Two Dawns: How Richard Wagner and Then

advertisement

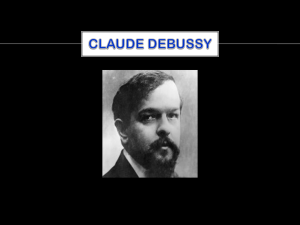

Two Dawns: How Richard Wagner and Then Claude Debussy Both Started the Same New Era of Music By Alissandra Reed Many analysts have considered both Richard Wagner’s Prelude to Tristan und Isolde and Claude Debussy’s Prelude to “The Afternoon of a Faun” to be turning points in the development of modern music. Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, completed in 1859, is credited by some as marking the starting point of modern music, while Debussy’s Prelude, composed roughly 35 years later, receives the same credit from other scholars. Debussy, having been interested in and influenced by Wagner’s work after experiencing one of his operas in 1889 (only three years before he composed the Prelude), later referred to Wagner as “a beautiful sunset that was mistaken for a dawn” – claiming that the German composer’s work was not as revolutionary as it was made out to be, and presumably implying that his own work was going to be the true dawn of new music. In analyzing and comparing these two preludes, many similarities can be found in the composers’ use of chromatic melody and harmony, form based on recurring symbolic motifs, and key area relations of thirds. Though there are also many differences which display two different compositional methods, these similarities evidence Wagner’s influence on Debussy, and likewise modern music as a whole. Both preludes’ opening themes are almost entirely based on chromatic stepwise motion. Debussy opens his prelude with a monophonic chromatic descent and then immediate ascent in the distance of a tritone, while Wagner writes the top two voices of his opening motive (known as the “desire” motive) each moving a minor third chromatically in contrary motion. Wagner’s use of chromaticism here leads toward a quasi-functional chord (V7/A, though it never resolves), but Debussy’s includes no harmonic function. In fact, the same melody recurs a few times throughout the piece, if slightly altered, with varying harmonies. Throughout both preludes, many of the harmonies are created not out of traditional tonic-predominant-dominant functional framework, but of chromatic movement. It is evident that chromaticism reigns over functionality from both pieces’ scarcity of V-I cadences. This lack of cadences to separate phrases and resolve dominant chords was one of the elements that made the preludes to Tristan und Isolde and “The Afternoon of a Faun” stand out as innovative compositions. Neither of these preludes follows closely any traditional musical form, but they are both organized with recurring melodic motifs. Wagner is known for his frequent use of “leitmotifs”—that is, short, recurring musical motifs which represent a person, place, or idea. Throughout the Tristan prelude, there are six main motifs that appear a number of times, in different keys and contexts. These leitmotifs attain their meanings within the opera, though it becomes clear during the Prelude that they each have meaning, due to their repetition in creating the form. Similarly, but to a lesser extent, the Prelude to “The Afternoon of a Faun” is somewhat formally based on recurring motifs. Its opening flute line, which represents the faun’s reed pipes, reappears many times throughout the work, sometimes literally and sometimes having undergone transformations. This piece does broadly fit into the traditional ABA’ form, but with some ambiguity as to where B and A’ exactly begin. There seem to be transitional phrases between sections (i.e. mm. 31-54 and mm 79-93) made up of melodies which are based on the opening flute motif. While this prelude is not built of as many recurring motifs as Wagner’s, its main idea reoccurs, transformed and intact, to build up the sections and form of the piece. This focus on small non-harmonically based ideas as formal building blocks was another characteristic of these composers’ works that represented a shift in musical tradition. Another interesting characteristic these two works share is their tendency to modulate to keys minor or major thirds away from each other. The opening theme of Tristan und Isolde iterates three times at the onset of the piece, first in A, then C, and finally E. Throughout the piece, the Tristan chord in its original pitch classes can and does function as a predominant in three keys, each a minor third apart: A minor in the opening statement, C minor at the end of the prelude, and Eb major during the climax where it functions as a French augmented sixth predominant. Similarly, Debussy’s prelude finds structural importance in third relations between keys. The piece, broadly fitting the ABA’ form, opens A and A’ and closes A’ in E major while the B section is in Db major (enharmonically imagined as C# major), a minor third below the first key. Though both the Tristan prelude and that of “The Afternoon of a Faun” visit many keys from start to finish, it is notable that both of their most prominent keys are based on third relations. The idea of third relations among key areas was certainly not one that either of these composers created – it had become rather common earlier in the Romantic era – so this commonality is not one that relates to the pieces’ novelty and importance in introducing modern music, but demonstrates the similarity in just how far from the norm they really were. Based on all of these similarities, it seems that Debussy’s perceived start of modern music was not so different from Wagner’s. Debussy does have some notable differences in his prelude, such as his focus on timbre or color as a main communicative element of his music, but many of the elements that are supposed to have been new and contribute to his prelude’s perceived place at the beginning of modern music are the same elements that put Wagner’s prelude there 35 years earlier. It seems that if, as Debussy alleged, Wagner was just a sunset, then so might he himself have been. Still, the 20th century yielded many new types of music, so why should it be limited to one starting point? Perhaps both the Prelude to Tristan und Isolde and the Prelude to “The Afternoon of a Faun” were dawns on a new and exciting era of composition.