(2011) Why consider skating and skate parks as a public health issue

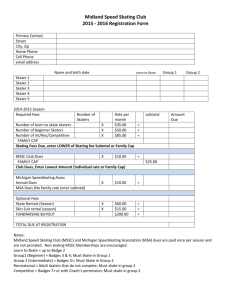

advertisement

Dr Lisa Wood Why consider skating and skateparks as a public health issue? WHY CONSIDER SKATING AND SKATE PARKS AS A PUBLIC HEALTH ISSUE? As defined by the World Health Organisation, health is not merely the absence of disease, but encompasses a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being1. Growing concerns about rising rates of physical inactivity and obesity among children and adolescents has drawn greater attention to the need to provide community facilities that encourage young people to be active. This includes not only facilities and public areas that cater to more traditional and formal sporting activity, but also those that provide for informal activity such as skateboarding, scootering and playground play. Mental health is also a growing public health issue among young people, and opportunities to socialise with peers and feel valued and catered for by local communities are emerging as protective factors for mental health that need to be considered in the way we plan urban environments 2. Youth physical activity as a priority health issue The rise in sedentariness and obesity in Australian children and young people is paralleled by a decline in children‘s physical activity levels 3. This can have lifelong repercussions, as higher levels of physical activity in childhood are associated with reduced risk of many chronic diseases later in life including heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, some cancers and obesity 4. Childhood obesity is increasingly described as a global epidemic 5, and it is projected that 25% of young Australians will be obese by 2025 if current trends are not reversed 6. While there are many contributing factors (physical education in schools, family influences) to childhood physical inactivity and obesity, environmental factors such as urban design and access to places in which young people can be active (including parks, playgrounds and skateparks) also influence how active young people are 2. National data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) indicates that youth participation in activities such as skating, rollerblading and scootering now outnumbers participation in more traditional sport, with up to 21% of Australian young people estimated to engage in skating 7. Similarly, a recent Western Australian study found that a higher proportion of children participated in non-formal physical activities than formal sport 8. A perceived risk of injury and liability has sometimes hindered support for skateboarding as a physically active and developmentally beneficial activity. However, research has shown that it results in relatively few serious injuries; approximately half the number associated with sports such as cycling or basketball. 9 Moreover, greater provision of skateparks could lessen the prevalence of skating related injury, as ―the more serious injuries resulting in hospitalisation typically involve a crash with a motor vehicle‖ 9, p697. Findings from a study by 1 Dr Lisa Wood Why consider skating and skateparks as a public health issue? Cohen 10 also suggest that skateparks may contribute to increased physical activity overall, with a six-fold increase in vigorous physical activity observed among males following the renovation of a local skatepark, highlighting the importance of providing community alternatives to combat the rise in sedentary youth pastimes 10. Social and mental wellbeing There is also a growing body of evidence linking physical activity to mental health benefits 11, adding weight to the importance of providing opportunities and facilities for a wide range of physical activities, including activities that engage young people who tend not to participate in more organized club or team based sports. While negative incidents associated with skateparks are more likely to receive media or local government attention, such parks actually have the potential to foster and reinforce many of the traits and skills that are recognised as protective factors for mental wellbeing. Skateboarding for example can prove young people with opportunities to develop self esteem and social competence 12. In research undertaken in Queensland, participants spoke of the opportunities skate parks provided for social interaction and social integration, along with the development of social skills, self-esteem, cooperation and respect for self and others 13. The opportunity to develop self esteem and social competence through skateboarding has also been noted in the international literature 13, p293. These are the types of valuable ‗life lessons‘ often enshrined in school curriculum, but which are learnt more powerfully in real life community contexts. Trends towards the exclusion of young people from public places in many western societies has received growing attention in the adolescent health and child development literature, and has the potential to adversely impact adversely on their mental health and sense of selfworth. As articulated in a report undertaken by the Youth Affairs Council of Victoria14, p7 ―the perception of young people in public places, especially those congregating in groups, is usually that they are up to no good.... as young people are often perceived as ‗troublemakers‘ their use of public space is increasingly regulated‖ Examples of an overt trend towards the exclusion of young people include policies and strategies to ‗move young people on‘ from shopping malls and other public places in which they may congregate14 and the prohibiting of activities such as rollerblading or skating in public areas15. Also of concern however are the more subtle ways in which young people may be made to feel unwelcome or uncatered for in parks and public places. This includes measures such as the ‗designing out of youth from public spaces‘ 16, removal of seating in areas in which young people may congregate or the fencing/locking of playgrounds and parks. Young people are well aware of the negative stereotypes that prevail and that are associated with their presence in public places. As noted by Woolley, ―perhaps the greater fear for teenagers is the fact they are often perceived by adults to be up to no good‖ 15. Young people are also frustrated by the diminishing number of places in which they can ‗hang out‘. 2 Dr Lisa Wood Why consider skating and skateparks as a public health issue? While the notion of young people ‗hanging out‘ is often associated with loitering or time wasting by adults, for young people themselves, it is an important and vital part of their social development17, particularly during the difficult adolescent years. Indeed, it has been argued that ―hanging out needs to be provided for in public places‖12, p161 as part of community efforts to support the healthy development of adolescents. Or as astutely observed by Jane Jacobs ―Adolescents are always being criticized for this kind of loitering, but they can hardly grow up without it‖18 . Problems associated with skateparks – what is the evidence? Unfortunately, skating and skateparks are sometimes the victim of broader societal concerns about young people or young people in public places 15, 16, 19; as articulated by Stratford ―concern among urban managers about skating in the city is part of a larger discourse on fear of crime, victimization, social control and urban design‖19. Prohibitions, ordinances and signage relating to skateboarding have become increasingly common in the public domain16, and while skate parks are often touted as the solution to problems associated with skating in public streets and areas, they too often encounter opposition. Where such skate facilities are placed also impacts on how skaters and young people are perceived and see that they are perceived in the community; as noted by Rogers and Coaffee this can sometimes represent an implicit form of ‗designing out‘ and passive dispersal: ―some urban authorities have begun to construct youth activity venues, such as purpose built skate parks, to accommodate youth demand to alleviate pressures on amenity spaces…. These venues are often located on the edge of city centres in luminal or marginal spaces. 16 1, p328 Owen similarly observes that skateboarding facilities are often located far away from other park activities or in less desirable locations 12. From our review of the evidence, there is very little published research or data to substantiate the types of negative stereotypes about skating and skateparks that often arise. More broadly but relatedly, there is increasing scrutiny and concern within public health about the way in which media publicity can distort public perceptions relating to community safety and social issues. As noted in a recent review of evidence undertaken for VicHealth, the media has been culpable in the escalation of largely unfounded parental fears about childhood safety and abduction20. Images of adolescents in the media prompt and reinforce a public perception that ―conjures up images of delinquency, violence, or nonconformity‖ 21. Young people generally are more likely to be portrayed negatively rather than positively in the popular media and skaters and skateparks are no exception22, p214. Headlines such as appeared in the Courier Mail in Queensland (Skate parks a haven for drugs, violence and gangs in southeast Queensland, 2010) are emotively worded and serve to fuel public debate and misperceptions about young people 23. Skaters ‗doing the right thing‘ and skateparks without problems do not however make the news. 3 Dr Lisa Wood Why consider skating and skateparks as a public health issue? It is also important to distinguish between community concerns that may relate to skateparks versus skating in general. As noted by Aperio Consulting, because of a lack of publicly provided skateparks, skaters do sometimes use public and private parking lots, business plazas, streets, and sidewalks for their sport—none of which are intended or designed for skateboarding 24. This can serve to fuel tensions relating skating that could be averted by the provision of more designated skate areas and facilities. Concerns about undesirable social behaviour are often cited by those opposing skateparks or provision for skaters in cities and suburbs. However actual evidence supporting these assertions is scant. In fact, evidence actually indicates that ‗the lack of things for young people to do‘ is a greater risk for undesirable behaviour. In a study of over 1100 adolescents (12-18 years), those who believed there was not enough to do in their neighbourhood were 1.7 times more likely to offend than are adolescents who are satisfied with their neighbourhood 25. Conversely, providing options for young people‘s leisure can help to prevent of risky behaviour, including crime and delinquency 26. A US study reported that neighbours living within 5 blocks of a park with skate facilities had not witnessed serious crimes in that area, and concluded that the inclusion of a skate area within the park actually reduced problems by bringing in more users and more ―eyes on the park‖ 24, p11. Designing to minimise problems There is growing evidence and impetus in urban planning generally in the notion of ‗designing out crime and anti-social behaviour‘ 27. Unfortunately, when it comes to facilities and amenities for young people (such as skate parks, basketball half courts), this is sometimes translated into ‗not providing the facility at all‘, rather than the application of sound design principles to minimise undesired activity. From our review of the literature, many perceived or potential problems can be mitigated through good planning and design. Good skate-park design includes 28-31: Integration with other recreational activities Open plan with no fences Central location with easy access to public transport and facilities Good visibility (eyes on the street, be it from other park users or passing pedestrians or traffic) Lighting Maintenance Appropriate structures and surfaces for various levels of experience The issue of maintenance and care for facilities such as skate parks, is interesting, for as noted by Bradley, they are sometimes ―built and then ‗left to look after themselves‘. If neglected in this way, antisocial individuals are attracted, antisocial behaviour flourishes, and negative stereotypes regarding the adverse developmental impact of skate parks thus appear confirmed.‖ 13 Pg303 The reality is that all public places and community assets can fall 4 Dr Lisa Wood Why consider skating and skateparks as a public health issue? victim to incivilities (e.g. broken glass, graffiti, litter) and require regular monitoring for problems and maintenance. As articulated recently by a landscape designer and planner with Parks Victoria, ―if a park or playground is well used by the community, we should just factor in the costs of vandalism and maintenance in the same way that we accept and expect to spend money on pruning roses and mowing lawns in other park areas.‖ 32 There are other measures that can also positively influence young people to ‗own‘ and care for skate park areas. In my own observational study of skate park signage for example, some focuses on appealing to skaters as ‗responsible citizens‘ while other signs take a more authoritarian or draconian rules based approach in the wording. While I am not aware of any research that has specifically investigated the relative effects of different signs in relation to skating, the issue is not dissimilar to one that often arises in relation to encouraging responsible dog ownership in parks, with research indicating signs that affirm dog owners to do the right thing by others and the park are more effective in increasing compliance than those that are more negatively worded 33. Similarly, informal norms and ‗peer influence‘ to do the right thing has emerged as a powerful influence on dog owners 34 and the same type of informal norms can also be harnessed among skaters. As noted by Bradley although skate parks may lack adult-imposed mechanisms for behavioural control, these activities and leisure contexts provide forms of control that are internal either to individual participants and/or their group. 13 p293 Consulting with young people The needs and views of adolescents and young people are often overlooked in urban planning and design 12, 17, or as expressed by Mathews et al, ―at best environments are built for children, not with children‖ 35. A Victorian inquiry into sustainable urban design noted that it is rare for young people to be consulted about the design of public open space 36 . Community consultation is also increasingly touted and used in community planning, but is primarily undertaken with adults or key stakeholder groups. Obtaining input from children and young people has additional complexities, and seems to be often rendered ‗too hard‘ or it is seen as suffice for adults to speak on their behalf. But not consulting the users can backfire. As identified in a paper published in the Journal of Youth studies, some skate parks built for the purposes of solving the ‗youth problem‘ and regulating teenagers‘ use of space, which did not engage with young people themselves therefore failed to tap into the knowledge, expertise, values, trust and networks that made teenagers‘ own self-directed projects successful. 37, p567 By contrast, involving young people can foster a sense of ownership of public places in a way that merely providing them with facilities cannot do 38. The engagement of local skaters in a recent park redevelopment project at Fleming Reserve in High Wycombe illustrates this well, as reflected in the following account from the Fleming Reserve Project Coordinator (Shire of Kalamunda). Initial funding to develop a concept plan was sourced through the WA Office of Crime and Safety in 2008 in response to residents‘ concerns that the declining condition of park infrastructure and increasing levels of vandalism and disruptive behaviour were stopping many residents – particularly children and families – from using the park. 5 Dr Lisa Wood Why consider skating and skateparks as a public health issue? There has been ongoing involvement of current users in discussions about skate park design features opened up opportunities to engage local young people in conversations about graffiti and tagging, littering and damage to the local bush reserve – and how these issues were negatively perceived by some older residents. While these conversations have not stopped all further damage from occurring, the level of graffiti and litter within the park has markedly decreased over the past twelve months. Skate park users are keen to see the project proceed and now the design has been approved and building is due to commence before the end of this year, local young people are offering solutions and ideas about how the skate and BMX area can best be kept clean and well-maintained, and what events they can help organise within the park. Engaging young people in the planning and design of facilities such as skateparks can also foster civic engagement and a sense of ‗ownership‘ of local facilities. In a study on the Isle of Wight for example, participants were afforded opportunities to liaise with and recruit members of their community, family and the wider society through the construction and maintenance of the skatepark, and could ―take great responsibility over their skateparks, although they are afforded few rights outside that arena‖37, p566. ―Young people need a free and democratic space where they can relax and socialise without close parental supervision. Many entertainment venues are off limits to under 18s, or are priced beyond reach. Reliance on public transport also means using public space‖ 39, p1 In conclusion Skateboarding is a popular recreational activity for young people in Australia. It provides important opportunities not only for physical activity, but also for social interaction with peers, and for the development of the types of important life skills that come about informally as they learn to cooperatively take turns, interact with others, work on new skills, and face new challenges. Yet children and adolescents are often overlooked or ‗designed out‘ of public places, or discouraged from activities (such as skating or ‗hanging out‘), and this conveys mixed messages to young people about the way in which they are viewed, valued and catered for in the community. Concerns about undesirable social behaviour often underlie opposition to skateparks or provision for skaters in cities and suburbs. However actual evidence supporting these assertions is scant, and in fact, ‗the lack of things for young people to do‘ is a greater risk for undesirable behaviour. Good placement and planning of skateparks can minimise many of the perceived problems. 6 Dr Lisa Wood Why consider skating and skateparks as a public health issue? Young people need things to do and places where they are free to be themselves within our cities and suburbs – this needs to includes not only facilities and public areas that cater to more traditional and formal sport, but also those that provide for skateboarding as a popular and healthy form of recreational and social activity. REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. WHO. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization; 1948 ARACY. Parks and Open Spaces: for the health and wellbeing of children and young people: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth; 2009. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Health of Children in Australia: A Snapshot, 2004-05. 2007 [cited 2010 24 August]; Avail from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mf/4829.0.55.001/. CDC. Physical activity and good nutrition: Essential elements to prevent chronic disease and obesity. At a glance 2007. Atlanta: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007 Kumanyika S, Jeffery R, Morabia A, Ritenbaugh C, Antipatis V. Obesity prevention: the case for action. International Journal of Obesity. 2002;26:425-36. Australian Society for the Study of Obesity, Obesity in Australian children. Australian Society for the Study of Obesity; 2004. ABS. Children’s Participation in Organised Sport and Leisure Activities; 2009. Martin K, Rosenberg M, Miller M, al. e. Trends in Physical activity, nutrition and body size in Western Australian children and adolescents: The Child and Adolescent Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (CAPANS) 2008. Perth: Physical Activity Taskforce; 2010. Kyle S, Nance M, Rutherford Jr G, Winston F. Skateboard-associated injuries: participationbased estimates and injury characteristics. The Journal of Trauma. 2002;53(4):686. Cohen D, Sehgal A, Williamson S, Marsh T, Golinelli D, McKenzie T. New recreational facilities for the young and the old in Los Angeles: policy and programming implications. Journal of public health policy. 2009:S248-S63. Boutcher SH. Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being Taylor & Francis; 2007. Owens P. No teens allowed: The exclusion of adolescents from public spaces. Landscape Journal. 2002;21(1):156. Bradley G. Skate Parks as a Context for Adolescent Development. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2010;25(2):288. Youth Affairs Council of Victoria. Space Invaders? Young People and Public Space. Forum Report, June 2005; 2005. Woolley H. Excluded from streets and spaces? Sheffield Online Papers in Social Research. 2003;7. Rogers P, Coaffee J. Moral panics and urban renaissance. City. 2005;9(3):321-40. Passon C, Levi D, del Rio V. Implications of adolescents' perceptions and values for planning and design. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 2008;28(1):73-85. Jacobs J. The death and life of the great American cities. New York: Random House; 1961. Stratford E. On the edge: a tale of skaters and urban governance. Social & Cultural Geography. 2002;3(2):193-206. Zubrick SR, Wood L, Villanueva K, Wood G, Giles-Corti B, Christian H. Nothing but fear itself: parental fear as determinant impacting on child physical activity and independent mobility. Melbourne, Victoria; 2010. 7 Dr Lisa Wood 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. Why consider skating and skateparks as a public health issue? Owens PE. No Teens Allowed: The Exclusion of Adolescents from Public Spaces. Landscape Jrnl. 2002 January 1, 2002;21(1):156-63. Camino L, Zeldin S. From periphery to center: Pathways for youth civic engagement in the day-to-day life of communities. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6(4):213-20. Weston P ,. Skate parks a haven for drugs, violence and gangs in southeast Queensland The Sunday Mail. 23 May 2010. Aperio Consulting. The Urban Grind: skateparks: neighborhood perceptions and planning realities. 2005. Lynch M, Ogilvie E. Access to amenities: the issue of ownership. Youth Studies Australia. 1999;18(4). Caldwell L, Smith E. Leisure as a context for youth development and delinquency prevention. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2006;39(3):398-418. Taylor R. Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED): Yes, No, Maybe, Unknowable, and All of the Above. Handbook of Environmental Pschology. 2002. City of Norwood,. Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED): guidelines for local government. Norwood; 2006. Thompson F. Skateboard Jungle. The Newcastle Herald. 2010. Woolley H, Johns R. Skateboarding: the city as a playground. Journal of Urban Design. 2001;6(2):211-30. Buskens N, Harbottle, R. Skate Park Operations Manual. Melbourne: YMCA Victoria; 2005. Healthy Parks Healthy People Conference Participant. Personal communication. April 2010. Hughes M, Ham S, Brown T. Influencing Park Visitor Behavior: A Belief-based Approach. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration. 2009;27(4):38-53. Cutt HE, Giles-Corti B, Wood LJ, Knuiman MW, Burke V. Barriers and motivators for owners walking their dog: results from qualitative research. Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 2008 Aug;19(2):118-24. Matthews H, Limb M, Percy-Smith B. Changing Worlds: the Microgeographies of Young Teenagers. 1998;89(2):193-202. Victorian Parliament. Inquiry into Sustainable Urban Design for New Communities in Outer Suburban Areas. Melbourne: Victorian Government, Outer Suburban/Interface Services and Development Committee; 2004. Weller S. Skateboarding alone? Making social capital discourse relevant to teenagers’ lives. Journal of Youth studies. 2006;9(5):557-74. City of Darebin. City of Darebin: Young People in Darebin Parks, Research Project. Victoria: Success Works; 2005. Youth Justice Coalition and Youth Action and Policy Association. Young People and Public Space: workshop presentation at Scales of Justice Conference. 2002. Suggested citation: Wood, Lisa (2011) Why consider skating and skate parks as a public health issue; a review of evidence. Centre for the Built Environment and Health, School of Population Health, The University of Western Australia. lisa.wood@uwa.edu.au 8