Tristan –genetic counseling

advertisement

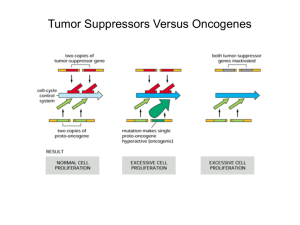

Term Paper: Genetic Counseling and Retinoblastoma Tristan Lawson BIOL 303-501 Dr. Bert Ely November 5, 2010 Retinoblastoma is the most common intraocular malignancy in children and originates in the cells of the retina. About 1 in every 15,000 to 20,000 births involves a child with retinoblastoma. Retinoblastoma develops rapidly and can cause blindness if not corrected quickly. Luckily, about 9 out of every 10 cases is cured through treatment options such as cryotherapy, chemotherapy, laser surgery, and radiation therapy. However, some of the treatments for the cancer can cause serious side effects such as vision problems. Also, children with retinoblastoma are more likely to develop secondary cancers. Retinoblastoma can be unilateral, bilateral, or in rare cases trilateral where it affects both eyes and the pineal gland. The cause of retinoblastoma can either be genetic or non-genetic. Genetic retinoblastoma is caused by a mutation on chromosome 13 and is more likely to be bilateral. Non-genetic retinoblastoma is caused by a random copy mistake during cell division in early fetal development. Because retinoblastoma is a fairly common genetic disorder with lasting effects, several studies have been done that investigate the physical or psychological limitations that retinoblastoma leads to and the role of genetic counseling in regards to retinoblastoma and decision making (Dommeringa et al., 2010). The decision by the parents to be tested to see if they are carriers or have a child who may be at risk tested is very important. However, different factors influence whether the parents utilize these testing services. In the study “RB1 genetic testing as a clinical service,” this decision is examined (Cohen et al., 2010). Families in the U.S. who had RB1 testing done in Boston were sent a survey asking them why they made their decision and how they interpreted the results. According to this survey, 98% of respondents were strongly influenced by their physician to undergo the testing. This result shows that physicians have a huge influence over their patients and should be informing them of available and prudent options. Another interesting aspect of this study was that most respondents correctly stated their results, but one mother stated that her child’s results were negative when they were actually positive (Cohen et al., 2010). Physicians and genetics counselors need to be absolutely certain that their patients understand the results. Also, the study revealed that patients who sought RB1 testing were well educated and in a middle to high socioeconomic class (Cohen et al., 2010), suggesting that less educated and poorer families are not able to afford or are not as aware of testing options. Care must be taken in the future to ensure that all children are given equal access to testing options. Reproductive decisions are very complicated for couples where one or both of the prospective parents are affected by retinoblastoma. Also, if neither parent has retinoblastoma but a previous child has retinoblastoma, the decision is even more complicated and emotional. Genetic counseling is the process where a genetic counselor explains the risks, complications, and probability of a heritable disorder in order to help couples with retinoblastoma as well as helping people with retinoblastoma deal with their disease. The study “Reproductive decision-making: a qualitative study among couples at increased risk of having a child with retinoblastoma” gauged how couples perceived the risk of passing on retinoblastoma to their children (Dommeringa et al., 2010). Couples interpreted the statistical probability of passing on a genetic disorder based on their personal experiences. If a couple had already had an affected child, the couple’s perceived risk was generally higher than the statistical probability. Likewise, couples that had not experienced the surgeries and screenings that accompany a child with retinoblastoma perceived their risks as lower than the actual probability. Also, when couples were making their decisions they tended to think of the child’s social life and the burden of the disease on the child and on the family as very important factors. Each couple made their own decision for different reasons, but a large majority of couples that participated in genetic counseling found it to be helpful (Dommeringa et al., 2010). In another study, an additional aspect of reproductive decision-making after genetic counseling was discussed (Kelley, 2009). This study analyzed the different decisions that couples make and focused on the choice of not choosing to do anything. Some couples that are confronted with an array of prenatal testing opportunities and options simply choose to do nothing and let nature take its course. Couples may limit tests to information only purposes, decline prenatal testing for subsequent pregnancies, or avoid future pregnancies through sterilization and other methods. In this particular study, in depth interviews were conducted during a three-year span in the rural U.S. after genetic counseling services were provided. The results showed that the choice not to take any action was selected due to lack of understanding of the options available, lack of education, a moral stance against abortion, and the feeling of being overwhelmed (Kelley, 2009). This study illustrates that genetic counseling can lead to different decisions, but certain population groups will select certain decisions more often. Another aspect of genetic counseling in regards to retinoblastoma is talking to survivors of retinoblastoma about the physical and psychological affects that the disease has had on their daily lives. This information is important not only to help the person struggling with the aftermath of retinoblastoma, but also to help future parents in reproductive decision-making by providing real life experiences. A study called “Restrictions in daily life after retinoblastoma from the perspective of survivors” focused on the perceived limitations of retinoblastoma and revealed some common trends (Van Dijk, 2009). About 55% of survivors felt that retinoblastoma had limited their lives in some way, either physically or emotionally. The most common complaint was vision impairment and depth perception. As the survivors aged, many experienced increased anxiety due to the possibility of developing a secondary tumor or passing the disease to future offspring. Another worrying trend that this particular study revealed was that 37% of survivors did not attend mainstream education, and 39% of survivors experienced learning difficulties at school related to vision or anxiety. Also, the average level of education achieved by survivors was much lower than the average level of education achieved by the general population. Around 47% of survivors also said that they were to some degree restricted in participation in sports (Van Dijk, 2009). The various statistics that this study compiled highlights that a disease is not only about life or death, it is about the quality of life. When children are made fun of for looking different, having learning disabilities, or not being as proficient at sports, it can have a negative impact on their lives and their futures. These factors must be taken into consideration when discussing topics such as reproductive decisions and other elements of genetic counseling. A developing area that genetic counseling is entering involves the new techniques of prenatal diagnosis. In prenatal diagnosis, tests are performed to determine if the fetus is affected by retinoblastoma. The parents can then decide to terminate or sustain the pregnancy. Several different issues come into play when talking about prenatal diagnosis. Many people are opposed to abortion because of moral beliefs and refuse prenatal diagnosis because the result would be irrelevant. Another issue is that some of the techniques such as chorion villi sampling are invasive techniques that can cause miscarriages and infections (Dommeringa et al., 2010). In one study, 2 couples out of the 14 participants chose to undergo prenatal diagnosis. One of the couples had a 50% chance of passing on the Rb1 gene and another had a 2% chance. The couple with the 2% chance chose to have the procedure done because they were not able to deal with another child with retinoblastoma because they were too involved with the treatment of their first affected child. Another couple in the same study chose not to undergo the procedure because they felt that choosing to sustain or abort a pregnancy was wrong, and they felt that you should be happy with the child that you get no matter what (Dommeringa et al., 2010). As prenatal diagnosis technologies develop and become safer, more and more people will need help in deciding whether to have these procedures done and how to interpret the results. For this reason, genetic counseling will play an important role in this area. Retinoblastoma and other genetic diseases are very much intertwined with genetic counseling. Genetic counseling aids couples in reproductive decisions as well as counseling survivors about the affects and limitations of their disease. Genetic counseling will also incorporate prenatal diagnosis more as the procedures become better known. Genetic counselors should learn to present more than statistics to couples. They need to understand the human element of the disease and the everyday problems that affected children will have to face. They need to empathize with their patients in order to help them make the best decision for their family. Genetic counseling is an extremely important asset for many people and the roles of genetic counselors should continue to expand. Works Cited Cohen, Jennifer G., Thaddeus P. Dryja, Katherine B. Davis, Lisa R. Diller, and Frederick P. Li. "RB1 Genetic Testing as a Clinical Service: A Follow-up Study." Medical and Pediatric Oncology 37.4 (2001): 372-78. Web. 4 Nov. 2010. Dommeringa, C. J., M. R. Van Den Heuvela, A. C. Molb, S. M. Imhofc, H. MeijersHeijboera, and L. Henneman. "Reproductive Decision-making: a Qualitative Study among Couples at Increased Risk of Having a Child with Retinoblastoma." Clinical Genetics 78 (2010): 334-41. Web. 4 Nov. 2010. Isidro, Marichelle A. "Retinoblastoma: EMedicine Ophthalmology." EMedicine Medical Reference. 21 Sept. 2010. Web. 04 Nov. 2010. <http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1222849-overview>. Kelly, Susan E. "Choosing Not to Choose: Reproductive Responses of Parents of Children with Genetic Conditions or Impairments." Sociology of Health & Illness 31.1 (2009): 81-97. Web. 4 Nov. 2010. Moll, A. C., D. J. Kuik, L. M. Bouter, W. Den Otter, P. D. Bezemer, J. W. Koten, S. M. Imhof, B. P. Kuyt, and K. E W P. Tan. "Incidence and Survival of Retinoblastoma in the Netherlands: a Register Based Study 1862-1995." British Journal of Ophthalmology 81.7 (1997): 559-62. Web. 4 Nov. 2010. Van Dijk, Jennifer, Kim J. Oostrom, Jaap Huisman, Annette C. Moll, Peggy T. CohenKettenis, Peter J. Ringens, and Saskia M. Imhof. "Restrictions in Daily Life after Retinoblastoma from the Perspective of the Survivors." Pediatric Blood & Cancer 54 (2009): 110-15. Web. 4 Nov. 2010.