-autopoesis-structuralcoupling-and-cognition/ Autopoesis, Structural Coupling and Cognition September 26th, 2011 by Daniel Rosenberg By Humberto Maturana Romesin. Cybernetics & Human Knowling, Vol. 9, No 3-4, 2002, pp. 5-34. 1. wortmann says: October 11, 2011 at 9:27 am Of apples and vacuum cleaners – a critical commentary on Maturana’s ‘Autopoiesis, Structural Coupling and Cognition’ Maturana’s philosophy has been labeled as Radical Constructivism, and such has been the object of controversial debates since the 1970ies. His position asserts that all experiences, and therefore all knowledge, are internal to an organism, as apparent in the following statement: ‘As living systems are structure determined systems, all that occurs in them or to them, happens determined in their structure. […] An external agent can only trigger in the living system a structural change determined in it. An external agent, therefore, does not and cannot be claimed to constitute an input for the living system because it “tells” nothing to the living system about itself or about the medium from which it comes. […] It is in this sense that I claim that a living system does not have inputs or outputs, and that its relation with the medium cannot be described in informational terms.’ (p. 24) In short, a living system cannot receive inputs because it is structurally determined, that is all changes to the system are predicated on its internal structure. This assertion is based on Maturana’s definition of all living systems as molecular autopoetic systems: ‘A living system as a molecular system is a structure determined system, and everything that happens in it or to it, happens in each moment determined by its structure at that moment’ (p.12). This is the case for all living systems, since ‘it is only in the molecular domain that systems like living systems can exist because it is only in this domain where autopoiesis can take place’ (p.14). In other words, all living systems are structurally determinate, because all living systems are molecular autopoetic systems. But what constitutes a molecular autopoetic system for Maturana? A molecular autopoetic system is ‘a closed network of molecular productions that recursively produces the same network of molecular productions that produced it and specifies its boundaries, while remaining open to the flow of matter through it [...]’ (p.8). Therefore, all living systems consist of interactions between molecules, and this is why they are structurally determined. I would argue that interactions between molecules can only be understood as determinate in the sense that, under identical conditions and given a set of molecules, the same biochemical reaction will occur. This implicit claim is central to Maturana’s argument, and is extended to cognition, consciousness and language towards the end of his discussion. However, it is problematic to frame cognition and consciousness exclusively in the molecular sphere: The natural sciences can be construed as a hierarchical set of explanatory frameworks, with each set resting on a different set. Organisms can be explained in terms of molecular biology, molecular biology in terms of chemistry, and so on right down to the elementary particles of quantum physics. Crucially, each set carries with it a description of properties that are only valid and specific for each set. For example, a falling apple can be construed according to Newton’s laws or Einstein’s Relativity, but, as of today, not in terms of quantum theory (which would describe the apple as a probabilistic wave form, but fail to account for gravity). In addition, it also does not yield additional explanatory benefits to include relativistic effects when discussing the falling apple. This is the case because relativity is only relevant for phenomena occurring with a speed relatively close to the speed of light. Therefore we can say that a non-relativistic and nonquantum framework such as Newton’s laws is appropriate for and specific to falling apples and other objects with speeds significantly slower than the speed of light. In the same vain, I would argue that human consciousness cannot be satisfactorily framed in terms of molecular interactions. One reason is that contemporary biochemistry fails to explain which properties of molecules lead to the experience of self-awareness, another that molecules are most likely an inappropriate scale when looking at cognition and consciousness (Again, it is unrepresentative to look at an apple in terms of quantum physics, or even chemistry, when we are interested in its properties as a falling object). Because of that, even a complete description of the biochemical state of a human brain with its billions of neurons would fail to explain the actions of a human in a relevant fashion. On a different but related note, another challenge to Maturana’s theory of cognition is presented by robotics and artificial intelligence: Let us consider a simple robot that navigates obstacles employing Rodney Brook’s Subsumption architecture (i.e. the programming of the robot does not include an internal representation of the world). Cameras and sensors detect obstacles based on filtering algorithms, and a deterministic tree-search is employed to calculate the shortest route. In the last ten years, these types of robots have become common to the point that they can be purchased as autonomous vacuum cleaners by ordinary consumers under the brand name ‘Roomba’. According to Maturana, we would have to assign such a ‘Roomba’ cognitive capacities, because ‘knowledge is something that an observer assigns to a human being or to a living system when he or she sees such an organism behaving adequately (in operational coherence) with a changing medium’ (p.27). As ‘it does not matter if the living system observed is an insect or a human being’ (p.26) we surely also have to extend this observation to robots: It is no question that a robot avoiding (moving) obstacles when vacuuming the living room fit’s Maturana’s definition of behaving adequately. In that light, it seem downright absurd to claim that ‘any attempt to explain the adequate behavior of human beings, or any other living system, (which in daily life we call cognition) as if it were the result of some computation made by the nervous system using data or information obtained by sensors about an external objective world, is doomed to fail’ (p.27). After all, the preceding sentence perfectly describes how the ‘Roomba’ was designed and functions. This is not to say that such as robot is intelligent or conscious, or that human cognition works along the same lines a described for the ‘Roomba’, but only to show that Maturana’s framework is insufficient to describe cognition in general. In conclusion, we have to reject Maturana’s structural determinism, or at least the chain of arguments that leads to it, because it rests on the fundamentally flawed premise that all living systems are molecular systems exclusively, and can be explained as such. Maturana’s framework of cognition also contradicts basic insights from artificial intelligence. It is conceivable that advances in neuroscience might be able to reconcile psychology, artificial intelligence and molecular biology at some future point in time. However, such a hypothetical unified theory of cognition would most likely required a more refined frame work than Maturana’s structural determinism, analogous to the fundamental uncertainty that quantum theory has introduced into formerly determinate physics. Log in to Reply 2. Theodora Vardouli says: October 17, 2011 at 7:52 am I was very intrigued by Thomas’ response, epitomized in his conclusion: “We have to reject Maturana’s structural determinism, or at least the chain of arguments that leads to it, because it rests on the fundamentally flawed premise that all living systems are molecular systems exclusively, and can be explained as such”. Although I do not intend to take the position of a Maturana apologetic, I found that although Thomas’ arguments might be rhetorically sound, they are based on an interpretative scheme of “Autopoiesis, Structural Coupling and Cognition”, which can be contradicted by Maturana’s own arguments. The purpose of my comment is to locate some of these points of tension and open them to discussion. Thomas observes an implicit determinism, in the Newtonian sense, in Maturana’s discourse. He writes: “I would argue that interactions between molecules can only be understood as determinate in the sense that, under identical conditions and given a set of molecules, the same biochemical reaction will occur. This implicit claim is central to Maturana’s argument, and is extended to cognition, consciousness and language towards the end of his discussion.” However, it is my impression that this understanding is somewhat misaligned with Maturana’s definition of structural determinism: “A structure determined system is a system such that all that takes place in it, or happens to it at any instant, is determined by its structure at that instant” In this argument, structure is not seen as a stable, undisturbed entity but as immanently changing within a set of organizational constraints. As Maturana denotes, “The structure of a system is open to change [...] a system conserves its class identity, and stays the same while its structure changes, only as long as its organization is conserved through those structural changes” Also, in my reading, the rejection of the notions of input and output does not reinforce an ontological discussion (stable entities, objects abiding to their own transcendental rules) but does precisely the opposite: defines entity and identity as the result of the constant interplay of systems, where it is impossible to define clear cut “IN”s and “OUT”s. Thomas also accuses Maturana of reductionism, claiming that he subjects all of nature and human cognition in one interpretative scheme. He says: “It is problematic to frame cognition and consciousness exclusively in the molecular sphere; The natural sciences can be construed as a hierarchical set of explanatory frameworks [...] Maturana’s framework is insufficient to describe cognition in general”. However, Maturana explicitly states that he does not intend to produce an explanatory or ontological framework: “I think that what is commonly presented as an epistemological difficulty is the frequent mistake of using autopoiesis as an explanatory principle” and identifies his epistemological shift as “abandoning the question of reality for the question of cognition while turning to explain the experience of the observer with the experience of the observer” In short, I feel that Thomas’ argumentation does not escape “our cultural refusal to accept that things, systems, relations, and entities in general, arise into existence in the instant in which the conditions of their constitution take place.” and in that sense, although logically sound, can be seen as asymptotical with the main premises of Maturana’s discourse being therefore unable to either validate or falsify it, as they participate in different discussions. Log in to Reply