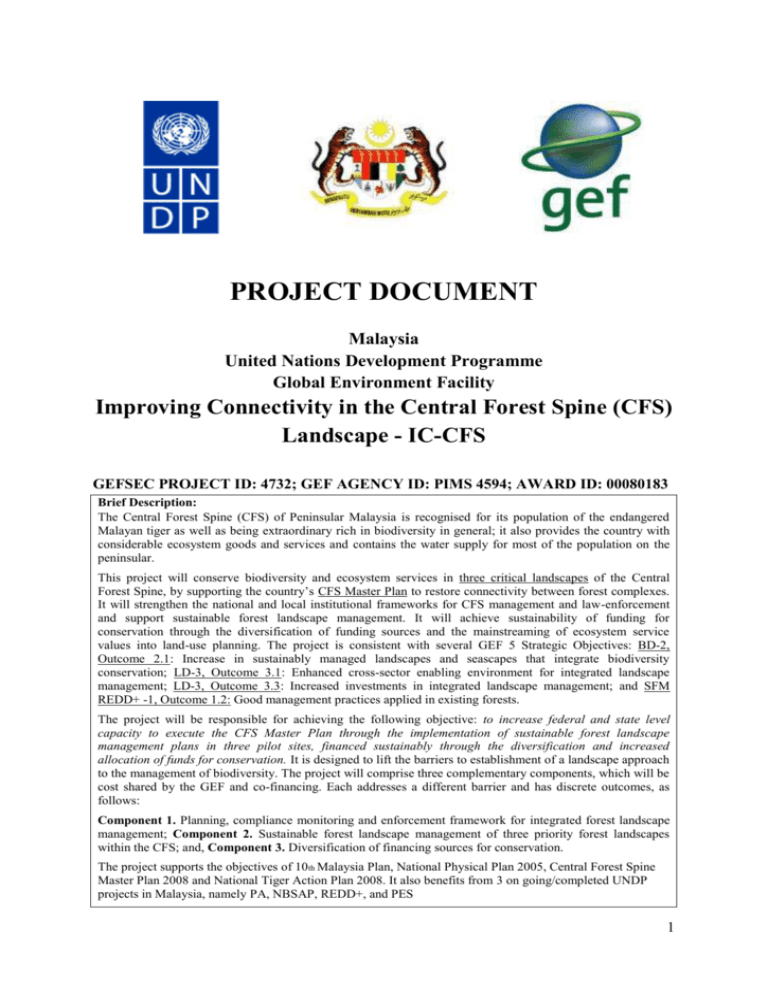

4594 Malaysia IC-CFS Project Document 07-01-2014 (Final

advertisement