Study Guide: Diverse Learners

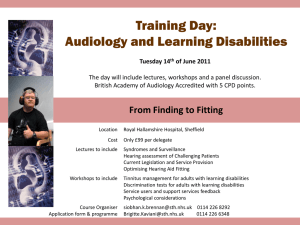

advertisement