Abstract 4 5th vienna music business research days

advertisement

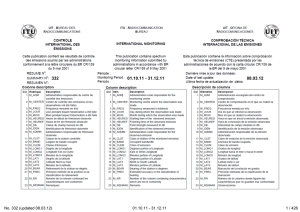

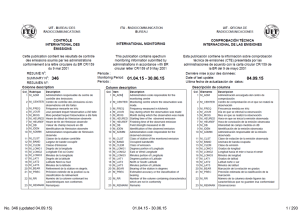

Music Identification Software as a tool for precise monitoring of real music use in public spaces and fair distribution of music rights income SERGEJ LUGOVIĆ Polytechnic of Zagreb, University of Applied Sciences Vrbik 8, 10 000 Zagreb CROATIA slugovic@tvz.hr NIVES MIKELIĆ PRERADOVIĆ Department of Information and Communication Sciences Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb I. Lucica 3, 10000 Zagreb CROATIA nmikelic@ffzg.hr http://www.ffzg.unizg.hr/ Keywords: music collective rights management, viable system model, music identification software, music information retrieval, transaction cost theory, information behaviour Objectives of the research We can observe two important trends in the today's music industry. One trend is development of information technology which processes information according the music industry demands, such as music recommendation algorithms (1), music identification software (2) and web services (3) to serve emerging needs of the music industry in the information age. The second one is diversification of incomes streams (4,5,6) including streaming services, copyrights income and live performance. The main objective of this research is to find relations between those two trends and how they influence each other from the perspective of systems thinking. Precisely speaking, the main question is: Can a music identification software be used to improve transparency of music copyrights income distribution? Brief description of the disciplinary/theoretical context/background This research follows the information through the whole music system, from the public space where music is consumed to the distribution of income collected (7) by Collective Rights Management Organisations (CRMO). To do so, we have to use different scientific disciplines, such as information science, economic science, systems science and computer science. Putting it into a theoretical context we will use music information retrieval, transaction cost and system theories. Basic assumption of the research is that music industry in the 21st century should be viewed as a system (8) which connects music creators and music consumers in a economical way, satisfying cognitive needs of a particular user of the system, along with socio-cognitive needs of different stakeholder groups. Such system should be based on premises of using existing technologies in a way to optimize functions, processes and structures for all participant sin order to satisfy their needs. Research questions and/or hypotheses The primary hypothesis of the research is that music identification software (MIS) could be used to recognise music in public spaces. The second hypothesis is that collected information could be used in the music system and bring benefit for most of the stakeholders. Following hypothesis questions will be answered: Which MIS could be used? How are they working? How precise are they? What are the procedures of their successful implementation? There are also two technical questions: How do information flow through the system? and What are the effects of such new patterns of information flow? As CRMO are just a part of the music system, we have to address the question how such new information behaviour patterns are aligned with higher order system strategies. Methodology and results overview In this research the authors follow the research and experiment published in (9) where accuracy of Shazam application in music identification was analysed. A playlist was captured and analysed in a nightclub environment on two different mobile phones. Later, the same playlist was analysed by comparing results in a home studio environment. The findings from this research show that Shazam is not precise enough to be used as technology for monitoring music in public spaces. While conducting the research the authors discovered another technology which could identificate music at a much higher rate. The dataset from the published research will be used to evaluate another technology and compare it with previously published results. From the preliminary interview with the management team of the company in possession of mentioned technology we can see that the technology is beeing used on different festivals across Europe. Some CRMO are already recognising importance of having transparent data for the purpose of better serving their members. After comparing the datasets and results, a case study will be presented, primary covering the relationship with artists, users of public space, music events organisators and CRMO. After collecting and analysing data we have evidence that music system, in primary CRMO system, has the opportunity to capture data about music consumption, at a lower cost. This kind of an impact on how information behave (10) in the CRMO system and how they influence the economic of such system (11). An applied system modeling technique was applied in the research to construct generic model of information behaviour in such system, addressing different stakeholders (figure 1). Figure 1 Generic model of music information flow in CRMO stakeholders ecosystem The presented model is generated on the fundamentals of the transaction cost theory proposed by Ronald Coase (12). To evidence such model, literature review was done, addressing economic (13), management (14) and computer science perspectives (15). While researching the literature about economics of CRMO research found lack of availability of research data and at the same time evidence of importance of precise and transparent measurement of music consumption. As CRMO are the part of the higher order music system, the Stafford Beer Viable System Model (16) was used to define different sub systems and their interdependencies in the context of the EU. For the purpose of this research we have tried to define a system on basis of information flow from the music use in public spaces to the payment to artists who actually write music. As System 1 we propose public spaces where music is consumed, artists whose music is used and their reporting on the use of their music and music event promoters. All of them participate in the reducing complexity of the environment, by participating in reporting of the actual music use in public spaces. As System 2 we propose the role of CRMO that actually process information collected from the environment and their role in the system is to distribute income based on collected information about music consumption. System 2 is supposed to coordinate activities, but it often used for a topdown control approach (17). System 3 is in our opinion the missing link, as there is no strong evidence of organisations which are evaluating the process how the information is collected, what kind of technology is used, what are the cost of the system two and so on. Another role of the System 3 is that it should report to System 4 and 5. In case of CRMO they are collecting the information and distributing the money, and at the same time they are communicating with higher order systems such as governments, without having established control procedures between them. Evidence from Croatia's 1 governance model will be presented in this research. Reviewing the literature we have found that there was an initiative in Brazil to install System 3 (18). System 4 would be government agencies which are accrediting the CRMO to operate by law. Such government agencies should communicate with an environment through continuous feedback and at the same time build identity of the overall system. That is why such agencies, as we can see System 4 has the responsibility to improve the perception of importance of economics and social impact of system of music rights, not just giving the licence to CRMO to operate. System 5 is EU, its particular agencies and initiatives that define policies which influence a wider set of interests, like social interests of transparent society and fair distribution of earned income. Main or expected conclusions / contribution We hope that this research will contribute to the multidisciplinary research of music income distribution along the whole system, from creator to user. Evaluation of available technologies for purpose of information processing through the whole system and generic model proposal are contributing to domain as a basis for further discussion. In addition the system analysis using VSM indicate the need for evaluation of current state of the CRMO ecosystem. Such broad approach proposed in this research addresses the issues of the new context of CRMO environment influenced by ICT. As the old proverb says we 1 Evidence of Croatian CRMO governance will be presented in a paper. Croatian government agency is directly enabling and controlling CRMO, which indicates missing link of System 3. cannot see the forest for the trees, which leads us toward a dramatic effect of erosion of the trust in the legal system (19). Main references 1. Celma, O. (2010). Music recommendation and discovery: The long tail, long fail, and long play in the digital music space. Springer. 2. Haitsma, J., & Kalker, T. (2003). A highly robust audio fingerprinting system with an efficient search strategy. Journal of New Music Research, 32(2), 211-221. 3. Knowles, J. D. (2007). A survey of Web 2.0 music trends and some implications for tertiary music communities. 4. Frost, R. L. (2007). Rearchitecting the music business: Mitigating music piracy by cutting out the record companies. First Monday, 12(8). 5. Myers, G., & Howard, G. (2009). Future of Music: Reconfiguring Public Performance Rights, The. J. Intell. Prop. L., 17, 207. 6. Thomson, K. (2013). Roles, revenue, and responsibilities: The changing nature of being a working musician. Work and Occupations, 40(4), 514-525. 7. Kretschmer, M. (2005). Artists' earnings and copyright: A review of British and German music industry data in the context of digital technologies (originally published in January 2005). First Monday. 8. Lugović, S., & Špiranec, S. (2013). Mutation of Capital in the Information Age: Insights from the Music Industry. The Future of Information Sciences. 9. Lugović, S., & Preradović, N. M. (2014). Challenges of Music Recommendation Software, WSEAS conference 10. Wilson, T. D. (1997). Information behaviour: an interdisciplinary perspective.Information processing & management, 33(4), 551-572. 11. Shapiro, C., & Varian, H. (1998). Information rules. Harvard Business Press. 12. Coase, Ronald (1937). The Nature of the Firm. Economica (Blackwell Publishing) 4(16). pp. 386–405. 13. Connolly, M., Krueger, A.B. (2007) Rockonomics: The Economics of Popular Music. The Milken Institute Review 9(3). pp. 50–66. 14. Hracs, B. J. (2012). Management Matters. Martin Prosperity Institute, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto. 15. Müller, M. (2007) Information Retrieval for Music and Motion. Berlin: SpringerVerlag. ISBN 9783540740476. 16. Beer, S. (1981). Brain of the firm: the managerial cybernetics of organization. New York: J. Wiley. 17. Espejo, R. (1990). The viable system model. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 3(3), 219-221. 18. Grassmuck, V. (2011). A Copyright exception for monetizing file sharing: a proposal for balancing user freedom and author remuneration in the Brazillian copyright law reform. RETHINKING MUSIC, A Briefing Book, Berkman Center for Internet and Society, Harvard University 41 19. Lawrence Lessig, Address at re:publica 09 (Mar. 2, 2009), quoted at: Volker Grassmuck, The World Is Going Flat(-Rate), IP Watch (May 11, 2009), http://www.ipwatch.org/weblog/2009/05/11/the-world-is-going-flat-rate/.