Identities in the Warp Zone (Hamman & Shedrow, 2015)

advertisement

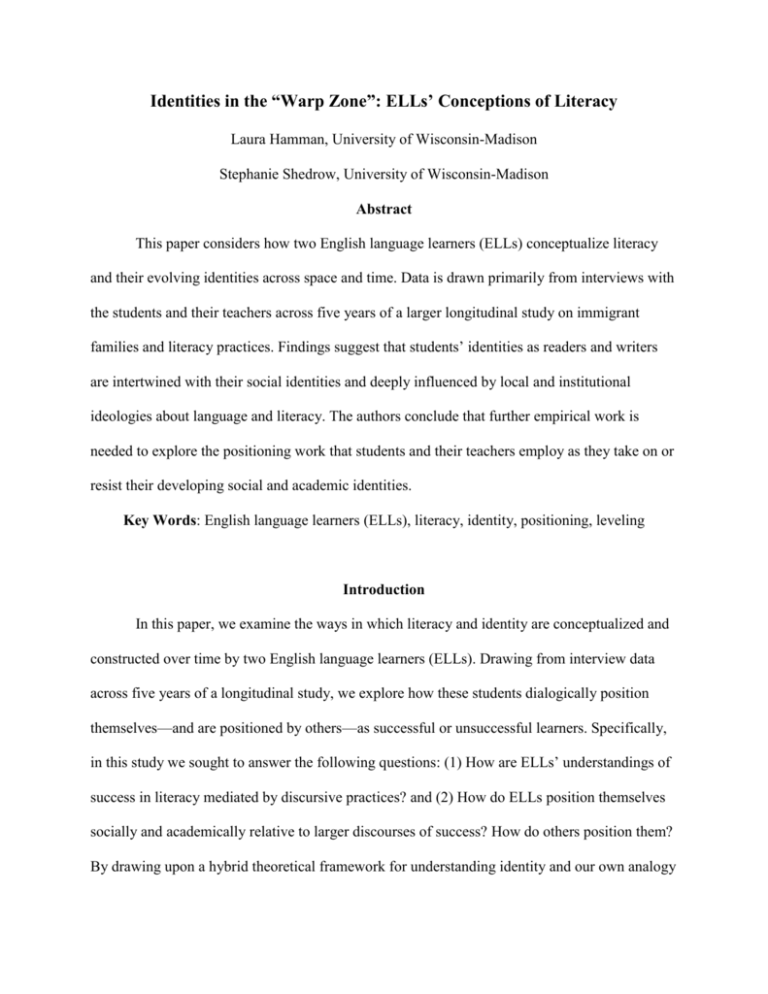

Identities in the “Warp Zone”: ELLs’ Conceptions of Literacy Laura Hamman, University of Wisconsin-Madison Stephanie Shedrow, University of Wisconsin-Madison Abstract This paper considers how two English language learners (ELLs) conceptualize literacy and their evolving identities across space and time. Data is drawn primarily from interviews with the students and their teachers across five years of a larger longitudinal study on immigrant families and literacy practices. Findings suggest that students’ identities as readers and writers are intertwined with their social identities and deeply influenced by local and institutional ideologies about language and literacy. The authors conclude that further empirical work is needed to explore the positioning work that students and their teachers employ as they take on or resist their developing social and academic identities. Key Words: English language learners (ELLs), literacy, identity, positioning, leveling Introduction In this paper, we examine the ways in which literacy and identity are conceptualized and constructed over time by two English language learners (ELLs). Drawing from interview data across five years of a longitudinal study, we explore how these students dialogically position themselves—and are positioned by others—as successful or unsuccessful learners. Specifically, in this study we sought to answer the following questions: (1) How are ELLs’ understandings of success in literacy mediated by discursive practices? and (2) How do ELLs position themselves socially and academically relative to larger discourses of success? How do others position them? By drawing upon a hybrid theoretical framework for understanding identity and our own analogy IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 2 of the “Warp Zone,” we explore the multilayered yet locally situated nature of identity positioning around literacy. A Hybrid Approach to Identity Theorizing Our theoretical framework merges three different understandings of identity to explore the productive dialogue within and between the approaches, namely, positioning theory, laminations, and Discourses. This fusion foregrounds individuals’ discursive negotiations with others and the world, and argues that these micro-level interactions cannot be understood without a critical consideration of the larger social, historical, and cultural contexts within which these interactions are (dialogically) embedded. We, thus, draw upon positioning theory as our central conceptual lens, but situate our understanding of identity-as-positioning within broader theoretical frameworks of culture and language stemming from sociolinguistics, linguistic anthropology, and cultural psychology. In our framing of identity, we also follow recent moves by poststructuralist scholars to move away from dominant Western humanist notions of identity as an essential, fixed core of an individual and, instead, understand identity as “subjectivity,” which captures the idea that an individual can be both the subject of a set of relationships and subject to a set of relationships, depending on her positioning and the power dynamics at play (Butler, 1997; Weedon, 1987). As Foucault (1980) has argued, these “subjectivities” are discursively constructed and always socially and historically embedded. We believe the theoretical framings of identity as positioning and as ‘subjectivity’ are complementary; accordingly, our use of a positioning theory lens embodies these same understandings. Positioning theories seek to explain how particular identities become embodied or rejected, as well as the impact of embodiment or rejection of an identity on one’s understanding of self over time (Moje & Luke, 2009). As originally theorized by Davies and Harré (1990), IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 3 positioning theory posits that identity construction is constantly in flux: “the whole of the ‘apparatus’ must be immanent, reproduced moment by moment in conversational action and carried through time, not as abstract schemata, but as current understandings of past and present conversations” (p. 55). Here, social positions are extended to individuals within distinct relations of power and, once afforded a position, an individual may take it up--in part or whole--or reject it (Bourdieu, 1977; Davis & Harre, 1990; Holland & Leander, 2004). To use Halliday’s (1985) language, a positioning lens considers the interrelationship of the “field” (topic), “tenor” (relationship between speakers), and “mode” (channel of communication), affording agency to both speakers in the active construction of identities while acknowledging that all identities are not available to all people. While positioning theory is a fruitful framework for identity construction, many recent applications of positioning theory have rejected its “imminentist ontology,” in which positioning becomes bound to the moment of interaction, as opposed to across interactions (Anderson, 2009). In order to better conceptualize identity as formed through moment-to-moment interactions yet also retain some constancy across interactions, we draw upon Latour’s (1993) analogy of “laminations.” According to Latour, laminations are identity positions layered on top of one another, thickened over time as a person takes on new subject positions. Considering positionality through a multilayered, laminated framework provides us with a more nuanced understanding of how individuals’ situated “bids” for identity (Hawkins, 2004) are part of their ongoing construction of identities. At the same time, the concept of laminations has been critiqued for not accounting for individuals’ different identities across time and contexts—in essence, the laminations become a “unified block” as new positions are added atop one another IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 4 (Moje & Luke, 2009). A more fluid understandings of laminations is needed to understand how and why individuals do not embody all of their laminations all of the time. Thus, to contextualize both identity as positioning and laminated, we consider how individual identities intersect with, shape, and are shaped by group or community identities, drawing upon Gee’s (1996) conceptualization of “Discourses” to illuminate this point. According to Gee (1996), big ‘D’ Discourses are distinct from the “little-d” discourses that represent everyday linguistic and communicative practices while the former refers to the intersection of language practices and group membership, a set of “saying(writing)-doing-being-valuingbelieving combinations” or “ways of being in the world” (p. 127, emphasis in original). Thus, in this paper, we consider both the everyday circulating discourses as well the Discourses that act as “identity kits” for certain social groups or categories. Extending this notion to positioning theory, it becomes clear that “Discourses” shape how individuals can and do position themselves—and are themselves positioned—within moment-to-moment interactions. Additionally, undergirded by an understanding of Discourses as socially, culturally, and historically constructed, positioning theory can then inform how individuals actively construct multilayered identities within the broader context of available subject positions, of potential “ways of being in the world” (Gee, 1996, p. 127). In joining these theoretical approaches to understanding identity, we propose a more nuanced understanding of the complex ways in which immigrant children come to ‘see’ themselves and be ‘seen’, relative to available school discourses and “Discourses” about literacy. In this way, we are better able to consider how immigrant children come to appropriate certain identities and not others, to become certain “kinds of people” (Hacking, 1986) within the spectrum of available subject positions. Additionally, we are able to consider the mutually IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 5 constitutive relationship between multiple, complex identities and existing “Discourses,” including how they interact and are maintained across space and time. Identities in the “Warp Zone”: A Heuristic In our search for a conceptual frame to better understand the patterns we were observing in the data—that is, the complex ways in which students and their teachers explored what it means to be a ‘good’ reader, writer, or student—we stumbled upon a helpful metaphor. And, as with many moments of clarity, it began with a conversation about our own experiences. In our discussion of the rich multimodal literacy practices of the two focal students, we began to reflect upon the gaming experiences of our youth and, in particular, the nuances of the video game Super Mario Brothers III. As we discussed the game, we began to see how our understandings of the identity and literacy practices and perspectives of the focal students and their teachers could be mapped onto one multi-dimensional space: “Warp Zone.” In the Super Mario Brothers III, the “Warp Zone” is a hybrid space where Mario can travel achronologically between game levels through a series of interconnected tubes. In order to enter this space, Mario must first find a flute that transports his character to the “Warp Zone,” where he, then, can choose which tube, or game ‘world’, he would like to enter. We liken these tubes and accompanying game worlds of the “Warp Zone” to the varying “Discourses” in which individuals engage, which, in turn, develop their capacities to become certain ‘kinds of people’. Applied to education, these ‘game worlds’ become the available discursive spaces through which students can engage with certain Discourses—or not. Importantly, only certain ‘worlds’ are available for play within any given level. Likened to contemporary U.S. schooling, there are particular ways of being a “good” student and of becoming a “successful” reader or writer that are available for ‘play’. Importantly, these Discourses are shaped not only by local, situated IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 6 practices and beliefs of individual teachers and students but also by larger institutional and societal forces. Thus, if literacy in school spaces becomes defined through the neoliberal lens of high-stakes assessment and measurable progress, students must engage with those framings if they want to become—and be understood as—competent or successful readers and writers. The “Warp Zone” metaphor also reveals that, like Mario operating within the confines of the game, individuals are limited in their ability to access certain identity positions: not all identities are available for all people. That is not to say that Mario is without agency. He is able to choose which ‘world’ to enter and employs his unique set of skills and resources to play the game in the form of his choosing; however, Mario is also constrained by the available options. For example, in Super Mario Brothers III, some ‘worlds’ provide tools for Mario to navigate with greater ease. For example, in one level, Mario can access fireballs that help him advance through the level and conquer the villains. However, these fireballs would not—and cannot—be leveraged in every game world (such as the underwater world where fire would be rendered useless). Likewise, students access certain tools to be seen as ‘successful’ readers and writers at school, such as the attainment of a particular standardized reading score and engaging in ‘appropriate’ writing practices and conventions, but these school-based tools many not be helpful for understanding or practicing literacy in other spaces. Additionally, while Mario retains his ‘laminated’ skill set across worlds, his multifaceted abilities are valued in all spaces of the game. For example, his ability to jump is not a strength within the underwater level, while that same skill is essential to surviving the cloud world, where he must hop between clouds to stay alive. Similarly, as we came to learn through this study, immigrant students’ range of linguistic repertoires are not valued and validated in all spaces. For instance, in a bilingual classroom, the minority language is generally viewed as an asset and, for IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 7 many immigrant families, bilingual children’s “language brokering” skills may be essential to the family’s participation with the wider community (Orellana, 2009). However, within a monolingual, English-only classroom, speaking a minority language is often viewed through a deficient lens or simply dismissed as unnecessary. We believe that the “Warp Zone” metaphor helps capture the inherent tension between agency and constraint and its intimate relation to identity positioning. Like Mario, immigrant students have agency in choosing to ‘play’ or ‘not play’ the available schooling and literacy Discourses; at the same time, only certain ‘worlds’ are available for play. Furthermore, when playing the game, certain aspects of students’ multilayered identities are more or less valued. Thus, enacting literacy within school spaces carries with it certain discourses and certain ways of playing the game with students as agentic players; however, in order to win, they must be willing to enact and take on certain ways of being a student and of doing literacy. We offer this “Warp Zone” example, then, not as a new theoretical model for identity, but, rather, as a metaphor or heuristic for better conceptualizing (1) the tension between agency and constraint, (2) the ways in which certain skills or abilities are recognized in different spaces, and (3) the ways in which individuals come to embody certain Discourses. These notions will be further explored in our analysis and discussion of our findings. Methodology The data for this study has been extrapolated from a larger, longitudinal qualitative study which seeks to understand identity and literacy development for children in immigrant families across home, school, and community spaces over an extended time (see Compton-Lilly et al., 2015). For this paper, we highlight two of the fifteen focal children and draw principally from the interview data from the two boys and their teachers across five years of schooling. Felipe IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 8 Hernandez and Carlos Gomez, currently in sixth and seventh grade respectively, were selected as focal participants for this current paper because both students (1) are Mexican-American boys in middle school, and (2) have been repeatedly positioned as successful readers and writers during data collection across this longitudinal research project. Participants Felipe, born in Veracruz, Mexico, migrated with his parents to the United States when he was two-years-old. Manuel, Felipe’s father, worked as a florist in Mexico and found the same employment in the United States. Upon moving he was able to quickly glean English from his fluent coworkers and customers at the floral shop. Felipe’s mother, Rosi, has worked various jobs during the course of the study, including in-home cleaning and babysitting. Rosi struggled to learn English and began taking English classes offered at the local community college. Since moving to the United States Manuel and Rosi have welcomed two additional children into their family, Violet (currently in third grade) and Gabriel (currently in first grade). Violet and Gabriel have not yet visited Mexico, and Felipe has yet to return since migrating here as a child. As such, he often needs assistance from his parents in recalling people or places. Carlos’s family also migrated to the United States from Mexico, though he was born in the country shortly after their arrival. Carlos’s father, Juan, works long hours on evenings and weekends as a chef at Chili’s and has been able to learn some English on the job. Vilma, Carlos’ mother, does not work outside the home and, while she has taken some English courses from the local community college, she has limited English and prefers to conduct interviews in Spanish. Amanda and Benjamin, Carlos’ younger siblings were also born in the United States and are now in first and second grade, respectively. Most of their extended family lives in Mexico, though Vilma’s sister has moved to the same U.S. town. While Carlos has only been to Mexico once (in IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 9 4th grade), both Vilma and Juan’s parents have come to visit the family in the U.S. for lengthy stays. Carlos’s family frequently communicates with their extended family through Skype and email, and Vilma often shares that she misses life in Mexico. Data Collection & Analysis In the larger study, three rounds of data collection occur annually. Solicited data includes semi-structured interviews with the student, a parent, a family member, and a teacher; annual reading assessments; student artifacts (drawings and photographs); and classroom, home, and community observations (see Table 1 below). All collected data is then coded deductively and inductively using the qualitative software Nvivo. For the current study, codes such as “child reading,” “child writing,” “home literacy,” “school literacy,” and “technology” were pulled for analysis. Table 1: Data Collected by Round Interviews Round 1 (September/ October) Student Parent Teacher Artifacts Round 2 (December/ January) Round 3 (May/June) Student (incl. discussion of photos from round 1) Family member (other than parent from Round 1) Student (incl. discussion of photos from round 2) Parent Teacher Observations Student self-portrait with written description Student-created map of neighborhood and school with written descriptions Student-taken photos of neighborhood & school Researcher administered reading assessment Student-created picture of his/her native country with written description Student-created map of home with written description Student-taken photos of home 10 student-selected images from Internet with recorded discussion Researcher-administered reading assessment Final school-issued report card In-home observation School observation of literacy class In-home observation Observation of student with family at community event In-home observation School observation of literacy class IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 10 Findings and Discussion Measuring Success The ever-swelling neoliberal ideology that has shifted the blame for economic inequalities onto the education system is creating new Discourses within educational contexts that are being utilized to discuss teaching and learning (Hursh, 2007). Foundationally, the neoliberal education agenda is twofold. First is the marketization and commodification of educational systems where, rather than citizens, individuals are consumers of services (Davies & Bansel, 2007; Lipman, 2011). This notion has been supported by the argument that parents and students are not powerful enough to have a voice within educational systems, but, by allowing them to be ‘consumers’ who select their educational provider, a natural selection will take place and unpopular schools will change or close (Chubb & Moe, 1990). The second hand of neoliberal reform is the process of implementing accountability measures and performance goals (Davies & Bansel, 2007). As Apple (2006) explains, choice and privatization of educational systems cannot happen without a systematic rollout of learning ‘standards’ and performance assessments. He notes, “...paradoxically a national curriculum and especially a national testing program are the first and most essential steps toward increased marketization...Absent these mechanisms, there is no comparative base of information for ‘choice’” (Apple, 2006, p. 71). With the rollout of the Obama administration’s Race to the Top, we have witnessed the push for national curriculum and assessments (“Fact Sheet: Race to the Top,” 2009), as well as the unfolding of the marketization and commodification of the public educational sector by private entities. Quantifying success. Educational reforms such as No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top have reshaped what it means to be a successful reader and writer for K-12 students. These IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 11 ‘one and done’ assessments have created a testing frenzy as teachers, schools, and districts prepare for the definitive exams (Manna, 2011), resulting in a “leveling mania” in elementary classrooms (Dzaldov & Peterson, 2005). Our findings indicate that students are not exempt from these pedagogies, and, in fact, are often encouraged to know and understand their reading level. This may best be illustrated by our study participants’ answers to the following interview questions asked annually during our second round of data collection: (1) “Are you a good reader? How do you know?” and (2) “Are you a good writer? How do you know?” Carlos, who became a study participant when he was in second grade, views himself as a successful reader most notably because this position has been offered to him through testing and accountability measures. In second grade, when asked if he was a good reader Carlos responded, “I don’t know, but in English I’m level 20 and then Spanish level 25.” Here we can see that Carlos understands that his reading is associated with a ‘level,’ yet he does not yet know what this means. However, just one year later, Carlos responded to the same questions by answering, “The highest level to read is 30 and I’m at that level.” By third grade, Carlos not only equates his reading abilities with a score, but also understands that his score falls on a continuum—and at a point that positions him as a ‘good’ reader. As Carlos’s reading skills advance, his understanding of reading ‘levels’ also becomes more nuanced and less about finite scores. For example, in fourth grade Carlos noted, “I read [at] a middle school [level].” At this point Carlos has made the cognitive leap from abstract scores to grade level equivalencies. As a fourth grader, Carlos has been positioned as as student who reads at a ‘middle school level,’ a position which Carlos easily interprets to mean that he is, indeed, a successful reader. By sixth grade, when asked why he thinks he is a ‘good’ reader, Carlos clearly articulates his abilities by stating, “[Be]cause my teachers, when they like hear me read they say IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 12 I read good. Like good tone. Well, they don’t give me, like, the grade like it is. They give me one year grade ahead of reading and still, like, read good.” Thus, even in the fifth year of data collection, Carlos reports his reading ‘success’ through his teachers’ feedback and, specifically, in where he falls on the continuum of leveling—and Carlos willing accepts this position. We can see a similar pattern with both Carlos and Felipe when it comes to their writing abilities. In first grade when asked “Are you a good writer?” Felipe enthusiastically responded “Yeah!” After the follow up question regarding how he knows that he is a good writer, Felipe offers, “[I] can write a story about Chuck E Cheese with seven pages.” This response makes it unclear if Felipe was explicitly offered this position as a ‘good writer’ by teachers because of quantification, but it is evident that Felipe associates length of writing to writing abilities. Five years later, when in fifth grade, Felipe maintains this understanding of what it means to be a good writer. Here, when asked about his abilities, Felipe notes that he is merely “So-so” because he only adds details to his writing when allowed to type it. While considering “details” illustrates Felipe’s increasingly complex view of ‘good’ writing, adding details also inherently connects to page length. Similarly, Carlos equates his writing abilities to the quantifiable amount he is able to produce. In third grade, Carlos justifies that he is a ‘good’ writer by stating, “I write like two, a-, two full pages.” In sixth grade, Carlos notes that he is a good writer because he gets good grades. As with Felipe, it is conceivable that, for Carlos, the association between volume of writing produced and being a ‘good’ writer was a position offered by teachers; but, later, Carlos has clearly been offered, and accepted, the position of being a ‘good’ writer because of the grading marks he receives. IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 13 Taken collectively, the juxtaposition of the two boys’ responses as to why they are ‘good’ readers or writers highlights how the neoliberal agenda has infiltrated reading instruction, perhaps more so than writing instruction. As reading is easier to quantify in multiple choice assessments and leveled texts, it is not surprising that the students in this study were able to more clearly articulate their leveled reading score while only able to align their writing to the number of produced pages. Unexpectedly though, neither student, across five years of data collection, mention the ‘needs improvement,’ ‘approaching,’ ‘proficient’ or ‘advanced’ scale commonly employed to evaluate student writing. Qualifying success. As noted above, policies begin to infiltrate educational discourses and Discourses as they move through districts and schools, and, finally, into the culture of individual classrooms (Lipman, 2004). These ideological discourses become normalized, creating structures of meaning that shape available Discourses of “successful” students, as well as operationalizing as statements of value (Ball, 1990). In addition to quantifying success, our findings elucidate how neoliberal values enable teachers to position students through qualifying statements regarding their abilities or the subjective analysis of assessments as predictors of success. For example, Felipe’s accelerated reading skills were often downgraded because of peripheral factors. During the second year of data collection Felipe’s teacher noted although Felipe’s reading scores place him as ‘advanced,’ she considers him as only “high average” because “it’s really easy to be advanced, like, everybody is advanced in this class, almost, expect for like the special ed[ucation] kids.” In this example, although Felipe’s scores indicate his achievement in literacy, his teacher qualifies them through a neoliberal discourse of competition; thus, if everyone scores ‘advanced,’ the test must be flawed. Felipe’s teacher, then, does not IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 14 position Felipe with the label of an ‘advanced’ student—which, perhaps, restricts him from being enrolled in Gifted and Talented or placing him in a ‘higher level’ reading group. Additionally, at the English-only school, Felipe’s academic success is frequently understood—and qualified—through an ELL framing. For example, when asked about Felipe’s writing abilities, his first grade teacher commented: Well, I think he actually has a pretty good idea of what he wants to write about. I don’t he, he pushes himself to his full potential, and I don’t know if it’s because he has the story in his head in Spanish, but when he goes to write the English words he has trouble... Thus, while the teacher acknowledges Felipe’s skill with brainstorming story plots, she frames his Spanish as a limitation to his writing production. In this same interview, she also highlights the negative transfer of grammatical structures from Spanish to English, a deficit perspective of Felipe’s Spanish abilities that ignores the myriad ways in which Spanish might serve as a bridge to his literacy development in Spanish, as empirically documented by numerous scholars (Bialystok, 2006; Cummins, 1979; Gort, 2006; Pérez, 2004). Across a year of interviews with this teacher, Felipe is continually positioned as a successful writer but always with the qualification of him being a non-native English speaker. She explains, “I think, given the fact that he is an ESL, he does great,” and “For an ELL kid, that’s a lot of progress to make in a year.” While more common for Felipe in an English-only school, Carlos, too, was positioned as successful within the framing of being a non-native speaker. In one interview, His teacher explains, “He had really great vocabulary in English so I was very impressed, um, because I knew he was a native Spanish speaker.” It is interesting that Carlos also experiences this form of qualifying his reading and writing skills since, at that time, he was enrolled in a prestigious and successful dual language immersion program that endorsed additive bilingualism (Lambert, IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 15 1975), viewing Spanish both as an asset towards learning English and as a language to be maintained and developed. These findings suggest that deficit-based ideologies of bilingualism are difficult to subdue, even in a program that privileges the minority language. Theoretical applications and discussion. In many of the examples above, such as the participants’ tendency to quantifying their reading and writing abilities or Felipe’s second grade teacher withholding the position of ‘advanced’ from him, Latour’s (1993) analogy of “laminations” is an excellent means of elucidating how identities, as positions, are layered atop one another and solidified over time. Across the study, both boys continuously recounted that they were good readers and writers, thus adopting and internalizing particular identity positions that were made available to them, though understanding them within the available neoliberal and educational discourses of “success.” Additionally, “laminations” can help explain why Felipe never, during five years of data collection, discussed his abilities (in literacy or elsewhere) as ‘advanced.’ Because this position was withheld from him it never became a lamination. That is, it never had time to seep into the fabric of Felipe’s identity, even though he is—as demonstrated by the bi-annual reading assessments administered by researchers in this study—an advanced reader. Additionally, across five years of schooling, both boys’ literacy abilities were understood through—and limited by— an “ELL” lens. This understanding of their reading and writing abilities still allowed the boys to take on successful academic identities, but restricted their reach. The Warp Zone analogy illuminates this positioning work, as both boys were able to successfully ‘play’ the academic game, but had to do so in ways that were legitimized by the school and that ignored some of their linguistic abilities, such as Felipe’s Spanish in a monolingual English-only school. Thus, Carlos and Felipe had some agency in choosing whether or not to engage with the IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 16 available Discourses of being a “successful” reader or writer, but were limited by the ‘levels’ available for ‘play’ and could only enact those identities if they were willing to be positioned in particular ways, and to let some of their selves go unseen. Complex Social & Academic Identities Longitudinal work provides the unique vantage point of tracking change over time. Accordingly, as we analyzed parallel interview data across five years, we were able to observe change and maintenance in how both Felipe and Carlos were positioned—and positioned themselves—across school, home, and community spaces. One important finding from our analysis was that both boys were never solely positioned as readers or writers based on academic progress; rather, social identities and interests came to play an important role in how they came to be seen as learners. This finding corroborates Wortham’s (2006) argument that students’ social identities are intertwined with their academic learning, such that one cannot be understood without the other. Shifting and overlapping identities. Across five years of schooling, Carlos was frequently positioned as “immature,” which came to bear on teachers’ understandings of him as a student and as a reading and writer. His third grade teacher explains, “Um, [Carlos] gets along well with others. He's a little bit immature, even for somebody who's a year younger than the rest of the 3rd graders...but he's a very solid worker.” However, when considering Carlos’s writing, the same teacher recounts, “Um...he writes about his own life in a very meaningful way...It’s um incredibly mature, which is curious because behaviorally he’s pretty immature compared to everybody else...So it surprises me that he has that in his writing.” In this example, Carlos’s writing abilities are understood through the consideration of his social identity as an “immature” student. Across five years of data collection, Carlos was continually positioned as immature, yet IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 17 simultaneously recognized as a successful student. This highlights the interrelationship between students’ academic and social identities and, furthermore, how academic ‘success’ might be shaped by the social people that teachers see their students to be. Felipe’s academic and social identities also come to bear on each other. In second grade, Felipe’s teacher recalled that, after reading a book about autism to the class, Felipe remarked, “Oh, I need some autism [be]cause then I can pay better attention!” She elaborates upon this comment by stating: I think he does kind of have attention issues but I always remind myself he’s really a first grader in age, which is what helps me to think, you know, it’s kind of the problem with people who move here from other places with different…they are going to be put in classes, like he got put in a class ahead of where he should have been age wise. And he would have fit way better in a class below. While Felipe was reading ‘above grade level,’ his teacher positioned him as immature and suggested that he was placed in the wrong grade-level even though Felipe had attended the same school since kindergarten. What is interesting about this positioning is that it not only recurs throughout the five years of data collection, but is also always collocated with Felipe’s positioning as a leader (or bully) in his class. For example, in third grade Felipe is positioned by his teacher as a leader, as someone who looks out for his friends. During this interview, Felipe’s teacher mentions that Felipe would read aloud to his male friends who were not as fluent in English. The teacher also notes that Felipe continuously reminded other students of the rules to help them self-monitor their behavior. However, the following year, Felipe was labeled by his teacher as a ‘bully.’ While the full extent of Felipe’s actions was not divulged to researchers, the teacher mentioned that he was “investigating a lot of different behaviors that were pretty cruel.” This reveals how social and academic identities not only overlap, but also shift across time, with certain characteristics taking IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 18 on different forms or being recognized in different ways. However, it is important to recognize that these shifts do not necessarily occur across all spaces. At the same time that Felipe was not exhibiting positive leadership qualities at school, his parents still perceived Felipe as a leader at home, as when he would read aloud to his siblings or translate English texts for his parents. Thus, the different, complex identities that students appropriate or are given—immature, leader, bully—are not static across time or space, nor are individuals without agency to accept or reject these positions. The shifting or reframing of social and academic identities is especially interesting in the context of moving from one school to another. For the first four years of the study, Carlos was at a public charter school with a successful dual language immersion (DLI) program that taught students to read and write in both English and Spanish. However, in the fifth year of the study Carlos advanced to a public middle school with only one ‘house’ (or strand) of DLI and four ‘houses’ of regular, monolingual classroom instruction. Thus, while Carlos still took classes in English and Spanish, having only a portion of the student population in a DLI program significantly impacted the linguistic climate. Carlos’s sixth grade English language arts teacher, shared an illustrative example of student language use from the DLI house’s camping trip that year: Ms. Fisher: ...we went to, on a two night overnight to Living Forest, stayed in cabins, exhausted ourselves, and at the end of the experience we have a circle where you can get up and stand in a special place and hold a candle and say a memory of what happened in Living Forest. So the teachers modeled it first. I went and spoke in English and Spanish language arts teacher went and spoke in Spanish, and then the math teacher spoke in English and then the science teacher spoke in Spanish. And we modeled every other. And then I’d say probably fifty kids from the house got up and every single one of them spoke in English. None of them spoke in Spanish. Even though I hear them in the hall. Like I don’t know, they just didn’t... IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 19 From this example, it becomes evident that the “symbolic dominance” (Bourdieu, 1991) of English within the wider school—and society—impacted how students chose to present their thoughts in public, even when among other bilingual students. When considering Carlos’s language and literacy practices, Ms. Fisher notes, “I don’t hear Carlos speak a lot of Spanish actually. I hear other people but not Carlos. I don’t know if he just covers it well...” From classroom observations, too, it became clear that Carlos was using less Spanish at the middle school than in his previous years in elementary school. Thus, the pervasive new local discourses appear to have influenced the ways in which Carlos positions himself academically, socially, and linguistically in the classroom. Nevertheless, regardless of how Carlos chooses to position himself, he is simultaneously being positioned within this new school environment. In fourth grade, Carlos’s teacher Ms. Earle described him as a successful reader in English literature circles, stating, “he is also a leader in that and that’s pretty cool to have a 4th grade leader in a 4/5 class.” However, in middle school, Carlos was not seen as a highly successful reader and writer, in part due to his ‘ELL’ status. Ms. Fisher was interviewed in November, more than two months into the academic year, yet she did not know much about Carlos’s reading abilities and, accordingly, had made some assumptions about them based on his ELL status. She explains that, at the beginning of the year she had put Carlos in a lower reading group but had since moved him up to the middle group. However, even then, she qualifies his grouping, explaining, “Middle is relative because they have a lot of students that are a little lower than grade level, which I think is typical in a DLI program…” In the structure of middle school, where educators teach each class for an hour or so on a given day, it takes longer for teachers to get to know their students. Someone who is quiet and compliant like Carlos can be overlooked. Unfortunately for Carlos, this led his teacher to rely on IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 20 assumptions and standardized test scores that framed him as an average, less successful reader. Interestingly, like Felipe, across the five years of this study, the researcher has used biannual reading assessments to evaluate Carlos’s English literacy skills, and Carlos has consistently shown that he decodes and comprehends above grade level. Recognition work. Across the five years of data collection, we learned that Felipe and Carlos shared many interests, such as reading graphic novels like The Diary of a Wimpy Kid series and playing video games. As we examined the ways in which the boys’ interests intersected with the literacy practices valued at school, we observed a profound dissonance. Felipe, in particular, took on a social identity that centered on his love for video games—seeing himself as a “gamer”—which took on different meanings across home and school contexts. At school, Felipe’s gaming interests were negatively framed in connection to his academic identity as a “struggling writer.” Commenting upon the brevity and content of his writing, Felipe’s first grade teacher remarked: Yeah, it is difficult for him to write about something that is not related to video games...I feel he uses Sonic and Mario because that is what he does. I bet you, when he’s a home, that’s what he does! However, at home, Felipe’s social identity as a “gamer” takes on more relevance for his literacy development as he frequently reads books about video games, and his parents often refer to him as a human “instructional manual” because of his knack for navigating the language of games. Interestingly, when asked about his reading and writing abilities Felipe—perhaps reflecting his teachers’ perspectives—did not connect the sophisticated literacy skills involved in gaming to his academic identity as a reader and writer. Similarly, Carlos shared that he and his friends often write and share imaginative stories about games they are playing, yet, across five IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 21 years of being asked if he was a writer, Carlos consistently turned to school examples as evidence for his affirmative answer. Another revealing insight was the difference that emerged between ‘writing’ and ‘being a writer’ in school discourses. In an interview, Carlos’s third grade teacher noted that he was successful in writing but, in her description, reveals that she did not consider him as a ‘writer’: Mmm, I mean he’ll do it, but he’s not like, one of those kids who’s like, “Can I take my writing notebook home tonight?”, or, “I wanna write about this”, or, you know what I mean?...Like, he doesn’t do anything above and beyond. And it’s hardly ever like, really revealing emotionally. Like some kids once in awhile, you’ll read something like, “Wow, I can’t believe you...you’re sharing that,” but he won’t, he’s not like that. According to this teacher, a ‘writer’ not only explores and shares deep feelings but also eagerly engages with school literacy opportunities, which include bringing school practices and artifacts (e.g., his writing notebook) into the home. She does not consider, or perhaps know, that Carlos and his friends engage in an active writing community outside of school, writing and sharing stories of their video game worlds. Like Felipe’s gaming activities, these literacy practices are not recognized by the school as ‘academic’, such that Carlos is able to position himself as a successful student in writing but not as a ‘writer’. Theoretical applications and discussion. From the examples highlighted, it is clear that Carlos and Felipe’s academic identities as readers and writers are intertwined with their social identities. In the interviews with teachers across time, both boys were seen as “immature,” one ‘lamination’ of their social identities that impacted the ways in which teachers understood their academic success. Their social identities, however, were not static; while immaturity may have been a consistent framing across time, Felipe experienced the shift from being seen as a leader to becoming a bully. His agency in taking on, or not, the positioning of classroom leader shows that Felipe had (some) control over his own school identity. Carlos, too, came to be seen differently IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 22 as he shifted across school spaces. As he moved from an all-DLI elementary school to a middle school with far fewer Spanish speakers, Carlos began to use less Spanish in academic settings. This finding builds upon other scholarly work by demonstrating how space shapes and organizes “regimes of language” (Blommaert et al., 2005) and, in this particular context, how English retains dominant status. The Warp Zone is a useful analogy here, too, for better understanding how social and academic identities intersect and overlap. In the fluid space of the Warp Zone, Mario is able to choose which ‘levels’ best match his interests and skills; however, not all levels require his full repertoire of abilities nor are all levels open to play. Similarly, across five years of interviews, Carlos and Felipe continually position themselves as successful readers and writers and their teachers (more or less) confirm this understanding; however, reading and writing are understood within the lens of schooling, which often ignores or illegitimates out-of-school literacy practices. Carlos and Felipe, then, come to see these practices as existing in separate spheres, as evidenced from neither boy referring to gaming or peer writing practices as connected to what it means to be a “good” reader or writer. Conclusion We conclude that a multifaceted theoretical lens and the analogy of the Warp Zone allow us to better understand how Carlos and Felipe come to see themselves as readers and writers, and how their teachers come to understand these proposed identities within the context of neoliberal values and local school discourses. Like Mario, Carlos and Felipe enter into the Warp Zone to travel through the interconnected tubes of their lives and embody various layered identity positions across different temporal and spatial contexts. The boys’ evolving, multilayered identities are taken up in different ways as they position themselves and are positioned as IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 23 successful or unsuccessful ELLs, “gamers,” and students. Furthermore, larger socio-historical discourses (“the game”) around language, literacy, and academic success impact the ways in which Carlos and Felipe position themselves across time socially and academically—and the ways in which they continue to be positioned. Positioning theory allows us to focus the conceptual lens on the interaction, on Carlos and Felipe’s individual agency and negotiation of social and academic identities; the consideration of laminations reveals how some identity positions become more stable across time, such as being an ELL or being immature, though these multiple layers are never fully fixed, as demonstrated from Felipe shifting from being a leader to a bully. Additionally, with a broader understanding of available “ways of being” or Discourses, we can see how Felipe and Carlos make (conscious and unconscious) choices about how they understand reading and writing and how they come to see themselves relative to available framings. As reading is often discussed in schools in connection to standardized scores and leveled books, students come to take on identities as readers within that framing. Likewise, both the boys and their teachers considered Carlos and Felipe to be successful writers, but only within the framing of school practices, ignoring the complex and creative literacy practices of gaming and creative writing that the boys employed outside of school spaces. We are left wondering at the affordances of this metaphor and accompanying theoretical framings of identity for other contexts: How do students learn to ‘play the game’ and what ‘game worlds’ are made available to them? Cope and Kalantzis (2009) contend: The kind of person who can live well in this world is someone who has acquired the capacity to navigate from one domain of social activity to another, who is resilient in their capacity to articulate and enact their own identities and who can find ways of entering into dialogue with and learning new and unfamiliar social languages (p. 173-174). IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 24 We agree, though we add that the navigation across fluid spaces never occurs without active positioning and is always somewhat limited by the available discourses and Discourses that frame how identities like “reader” and “writer” come to be constructed. We are in need of further longitudinal empirical work to continue to explore the complex ways in which immigrant students come to understand and enact literacy identities across space and time. IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 25 References Apple, M. W. (2006). Educating the" right" way: Markets, standards, God, and inequality. Taylor & Francis. Anderson, K. T. (2009). Applying positioning theory to the analysis of classroom interactions: Mediating micro-identities, macro-kinds, and ideologies of knowing. Linguistics and Education, 20(4), 291-310. Ball, S. J. (1990). Markets, inequality, and urban schooling. The urban review,22(2), 85-99. Bialystok, E. (2006). Bilingualism at school: Effect on the acquisition of literacy. In P. McCardle & E. Hoff (Eds.), Childhood bilingualism: Research on infancy through school age (pp. 107–124). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Blommaert, J., Collins, J., & Slembrouck, S. (2005). Spaces of multilingualism. Language & Communication, 25(3), 197–216. Bourdieu, P. (1977). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In J. Karabel & F. Halsey (Eds.), Power and ideology in education (pp. 487–511). New York: Oxford University Press. Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Butler, J. (1997). The psychic life of power: Theories in subjection. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Compton-Lilly, C., Kim, J., Quast, E., Tran, E. & Shedrow, S. (2015). Transnational practices in immigrant families. The Wisconsin English Journal, 57(2). Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2009). “Multiliteracies”: New Literacies, New Learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal (Vol. 4). IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 26 Chubb, J. E., & Moe, T. M. (1990). Politics, markets, and America's schools. Brookings Institution Press. Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 49, 222–251. Davies, B., & Bansel, P. (2007). Neoliberalism and education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 20(3), 247-259. Davies, B., & Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the theory of social behaviour, 20(1), 43-63. Dzaldov, B. S. & Peterson, S. (2005). Book leveling and readers. The Reading Teacher, 59(3), 222-229. Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, New York, Pantheon. Gee, J. P. (1996). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideologies in discourses. London: Taylor & Francis. Gort, M. (2006). Strategic codeswitching, interliteracy, and other phenomena of emergent bilingual writing: Lessons from first grade dual language classrooms. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 6(3), 323-354. Hacking, I. (1986) Making up people. In T.C. Heller, M. Sosna, and D.E. Wellbery (with A.I. Davidson, A. Swidler, and I.Watt), eds, Reconstructing individualism: Autonomy, individuality, and the self in Western thought. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 222-236. Halliday, M.A.K. (1985). Spoken and written language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” 27 Hawkins, M. R. (2004). Researching English language and literacy development in schools. Educational Researcher, 33(3), 14-25. Holland, D., & Leander, K. (2004). Ethnographic studies of positioning and subjectivity: An introduction. Ethos, 32(2), 127-139. Hursh, D. (2007). Assessing No Child Left Behind and the rise of neoliberal education policies. American educational research journal, 44(3), 493-518. Lambert, W. E. (1975). Culture and language as factors in learning and education. In A. Wolfgang (Ed.), Education of immigrant students: Issues and answers (pp. 55–83). Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. Latour, B. (1993). We have never been modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Lipman, P. (2004). High stakes education: Inequality, globalization, and urban school reform. Psychology Press. Lipman, P. (2013). The new political economy of urban education: Neoliberalism, race, and the right to the city. Taylor & Francis. Manna, P. (2011). Collision course: Federal education policy meets state and local realities. Washington, D.D.: CQ Press. Moje, E. B., & Luke, A. (2009). Literacy and identity: Examining the metaphors in history and contemporary research. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(4), 415-437. Orellana, M.F. (2009). Translating childhoods: Immigrant youth, language, and culture. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Pérez, B. (2004). Becoming biliterate: A study of two-way bilingual immersion education. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Weedon, C. (1987). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory. Oxford, UK: B. Blackwell. IDENTITIES IN THE “WARP ZONE” Wortham, S. E. F. (2006). Learning identity: The joint emergence of social identification and academic learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. The White House. Office of the Press Secretary. (2009). Fact Sheet: Race to the Top. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/factsheet-race-top. 28