Tail of a whale

advertisement

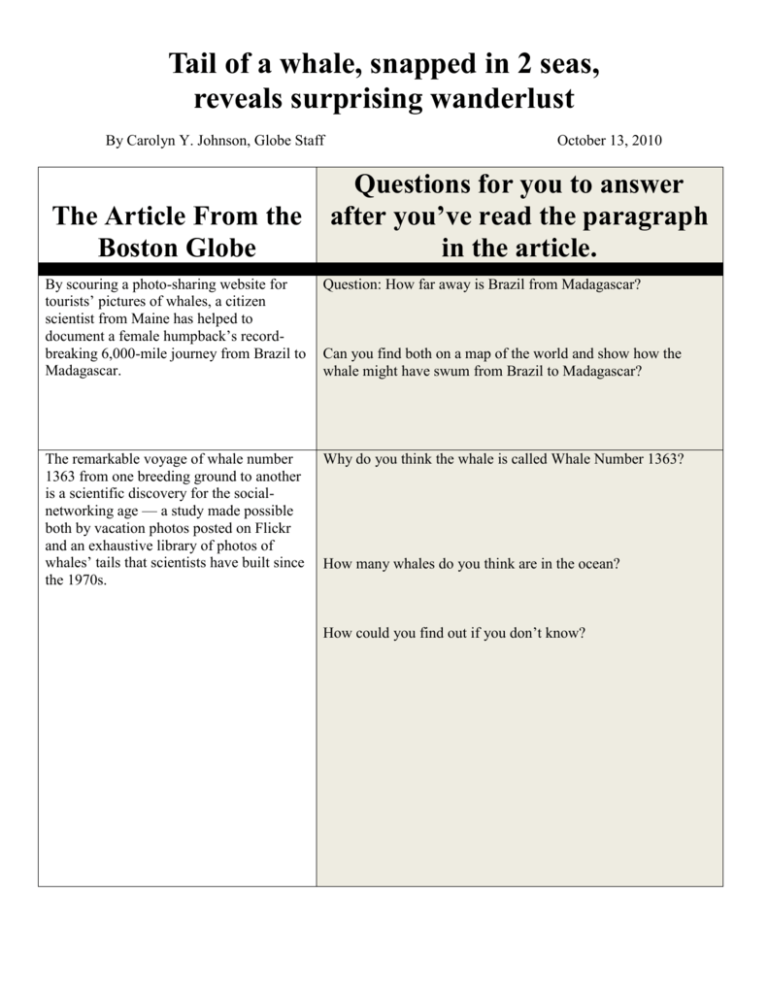

Tail of a whale, snapped in 2 seas, reveals surprising wanderlust By Carolyn Y. Johnson, Globe Staff The Article From the Boston Globe October 13, 2010 Questions for you to answer after you’ve read the paragraph in the article. By scouring a photo-sharing website for tourists’ pictures of whales, a citizen scientist from Maine has helped to document a female humpback’s recordbreaking 6,000-mile journey from Brazil to Madagascar. Question: How far away is Brazil from Madagascar? The remarkable voyage of whale number 1363 from one breeding ground to another is a scientific discovery for the socialnetworking age — a study made possible both by vacation photos posted on Flickr and an exhaustive library of photos of whales’ tails that scientists have built since the 1970s. Why do you think the whale is called Whale Number 1363? Can you find both on a map of the world and show how the whale might have swum from Brazil to Madagascar? How many whales do you think are in the ocean? How could you find out if you don’t know? “This to me is just an incredibly exciting way of reminding people they are our whales — they’re not the biologist’s whales,’’ said Gale McCullough of Hancock, Maine, who has become a liaison to Flickr for the Allied Whale research group at the College of the Atlantic in Bar Harbor, Maine. She regularly scours the popular website for humpback whale photos and uses expertise she’s honed over more than three decades of identifying whales by the shape and color of their tails, as well as the patterns on the undersides. Each whale’s tail, or flukes, is distinct. Each whale’s tail is distinct. Whale 1363 in the Antarctic Humpback Whale Catalogue made its first appearance in the annals of science in a most conventional manner. It was first spotted by scientists off the coast of Brazil in August 1999, swimming with another whale for an hour. The scientists took skin samples and did genetic analyses, determining that both whales were female. Was the whale a male or female? What does “distinct” mean? What parts of your body are distinct from the same part on other people’s bodies? Are you a male or a female? What do those words mean? A male is a: A female is a: Then, two years later, Freddy Johansen, a Norwegian tourist on a whale watch cruise, took an auspicious photo of the same whale’s flukes as it swam with two other whales off the east coast of Madagascar. Did you see the movie Madagascar? If so, what was your favorite part? What does the word “auspicious” mean? “It was only a short trip taken on a whim in between scuba diving and exploring of this small island off Madagascar’s east coast,’’ Johansen, chief executive of a workshop that specializes in exhaust systems for cars, wrote in an e-mail. What does an exhaust system on a car do? If you don’t know, how will you find out? In 2009, Johansen uploaded the photos What does it mean to “upload” something? from his trip to Madgascar to the website to back up his images and share them with friends. McCullough found them on a search. Could you upload your parents? She saw in the speckled pattern on the underside of the whale’s white tail a configuration that reminded her of a face, and the same pattern leaped out again when she looked in the Antarctic Humpback Whale Catalogue. She brought the match to scientists at the College of the Atlantic, where she works as a research associate. What does “speckled” mean? Who is the “she” in this paragraph? Do you think it was normal or remarkable that she noticed that the whale tail might be from the same whale? Do you think the pictures all show the same tail? How do you know? Photo Caption: The distinctive tail of Whale 1363 was photographed off the Brazil coast in 1999, and off Madagascar two years later. (Courtesy Allied Whale, College of The Atlantic) What does “caption” mean? Why do you think the Boston Globe put the phrase “Courtesy Allied Whale, College of the Atlantic” underneath the picture? Who do you think owns the photographs? Typically, humpback whales swim long distances to travel from feeding to breeding grounds — around 3,000 miles, according to Peter Stevick, a biologist at College of the Atlantic and the lead author of the paper published yesterday in the journal Biology Letters. What do you think “a journal” is? If you don’t know, how could you find out? “This record is unusual, not only in being longer than any of those recorded migrations, but because it’s not between a feeding ground and a breeding ground — it’s between two different breeding grounds,’’ Stevick said. He said it is not known why the whale would have made the trip. One possibility is the whale swam too far following prey and then swam back to Madagascar to breed. Is the trip from Brazil to Madagascar normal for Humpback whales, or is it longer or shorter than normal? Although it is believed to be rare for whales to swim such a long way, it suggests scientists should look harder at whether this movement occurs, to a less extreme degree, in other whales, Stevick said. It is also intriguing, he said, because male whales are the ones thought to roam widely. Do male or female Humpback whales tend to swim longer distances? What in the paragraph on the left tells you the answer to this question? What in the paragraph at the left tells you the answer? Phillip J. Clapham, leader of the Cetacean What is a “leader”? Ecology and Assessment Program at the National Marine Mammal Laboratory in Seattle, who was not involved in the research, wrote in an e-mail that it was very unusual for a whale to travel so far. Do you know any leaders? If so, what do they do? “This remarkable movement shows either that humpback whales are amazingly flexible, or that they’re capable of making amazingly large navigational mistakes!’’ Clapham wrote. What does “navigation” mean? What does it mean to make a navigational mistake? Have your parents ever made a navigational mistake? What did they do? Richard Merrick, chief of the resource evaluation and assessment division at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center, said that increasingly, citizen scientists are making important contributions, whether they are fishermen, tourists, or whalewatchers. Because they may look in places that aren’t being studied, he said, they may make important finds. Could you be a “citizen scientist?” Yes or no. If so, how would you do that? What kind of scientific exploration would you like to do? For Johansen, whose first passion is nature and wildlife, the chance to take part in a scientific discovery has been a pleasure. Was Johansen a “citizen scientist?” Yes or no. “This is my first time as coauthor of anything at all,’’ Johansen wrote. “You can imagine my surprise when it turned out the way it did!’’ Did she like it? Yes or no. How do you know? Carolyn Y. Johnson can be reached at cjohnson@globe.com. Who is Carolyn Y. Johnson? Would you like to write her? How would you do that? Write a quick note to her on the back of this page. Tell her you read the article above, thank her, and tell her what you learned from reading the article. After you correct your work, ask your teacher or your parents to send your note to Carolyn Johnson.