SIA_Report_FINALPRINT - UQ eSpace

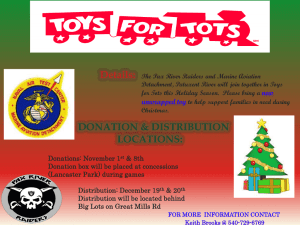

advertisement