case_study_e_the_ganges_river

Case Study E: The Ganges River

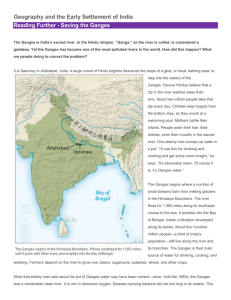

The Ganges River is part of the second largest river basin (the entire area drained by a river and its tributaries) in the world, after the Amazon. It begins in the Himalayas, passes though Nepal and India, forms part of the border between India and Bangladesh, and combines with other rivers in Bangladesh before emptying into the Bay of Bengal. More than half a billion people live in the Ganges River basin, forming the largest concentration of extremely poor people in the world.

While the Ganges regularly floods during the monsoon (system of heavy rainfall) season, both India and

Bangladesh experience water shortages during the dry months from January to April. Such shortages harm irrigation and agriculture in both India and Bangladesh, and water demand by both countries continues to increase. As is often the case when a major river flows through several countries, India and Bangladesh have been disputing the allocation of the river water since the 1950s.

India first made plans to divert water from the Ganges in the 1950s, primarily to ensure that there was enough water in the port of Calcutta, a megacity located on an offshoot of the Ganges River. Bangladesh

(part of Pakistan until 1971) opposed this proposal because it feared that an upstream diversion would have disastrous consequences on the southwest part of its territory. However, only seven percent of the

Ganges basin is in Bangladesh—most of the river basin lies in India. Bangladesh, though it has limited influence over Indian policy, thus suffers the consequences of any Indian diversion of the Ganges River.

In 1961 India decided to build a dam and a barrage, a dam placed in a watercourse to divert it into a channel for navigation or irrigation, at Farakka, just above the point where the water reaches the

Bangladesh border. Bangladesh protested this move but India stressed that construction of dams is a natural right of any country. In 1972 Bangladesh dropped its opposition to the project and the two countries agreed to share the flow of water during the dry season. The barrage became operation in 1975, but in 1976 Bangladesh felt that it didn’t receive its fair allocation of water. It brought the issue to the UN

General Assembly, which encouraged the two countries to conduct bilateral negotiations. The result was the Ganges Waters Agreement of 1977. This agreement, which was renewed in 1982 and 1985, specified

how the countries should share the low-season flow. The last agreement lapsed in 1988, and the countries were not able to agree to another treaty until 1996.

In the meantime, India’s diversion of water at Farakka has greatly affected Bangladesh. The decreased water supply below the barrage means that the Ganges no longer reaches its natural sea outlet during the dry season and saline water has advanced up the river delta. This has led to decreased agricultural productivity and fish stocks, the loss of forests, the contamination of groundwater and surface water.

Bangladesh estimates that the Farakka Barrage has affected a third of its population and caused the loss of 7.5 million tons of grain production and U.S. $3.5 billion between 1976 and 1995.

These factors made it more difficult for Bangladeshis in the region to make a living. Many moved to neighboring areas in

India in the 1970s and early 1980s in search of better employment and living conditions. Indians living in these regions, many of them in deep poverty themselves, felt threatened by the sudden deluge of immigrants. Several violent clashes between Bangladeshi immigrants and Indians broke out in the regions of highest Bangladeshi immigration, leading some Indian politicians to suggest deporting the

Bangladeshis.

Both sides finally signed a treaty in 1996 in which they agreed to share dry-season water equally for the next 30 years. The treaty mentions the need to increase dryseason flows in the long term, but does not specify how to do so. Both countries were satisfied with the sharing arrangements in the first two years of the treaty. If India and Bangladesh can agree on a way to increase the amount of water in the Ganges during the dry-season, they may be able to avoid future conflict and ecological damage in Bangladesh’s delta region.