Professor Matthew Krystal SOA 363 – Mexico and its Neighbors 06

advertisement

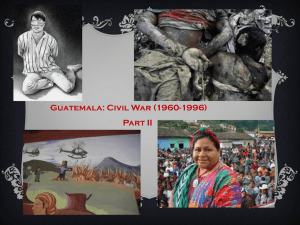

1 Professor Matthew Krystal SOA 363 – Mexico and its Neighbors 06 June 2014 The Maya Welfare: An Examination of the Guatemalan Economic Policy, Maya Cultural Identity Revitalization, and Issues of Food Insecurity and Poverty Introduction The globalizing world of the twenty-first century allows many developing nations to compete in the global economy. For the Maya people in Mesoamerica, it alters their lifestyle in light of the government, their cultural identity, and issues of poverty. This paper will begin by examining the past and present government economic policy of Guatemala and its impact on the Maya people. It will then lead into the discussion of the Maya identity impacts on the local and global scale in relation to its economy. Finally, it examines the ongoing rural poverty in Guatemala given the large agricultural export growth, leaving the poor with increased food insecurity. All three subtopics provide anthropological research that reflects the concern that the Maya people have with their welfare. This paper will provide the pertinent background information needed for a greater understanding of the socioeconomic conditions of the Kaqchikel Maya family from Chimaltenango, Guatemala, featured in the ethnographic film What We Learned from Our Grandparents. Part I: Past and Present Guatemalan Economic Policy Twentieth-century Guatemalan Economic Policy The push for economic modernization in Guatemala began in 1950 with the arrival of the World Bank. The commission was led by G.E. Britnell, professor in the Department of Economics and Political Science at the University of Saskatchewan. The report entitled “The 2 Economic Development of Guatemala” was published in 1951 in the Canadian Journal of Economic and Political Science. The commission described the disadvantages of the indigenous populations’ geographic isolation from urban settings. Concentrated in poor mountain lands, Guatemalan indigenous populations suffer from erosion and deforestation of the hills, among other major environmental causes that are unsuitable for agricultural work. Britnell and his team reported that the minimal industrial development is attributed to the emphasis on poor agricultural farming in these mountain lands. In order to resolve these economic issues, the commission provided solutions that would greatly impact the indigenous populations of Guatemala (Goldin 2009:11). The push for a single economy would, in theory, “improve education, health, and nutrition, and lead to the development of new occupations for the indigenous populations of the highlands. They also recommended the resettlement of portions of the population into regions that are” suited to advanced agriculture (2009:11). The commission deemed that the labor production should focus on cattle, milk products, and horticulture, as well as native crafts that could be great profit generating exports to developed nations such as the United States. They deemed the production of corn was an unsuitable crop for economic gains and competition in the world economy. Another major modernization suggestion made by the commission was the emphasis on “establishing small manufacturing plants” to address the issues of unemployment, offering indigenous peoples exposure and work to modern labor tasks. They also recommend the resettlement of the indigenous populations into structured villages “that would facilitate sanitary control and social and cultural stability” (2009:12). Britnell revisited this report in a presidential address delivered at the Joint Meeting of the Canadian Historical Association and the Canadian Political Science Association at Ottawa, June 3 14, 1957. Six years after he directed the commission, Britnell still held firm beliefs to the success of these economic policy implementations in Guatemala. He boasts that “‘The present rate of progress, are clearly in a position increased by a better utilization of both human and natural resources. Guatemala is […] typical of many under-developed countries throughout the world. Among its most striking features are: a low level of per capita production, particularly of the under-employed agricultural population; a relatively high rate of population growth; relatively low levels of public and private investment; periodic flights of capital; a shortage of skilled labour; inadequate transportation and power generation; a high rate of illiteracy; low standards of education, health, and sanitation; indifferent standards of public morality; and finally, acute internal political instability. It may, perhaps, be noted that as a slight offset to this gloomy array of debt items a recent survey cited certain advantages which Guatemala enjoys over some underdeveloped countries, especially ‘a growing urban middle class and a considerable number of successful entrepreneurs in agriculture and industry who have managerial experience and technical knowledge, and an even larger number of would-be entrepreneurs who lack capital.’”1 (Britnell 1957:455) Britnell was convinced that the economic policy implementations made by the World Bank commission in 1950 gave rise to an urban middle class. This, in turn, gave prospective entrepreneurs increased opportunities to pursue technical work beyond agriculture. Despite the long list of under-developed attributes prevalent in Guatemala, Britnell proposed they are striving towards a more productive economy for the welfare of the indigenous populations. Despite the good intentions of these economic policy implementations, they brought forth a whole new array of issues which include “new migration patterns, voluntary resettlement because of the establishment of maquiladora industries, growth of petty capitalist workshops and small local factories, reallocation of land in the more fertile areas for purposes of exporting vegetables, and the planned and forced resettlements of the ‘development poles’ instituted by military governments in the early 1980s” (2009:12). The neoliberal policies of the 1970s and the military dictatorship in the 1980s heavily influenced the current state of Guatemala’s economy in conjunction with the push for modernization by the World Bank commission. 1 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The Current Economic Position and Prospects of Guatemala (mimeo., Washington, 1955), 2. 4 Twenty-first Century Guatemalan Economic Policy Globalization has dramatically changed Guatemala’s economy as it seeks to “capitalize on each country’s comparative advantage,” which is cheap manufacturing labor in factories and sufficient agricultural export revenue for Guatemala (2009:12). As a result, the country’s economy is commanded by the private sector which generates about 85% of gross domestic product (The PRS Group 2013:21). With the private sector push, problems delaying economic growth include illiteracy and low levels of education; inadequate and under-developed capital markets; and lack of infrastructure, particularly in the transportation, communications and electricity sectors. The distributions of wealth remain unequal as “the wealthiest of 10% of the population receives almost one half of all income; the top 20% receives two-thirds of all income” (The PRS Group 2013:22). All of these distributions discount the indigenous populations as they remain largely outside the political, economic, social, and cultural mainstream. The Guatemalan government does not consult them before making decisions that could affect their interests. The two major labor processes—field and factory—provide many perspectives about the economic welfare for the Maya peoples. One such perspective is the measure of self-worth through labor wages. In 2007, a Maya individual made “about US$6 per day” (Goldin 2009:148). While many Mayas are enticed by the increased wages earned in factories, in reality wages earned “in the two contexts (field and factory) were about the same. In the factory, personal behavior is perceived by workers to be a factor in the determination of wages: submissiveness, obedience, and ‘doing what you are expected to do’ can allow you to ‘improve yourself,’ ‘to progress’” (2009:148). The constant push for a globalized economy has made many Mayas compromise their traditions and values for a more competitive, wage-based factory labor mentality, steering away from their agricultural roots. 5 Part II: Maya Cultural Identity Cultural Identity Formation Background The evolving labor preferences among younger Maya generations toward factory work have brought forth different challenges to the preservation of the Maya cultural identity. There is a lot of political debate in the identity formation of the Mayas. In order to create a unified cultural identity, the group must “share a sense of solidarity, are organized to accomplish specific objectives, and express membership through display of symbols unique to their association” (Schortman et al. 2001:312). The cultural group must strive for some sort of political autonomy and preservation of their social norms, values, and traditions. The hierarchy of social order further creates “an existing framework of affiliations. Other identities, such as those based on gender, age, kinship, and earlier political formations, are unlikely to disappear as long as they are used to organize activities and guide interpersonal interactions” (2001:325). This is the case for the Mayas as many Maya communities attempt to operate independently from the state through their strong sense of solidarity. Maya Citizenship in Guatemala The Maya authorities constantly negotiate citizenship within the context of indigenous claim in Latin America. These local authorities give meaning to their political practices and indigenous identity upon negotiating legal frameworks with the Guatemalan federal government. Citizenship in Guatemala is a contentious issue among the Mayas as they view their homeland is taken away from them since the time of colonization on the land. Yet, not all Mayas feel threatened by identifying as a Guatemalan citizen. In this new emerging Maya identity category of urban Mayas, local authorities “negotiate forms of citizenship are mediated by religion and rural-urban divisions. Increasingly, ‘modern’ forms of knowledge are required in order to be 6 included in the political system” (Rasch 2011:68). By acquiring these modern forms of knowledge, everything from the Guatemalan federal government agenda with the indigenous communities to the daily interactions with Guatemalan common folk outside of the indigenous populations, some indigenous authorities find their Guatemalan citizenship status useful for seeking political office. These emerging urban Maya members seek to connect the traditional, rural Maya traditions with the modern, urban hybrid Maya-Guatemalan identity. Maya Cultural Identity Revitalization Movements Despite the urban Mayas’ effort to connect with the non-indigenous citizens, they still seek to preserve their culture and heritage through cultural revitalization movements. These movements include preserving the native Maya language, theater, dress, education, and religious practice. Ethnographic work done by anthropologists since the 1980s has revealed the importance of these cultural revitalization movements to the Mayas. The military dictatorship in the 1980s threatened and scarred all Guatemalan citizens and indigenous members. The native Mayas were more concerned with the preservation of their culture than the threat from the guerrilla revolutionary organizations such as the URNG (Guatemalan National Revolutionary) (Loewe 2009:257). There is a complex relationship between urban and rural Mayas as a result of this cultural revitalization movement. Urban Mayas seek to build repertoire about their status to work in this globalized economy. Rural Mayas seek to preserve their cultural identity. Through the “complex nexus of relationships which exist among scientists, entrepreneurs, politicians, tourists, and local Maya residents, and give young ethnographers new things to think about,” the challenges of Maya cultural identity revitalization reflect their economic struggles for selfautonomy and welfare benefits. These socioeconomic challenges lead into complicated issues of poverty and food insecurity. 7 Part III: Poverty and Food Insecurity for the Guatemalan Mayas Food Insecurity in Guatemala Following the conquest and colonization by European powers more than 500 years ago, the Maya suffered under-nutrition, with short stature, thinness, and high infant mortality. Today, the Maya face a new mixture of nutritional threats from diets that are supplied by multinational corporations. Income and food prices greatly influence the intake of micronutrients by individuals in Guatemala. Before the food price crisis in 2006, “the probability of inadequate intakes was high for vitamins A and B-12, folate, and zinc in the poorest households of the country” (Iannotti et al. 2012:1572).These micronutrient intakes provide many benefits for individuals. There is vitamin A in carrots and spinach and any greens. Vitamin B-12 is in a lot of seafood, meat, and dairy. Folate is in beans and broccoli. Zinc is in seeds and beef and lamb (2012). Since the 2006 food price crisis, these micronutrients yielded the largest income disparities. When reductions in household income occurred alongside this economic downside, “the probability of inadequacy increased in greater proportions for zinc, […] across all quintiles, and vitamin A and folate in the poorest quintile” (2012:1572-1573). Economics strongly influence the nutritional intake in three important ways. First, the micronutrient intake substantially contributes to the global burden of disease. There is a significant drop “in underweight prevalence in many parts of the world, but stunting and other manifestations of micronutrient deficiencies remain” (2012:1573). Second, economic policies highly affect household income for food purchases. The third important influence is that in order to “better understand economic drivers across the entire distribution of intakes. […] (The findings argue) for region- and population-specific analyses of different economic determinants. 8 Price and income varied from initial economic conditions, local consumption patterns and culture, market conditions, climate, and food availability (2012:1573). The nutrition epidemiology is an important factor as “the demand for food is not driven by its micronutrient composition but rather by prices, income, taste, culture, and potentially by knowledge about nutritional value as a whole” (2012:1573). Vitamin B-12 intake in a typical Guatemalan diet is concentrated in the meat, poultry, and fish and milk, eggs, and dairy groups. This results to high price-nutrient associated with these food groups and this nutrient (2012:1573-1574). The problem is associated with poor-quality diets in Guatemala linked to poorer households. Maya mothers and children are most affected by the poor-quality diets in these low socioeconomic status groups (Bogin et al. 2014:24). Evidence of stunting and thinness are most common in traditional rural villages of the middle twentieth century. Local foods such as tortillas are part of the Maya diet, and yet, they are “increasingly globalized. Factory manufactured tortillas, for example, may be made from non-local ingredients, even nontraditional ingredients and may displace local production and sales networks” (2014:29). These ingredients greatly affect the nutritional intake of indigenous communities as they lack the healthy benefits of natural ingredients in typical Maya diets. With rising food prices and income disparity in Guatemala, these two factors greatly influence the lack of micronutrient intakes by the indigenous Maya communities. Public Policy Programming to Alleviate Food Insecurity in Guatemala Government policy programming should incorporate the economic factors of income and food prices with other interventions. Policy programming for nutrient intake should start at the early childhood stage. By improving nutrition in early childhood stages, it can “protect against micronutrient deficiencies during acute crises or even sustainably address under nutrition over 9 the longer term, the household wealth and intake relationship” (2012:1574). Some practical solutions are “asset building, microcenterprise development, or cash transfer programs. Food supplements or vouchers may also be required during periods of high food prices” (2012:1574). By improving micronutrient nutrition in Guatemala, it “may ultimately require household economic interventions targeting the poor” (2012:1575). Poverty in Guatemala The human development report from 2008 indicates that 73% of Guatemalan citizens are poor and 26% are extremely poor. This is opposite of the indigenous population in Guatemala as they are 35% poor and 8% extremely poor. Indigenous peoples’ life expectancy is shorter by 13 years, and only 5% of university students are indigenous. Despite the apparent economic disparity for the indigenous population, they account for 61.7% economic outputs for the nation. A majority of the economic growth for the Guatemalan Maya communities comes from agricultural export growth. The increased export of nontraditional export products (NTE) include “seafood, manufactured goods, apparel, textiles, wood products, fruits, vegetables, spices, plants, flowers, and handicrafts” generated “41 percent of the total revenues obtained from exports” (Goldin 2009:18). These products are directed at developed nations such as the United States and Canada. However, there are varying limitations to the pro-poor agricultural trade in Guatemala. A closer examination of the sugar and snow pea sectors prove the limitations of agricultural trade in Guatemala and the increased issues of poverty affect the welfare of the Maya communities. The sugar sector comprises of “wealthy families from the economic elite” as the main beneficiaries. Sugar allows mass production of dietary foods for mass consumption on a global scale. Despite the wealth poured into the wealthy families, the laborers “earn below-subsistence wages” (Krznaric 2006:130). The snow pea sector comprises of “small-scale farmers” who have 10 received “insufficient government support to allow them to compete with larger producers” (2006:130). These two sectors demonstrate the lack of economic benefits of agricultural trade growth for the Maya indigenous populations. Ultimately, agricultural trade growth “has not fundamentally altered the breadth and depth of rural poverty in Guatemala, nor has it had a substantial impact on land and income inequality” (2006:130). Public Policy Programming to Alleviate Poverty in Guatemala There is a great need for public policy programming for the Maya economic welfare. To begin, Guatemala needs “basic human capital and supply side reforms such as improved health care, education and rural infrastructure” (2006:131). The government should ultimately focus on providing aid and support to the small-scale farmers to alleviate rural poverty, which affects a majority of the indigenous Maya populations. They need to implement nontraditional agricultural export (NTAE) production among the small-scale farmers. There is also a strong necessity of equal access to credit and insurance and marketing support. Women need to be ensured benefits as they are oftentimes “disproportionately burdened by shifts towards NTAE production, for instance by losing economic leverage within the household” (2006:131).There needs to be a strong focus on empowering women in the traditional Maya households to encourage their economic productivity for their family, community, and state. Another major economic policy implementation is the full enforcement of the labor code. The government needs to own up to its legal obligations “by enforcing its own labour code” so the rural poor would gain greater benefits from agricultural trade growth (2006:131). The labor code specifically states the provision of the minimum wage for rural workers and “other nonwage benefits such as the 13-month salary bonus. This should also have an effect on reducing wage disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous people, and between women and men. 11 The benefits of minimum wage could help raise subsistence levels, and non-wage benefits in the labor code could be extended to cover temporary and seasonal workers” (2006:131). Another policy implementation the government needs to focus on is the land-titling programs and land reform. This is especially urgent as “extreme poverty and malnutrition are increasing. It would permit the poorest rural inhabitants to meet their subsistence needs, present opportunities for growing cash crops and provide collateral for obtaining loans to pursue educational and other goals” (2006:132). The government could contribute to the pro-poor growth by leading a project to provide “market-based solutions” and giving “poor farmers legal title to land that they have often farmed for decades” (2006:132). With financial support, the Guatemalan government should pour resources to make peace accords of land inequality disputes by “ceasing use of force, and respecting human rights and legal procedures, when dealing with land occupations” (2006:132). The hardest component to tackle the issue of poverty in Guatemala is changing the elite attitudes about the poor. The economic elite have “substantial influence” over private sectors of “sugar, bananas, coffee, forestry, food and beverage, cement and chicken,” just to name a few (2006:132). There needs to be an implementation of “long-term strategies of change” by showing the economic elite the social issues that are facing the poor. The government could provide “cultural programs” that allow the economic elite to “experience the lives of poor” (2006:132). There could also be “one-to-one dialogues” between the economic elite and the indigenous farmers (2006:132). By encouraging empathy and understanding through these programs, reforming the economic elite’s perception of the indigenous poor could help combat the issues of poverty in Guatemala. 12 Conclusion This paper has highlighted three pertinent background topics about the indigenous Maya concern with their welfare as a result of their government economic policy, their cultural identity revitalization movements, and their issues facing food insecurity and poverty. Through colonization and globalization, the Guatemalan indigenous Maya communities have faced dramatic changes in their livelihoods. The 1950 World Bank commission has pushed forward the notion of modernization for the Maya populations. They gathered the entire community into one single economy at an attempt to improve education, health, and nutrition. By providing new occupations through the push of nontraditional agricultural export products (NTAEs) and nontraditional export products (NTEs), the World Bank commission sought to bring economic growth to the rural Maya communities of the time period. The lasting impacts of this modernization efforts resulted in neoliberal practices later in the 1970s and 1980s by military dictatorships, which resulted in new migration patterns, voluntary resettlement, and reallocation of land for farming purposes. Despite all the efforts of this modernization process, the Maya communities seek to preserve their cultural identity and heritage in light of all the external influences on their population and location. While there is a stark discrepancy between rural and urban Mayas— rural prefers the traditional lifestyle, while the urban Mayas prefer greater interaction and connections with non-native Mayas—both groups seek to improve the reputation of Mayas to non-indigenous peoples. Even during the 1980s revolutionary regimes, the Mayas were more concerned at preserving their native language, dress, religious practice, and theater than to fight against these military groups. 13 The Maya has a strong desire to overcome all social issues, in particular their increased food insecurity and poverty. There is a link between the low micronutrient intakes that affect the growing situation of poverty among indigenous Maya communities. Some practical solutions to combat food insecurity issues include food supplements or vouchers during times of high priced food items. Poverty that is affecting the Mayas is a result of economic inequality controlled by the wealthy elite families. They take control of most of the agricultural sectors such as bananas, sugar, snow peas, and coffee. The government needs to implement multiple reform policies including cultural programs to educate the wealthy elite of poverty issues facing the indigenous populations, providing land entitlements to small-scale farmers, and offering opportunities for education attainment and personal growth in light of the demands of the global economy. 14 Bibliography Britnell, G.E. 1957 Under-Developed Countries in the World Economy. The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 23(4):453-466. Bogin, Barry, with Hugo Azcorra, Hannah J Wilson, Adriana Vazques-Vazquez, Maria Luisa Avila-Escalante, Maria Teresa Castillo-Burguete, Ines Varela-Silva, and Federico Dickinson 2014 Globalization and children’s diets: The case of Maya of Mexico and Central America. Anthropological Review 77(1):11-32. Goldin, Liliana R. 2009 Global Maya: Work and Ideology in Rural Guatemala. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press. Iannotti, Lora L., with Miguel Robles, Helena Pachon, and Cristina Chiarella. 2012 Food Prices and Poverty Negatively Affect Micronutrient Intakes in Guatemala. American Society for Nutrition 142(8):1568-1576. Krznaric, Roman. 2006 The Limits on Pro-poor Agricultural Trade in Guatemala: Land, Labour and Political Power. Journal of Human Development 7(1):2006. Loewe, Ron 2009 Maya Reborn. Reviews in Anthropology 38:237-262. Mcllwaine, Cathy and Caroline Moser. 2003 Poverty, violence and livelihood security in urban Colombia and Guatemala. Progress in Development 3(2):113-130. The PRS Group, Inc. 2014 Political Risk Yearbook: Guatemala Country Report. Political Risk Services 1-50. Rasch, Elisabet Dueholm 2011 Representing Mayas: Indigenous Authorities and Citizenship Demands in Guatemala. Social Analysis 55(3):54-73. Schortman, Edward, M. with Patricia A. Urban and Marne Auesec 2008 Politics with Style: Identity Formation in Preshispanic Southeastern Mesoamerica. American Anthropologist 103(2):312-330. 15 Appendix A: Annotated Suggested Reading List B: Pre-viewing Questions C: Post-viewing Questions 16 A: Annotated Suggested Reading List Krznaric, Roman. 2006 The Limits on Pro-poor Agricultural Trade in Guatemala: Land, Labour and Political Power. Journal of Human Development 7(1):2006. Krznaric’s examination of poverty and agriculture in Guatemala provides great information for my discussion of poverty and food insecurity in Guatemala. The article explores the ongoing rural poverty in Guatemala since the early 1990s and correlates it with the agricultural export growth. He takes a closer look at two agro-export sectors—sugar and snow peas—and their impacts to alleviate poverty by the country’s economic elite. Overall, the country’s economic elite limits on pro-poor growth and he provides several policy recommendations to promote propoor growth: full implementation of the labor code, a national land-titling program, and cultural programs to change elite attitudes towards poverty and development. This is a critical article being from Journal of Human Development, as it provides further support the discussion of poverty and food insecurity in Guatemala. Loewe, Ron 2009 Maya Reborn. Reviews in Anthropology 38:237-262. Loewe discusses the cultural revitalization movements of the Maya through the renewal of Maya theater in Chiapas, to promote spoken Maya in Guatemala, to excavate new ruin sites in Yucatan, and to revive Maya literature, music, and dance in all three areas. He provides many academic sources to support his thesis about the importance of cultural identity to the Maya people in Guatemala. This article expands on the importance of cultural identity in light of the global economy and its impacts on Guatemalan culture and politics. Mcllwaine, Cathy and Caroline Moser. 2003 Poverty, violence and livelihood security in urban Colombia and Guatemala. Progress in Development 3(2):113-130. Mcllwaine and Moser examine the poverty, violence and livelihood security in urban Colombia and Guatemala—and I will extract information about the Guatemala sections. They examine the physical and personal security for the individual living in these two countries, which can manifest in the form of violence and conflict for personal protection. They argue that it is important to focus on the overall human security at the micro-level. They discover from inductive participatory urban appraisal data that violence and physical safety are the main concerns of the poor, more than income poverty. Yet, all three variables often interrelate in the eyes of the poor. This article provides scholarly data research and further the discussion on poverty in Guatemala. 17 The PRS Group, Inc. 2014 Political Risk Yearbook: Guatemala Country Report. Political Risk Services 1-50. This is a country report of Guatemala provided by the Political Risk Services, LLC. It projects the political and economic conditions in Guatemala for 20142018. All information is compiled by the group based on their consistent research and reports of the country since their involvement in 1985. The economic projections include the gross domestic product (GDP) growth, inflation and current account status for the period. It examines three potential political regimes: a divided government, a center-right coalition and a two-right-wing coalition; they look at the international investment and trade risks under these three parties. In this end-of-the-year 2013 report, they also look back and analyze the security and social conditions, political structure and economic performance of Guatemala from 2003-2012. This is an important document as it provides up-to-date information about the government and economic conditions of Guatemala. It looks at all the possible political powers, providing an unbiased examination of the country’s political future. Rasch, Elisabet Dueholm 2011 Representing Mayas: Indigenous Authorities and Citizenship Demands in Guatemala. Social Analysis 55(3):54-73. This article strictly looks at the relationship between indigenous authorities in Guatemala with the larger context of indigenous claim in Latin America. While it doesn’t touch base on economy, this article reflects the continuous fight of indigenous identity recognition in Guatemala. The author argues that the indigenous individual puts personal meaning to their broader citizenship role in the Guatemalan state. Her investigation of the election of Quetzaltenago’s first Maya mayor and the abolition of part of the system of community services in Santa Maria are used in this article to put a framework of the indigenous approach to the construction of the broader national citizenship. This article reflects the strong sense of indigenous identity in Mesoamerica and the influence it plays on their political battles for political rights. 18 B: Pre-viewing Questions 1) How has issues of poverty and food insecurity affected the Castro family? 2) What does the Castro family do to survive in Guatemala’s economy? 3) How has the Castro family been able to preserve their cultural identity in Guatemala’s push for a globalized economy? C: Post-viewing Questions 1) What is the significance of the economic role of women in the Castro family and in the broader Maya culture? 2) What does weaving textiles symbolize for the Castro family and for the broader Maya culture? 3) What function does a Maya household have in dealing with issues of poverty and food insecurity? How does the Castro family represent this function?