Accessible Word Doc - Equip for Equality

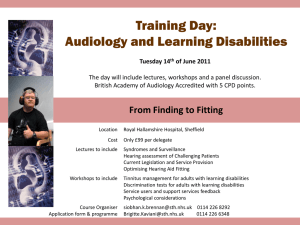

advertisement