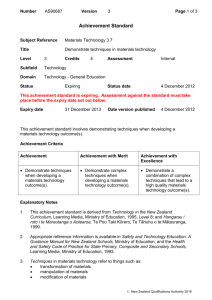

Independent Capability and Capacity Review

advertisement