Review of the Emergencies Act 2004

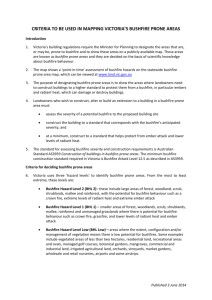

advertisement