Introduction to advanced topics in field epidemiology

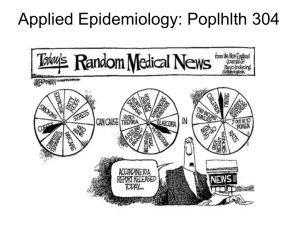

advertisement