Fiction and politics emag article

advertisement

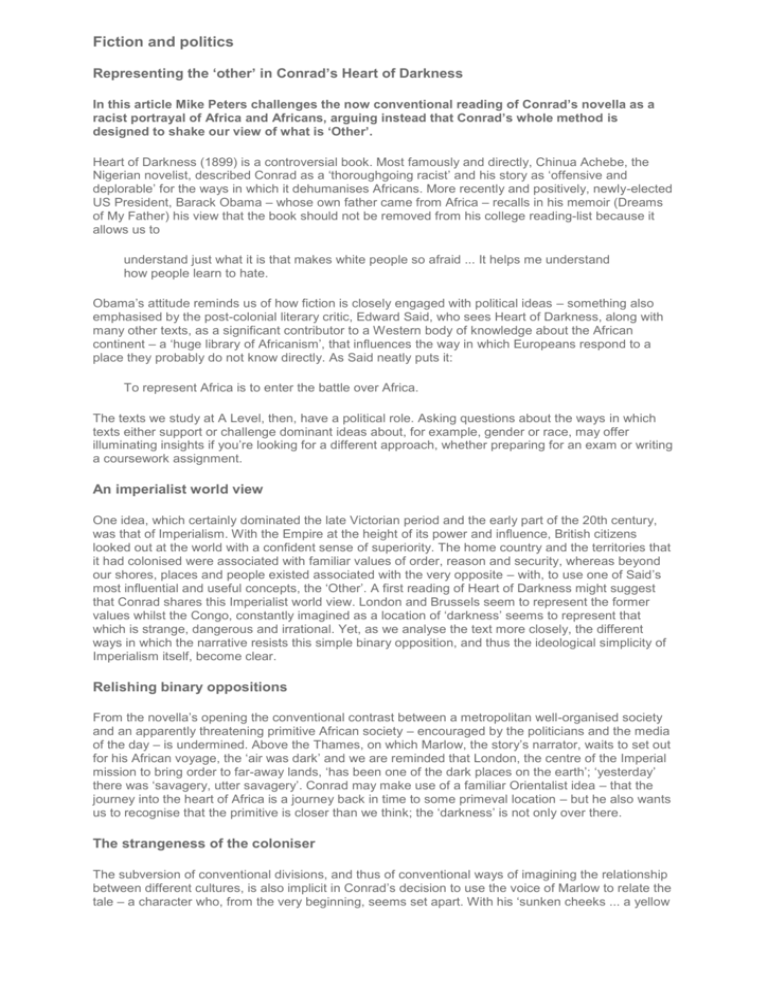

Fiction and politics Representing the ‘other’ in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness In this article Mike Peters challenges the now conventional reading of Conrad’s novella as a racist portrayal of Africa and Africans, arguing instead that Conrad’s whole method is designed to shake our view of what is ‘Other’. Heart of Darkness (1899) is a controversial book. Most famously and directly, Chinua Achebe, the Nigerian novelist, described Conrad as a ‘thoroughgoing racist’ and his story as ‘offensive and deplorable’ for the ways in which it dehumanises Africans. More recently and positively, newly-elected US President, Barack Obama – whose own father came from Africa – recalls in his memoir (Dreams of My Father) his view that the book should not be removed from his college reading-list because it allows us to understand just what it is that makes white people so afraid ... It helps me understand how people learn to hate. Obama’s attitude reminds us of how fiction is closely engaged with political ideas – something also emphasised by the post-colonial literary critic, Edward Said, who sees Heart of Darkness, along with many other texts, as a significant contributor to a Western body of knowledge about the African continent – a ‘huge library of Africanism’, that influences the way in which Europeans respond to a place they probably do not know directly. As Said neatly puts it: To represent Africa is to enter the battle over Africa. The texts we study at A Level, then, have a political role. Asking questions about the ways in which texts either support or challenge dominant ideas about, for example, gender or race, may offer illuminating insights if you’re looking for a different approach, whether preparing for an exam or writing a coursework assignment. An imperialist world view One idea, which certainly dominated the late Victorian period and the early part of the 20th century, was that of Imperialism. With the Empire at the height of its power and influence, British citizens looked out at the world with a confident sense of superiority. The home country and the territories that it had colonised were associated with familiar values of order, reason and security, whereas beyond our shores, places and people existed associated with the very opposite – with, to use one of Said’s most influential and useful concepts, the ‘Other’. A first reading of Heart of Darkness might suggest that Conrad shares this Imperialist world view. London and Brussels seem to represent the former values whilst the Congo, constantly imagined as a location of ‘darkness’ seems to represent that which is strange, dangerous and irrational. Yet, as we analyse the text more closely, the different ways in which the narrative resists this simple binary opposition, and thus the ideological simplicity of Imperialism itself, become clear. Relishing binary oppositions From the novella’s opening the conventional contrast between a metropolitan well-organised society and an apparently threatening primitive African society – encouraged by the politicians and the media of the day – is undermined. Above the Thames, on which Marlow, the story’s narrator, waits to set out for his African voyage, the ‘air was dark’ and we are reminded that London, the centre of the Imperial mission to bring order to far-away lands, ‘has been one of the dark places on the earth’; ‘yesterday’ there was ‘savagery, utter savagery’. Conrad may make use of a familiar Orientalist idea – that the journey into the heart of Africa is a journey back in time to some primeval location – but he also wants us to recognise that the primitive is closer than we think; the ‘darkness’ is not only over there. The strangeness of the coloniser The subversion of conventional divisions, and thus of conventional ways of imagining the relationship between different cultures, is also implicit in Conrad’s decision to use the voice of Marlow to relate the tale – a character who, from the very beginning, seems set apart. With his ‘sunken cheeks ... a yellow complexion ... and ascetic aspect ... he resembled an idol’ – a figure of strangeness and mystery compared to his respectable bourgeois companions, who wait on the Thames for the ‘turn of the tide’. Charlie Marlow’s separation is a crucial element of Heart of Darkness, enabling Conrad to distance himself from the colonialism that he portrays. Whatever else Marlow is, he is not a simple representative or spokesperson for the unnamed Imperial Company which employs him. The absurdity and impersonal emptiness of this Company is suggested by the portrayal of its various employees. The Chief Accountant is more preoccupied with his appearance and the tidiness of his book-shelf than with the suffering around him. A manager’s ability to ‘keep the routine going’ perhaps indicates that ‘there was nothing within him’. And another agent is described as a paper-mâché figure, who has ‘nothing inside but a little loose dirt, maybe.’ Denied humanity, the colonisers are also rendered strange and insignificant by the often ironic imagery used to depict them – ‘pilgrims’ for a band of adventurers who seek ‘to tear treasure out of the bowels of the land’ and a ‘flock’ of small birds for a group of powerful officers. Through Marlow’s narration Conrad de-familiarises that which is meant to be most familiar to his readers: the characters and the institution of Empire. The ‘remarkable’ Kurtz Of course, Kurtz, the main object of Marlow’s imperial mission, is also, in his initial idealism – ‘All Europe contributed to the making of Kurtz’ – one of the main representatives of colonialism. Having ‘gone native’, most notably by forming a sexual relationship with an African woman, his white compatriots write him off. Even Marlow says that Kurtz ‘lacks restraint in the gratification of his various lusts ...’ However, unlike his fellow colonisers, he also affirms his ‘loyalty’ to this ‘remarkable man’ who had ‘something to say and whose ‘stare … was wide enough to penetrate all the hearts that beat in the darkness’; Kurtz, it seems, is a preferable ‘nightmare’ to that of his materialist self-seeking companions. His ability to slip out of one identity, constructed by race and profession, into another that is markedly more uncertain and unpredictable, appeals to Marlow and, arguably, Conrad. Straight-forward oppositions are also subverted by the ambivalence which surrounds Kurtz’s famous last words – ‘The horror! The horror!’ – which could refer either to his African experience or to his understanding of the true nature of colonialism, or indeed to both. Here, as well, Conrad’s text resists the easy ideological categories which we use to interpret and parcel-up the world. Representing the colonised If the colonisers are represented as inhuman and strange – as ‘Other’ – what about the way in which the colonised are portrayed in Heart of Darkness? Undoubtedly, some of the language used to describe the natives of the Congo is racist and offensive. Yet, Conrad’s representation of Africans is more complex and interesting than this judgement would suggest. Initially it is important to note that we do not see the natives directly but only through the sceptical and marginalised eyes of the narrator. We might expect then a certain degree of ambivalence in their depiction and we are not disappointed. This ambivalence emerges in those moments when Marlow recognises, across the differences he registers, as in a mirror, a common bond with the African people he encounters. His crew may be cannibals but unlike the stereotype, he comically observes that they do not ‘eat each other before my face’; rather they are ‘men one could work with, and I am grateful to them’. In spite of prolonged hunger they, unlike Kurtz, do exercise ‘restraint’. Similarly, the helmsman, who is ‘the most unstable kind of fool’ and ‘is of no more account than a grain of sand in a black Sahara’, is given significance by the description of him at his death, so much so that Marlow ‘has to make an effort to free my eyes from his gaze’; and a little later he talks of missing him and the ‘subtle bond’ that had formed between them. Another crew member might be a ‘savage’ but the narrator’s ironic perception that he sees the modern boiler of the colonisers’ boat as ‘witchcraft’, creates a subtle resemblance between African and European civilisations. Whilst Heart of Darkness by its insistence on the huge gulf between the continents of Europe and Africa, does endorse an Imperial view of the world, this gulf is also, as we have seen, repeatedly subverted. Conrad writes of the Africans – ‘They howled and leaped, and spun, and made horrid faces; but what thrilled you was just the thought of their humanity...’ The ‘Other‘ is both acknowledged here and rejected. What happens at the end? At the end of the novella also, expected and well-established divisions are folded. Visiting Kurtz’s fiancée on his return to Europe, Marlow sees her home as strange and violent as the African world from which he has returned. When she raises her arms and he sees a tragic and familiar Shade, resembling in this gesture another one, tragic also, and bedecked with powerless charms ... one image and culture is superimposed on another, so that single and separate identities – those of the white and black woman – are merged. Yet, Marlow cannot tell Kurtz’s fiancée the truth about his last words, for to do so would be to undermine another powerful opposition – that of gender. The European female has to be protected by a lie from ‘the horror’ which Kurtz discovered; his knowledge, just like Conrad’s, is just too disturbing and threatening for the maintenance of traditional roles and beliefs. The author may have serious quarrels with both patriarchy and Imperialism but he is not completely able to escape his own historical moment. If, however, traditional divisions and traditional attitudes are restored at the end of Heart of Darkness, this is only after they have been previously destabilised – a phenomenon common to many texts. Whilst the racist language of the book makes it difficult, even upsetting, to read, Conrad does succeed in challenging the Euro-centred view of the world that was dominant at the time of the book’s publication and that still shapes some current political thinking. Think, for example, of George W. Bush’s ‘axis of evil’ speech as another version of the ‘us-and-them’ ideological mind-set against which Heart of Darkness is written. As an alternative, Conrad’s novella promotes the value of mixing, blending and inter-mingling, the value of hybridity – a particularly appropriate value for an historical moment in which the first mixed-race man has become US President. Mike Peters is an AQA B A Level Literature coursework adviser and moderator, as well as a tutor for the Open University and WEA. This article first appeared in emagazine 44, March 2009.