The Sounds of Poetry

advertisement

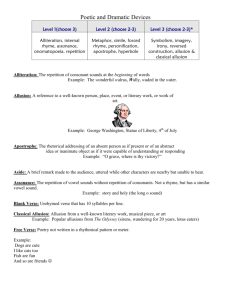

The Sounds of Poetry The Word Plum Helen Chasin The word plum is delicious pour and push, luxury of self-love, and savoring murmur full in the mouth and falling like fruit taut skin pierced, bitten, provoked into juice, and tart flesh question and reply, lip and tongue of pleasure. Sound is like any other poetic device. Good poems use them to further convey meaning. Our job as readers and reciters of poetry is to listen and hear the sounds to reinforce content. Reading the “The Word Plum,” how does the sound of the poem? Below are some terms to help you discuss what you notice about how a poem “sounds.” Definitions are from the Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms unless otherwise noted. Alliteration: The repetition of the same sounds—usually initial consonants of words or stressed syllables—in any sequence of neighboring words: “Landscape-lover, lord of language” (Tennyson). Now an optional and incidental decorative effect in verse or prose, it was once a required element in the poetry of Germanic languages (including Old English and Old Norse) and in Celtic verse (where alliterated sounds could be regularly be placed in positions other than the beginning of a word or syllable). Such poetry, in which alliteration rather than rhyme is the chief principle of repetition, is known as alliterative verse; its rules also allow a vowel sound to alliterate with any other vowel. Skillful poets use alliteration to intensify effects, add weight to an idea, and dare we say make the verse easy to remember. It can also make a poem sound childish. The important questions are: how is the poet using it; for what effect; and how does it help further convey meaning? Assonance: The repetition of identical or similar vowel sounds in stressed syllables (and sometimes in the following unstressed syllables) of neighboring words; it is distinct from rhyme in that the consonants differ although the vowels match: sweet dreams, hit or miss. As a substitute for rhyme at the ends of verse lines (sometimes called vowel rhyme or vocalic rhyme) had a significant function in the early Celtic, Spanish, and French versification, but in English it has been an optional poetic device used within and between lines of verse for emphasis or musical effect, as in these lines from Tennyson’s “The Lotos-Eaters”: And round about the keel with faces pale, Dark faces pale against that rosy flame, The mild-eyed melancholy Lotos-eaters came. Consonance: The repetition of identical or similar consonants in neighboring words whose vowel sounds are different (e.g. odds and ends, struts and frets). The term is most commonly used, though, for a special case of such repetition in which the words are identical except the stressed vowel sound (group/grope, middle/muddle, wonder/wander); this device, combining alliteration and terminal consonance, is sometimes known more precisely as “rich consonance,” and is frequently used in modern poetry at the ends of verse lines as an alternative to full rhyme. Consonance may be regarded as the counterpart to assonance. Onomatopoeia: The use of words that seem to imitate the sounds they refer to (whack, fizz, crackle, hiss); or any combination of words in which the sound gives the impression of echoing the sense. This figure of speech is often found in poetry, sometimes in prose. It relies on conventional associations between verbal and non-verbal sounds than on the direct duplication of one by the other. Cacophony: a harsh, unpleasant combination of sounds or tones. It may be an unconscious flaw in the poet’s music, resulting in a harshness of sound of difficulty of articulation, or it may be used consciously for effect. A poet may use the unpleasant sounds of a cacophony to communicate or evoke negative emotions such as disgust, distress or fear. It may also consist of “nonsense” words that cause discordance of sound and awkward alliteration. Harsher sounds include the "plosives" (b, d, hard g, k, p, t) (mrsbraman.files.wordpress.com) Euphony: a style in which combinations of words pleasant to the ear predominate; opposite of cacophony. Euphony is used by poets to bring about pleasant, peaceful feelings in the reader. It puts the reader at ease and makes the poem or piece of literature enjoyable to read. Long vowels are used in euphony because they are more melodious than consonants and short vowels; the enunciation and pronunciation are easy and agreeable. Though all vowels tend to be more melodious than consonants, long vowels (e.g. "moon," "coat," "crate,") resonate in the ear more than the short vowels found in "hat," "tin," "fun," "shed," or "hot.” Consonants that are fairly euphonious: The "liquids " (l, m, n, r) Soft f or v sounds The semi-vowels w or y Th or wh (mrsbraman.files.wordpress.com) Rhyme: The identity of sound between syllables or paired groups of syllables, usually at the end of verse lines; also a poem employing this device. Normally the last stressed vowel in the line and all sounds following it make up the rhyming element: this may be a monosyllable (love/above—known as a masculine rhyme), or two syllables (whether/together—known as a feminine rhyme or double rhyme), or even three syllables (glamourous/amourous—known as triple rhyme). Although rhyme is most often used at the end of verse lines, internal rhyme between syllables within the same line is also found. Rhyme is not essential to poetry: many languages rarely use it, and in English it finally replaced alliteration as the usual patterning device of verse only in the late 14th century. A writer of rhyming verse may sometimes be referred to despairingly as a rhymester or rhymer. Rhythm: The pattern of sounds perceived as the recurrence of equivalent ‘beats’ at more or less equal intervals. In most English poetry, an underlying rhythm (commonly a sequence of four or five beats) is manifested in a metrical pattern—a sequence of measured beats and ‘offbeats’ arranged in verse lines and governing the alternation of stressed and unstressed syllables. While metre involves the recurrence of measured unit sounds, rhythm is a less clearly structured principle: one can refer to the unmeasured rhythms of every day speech, or of prose, and to the rhythms or cadences of non-metrical verse.