10 Things To Do After A Death

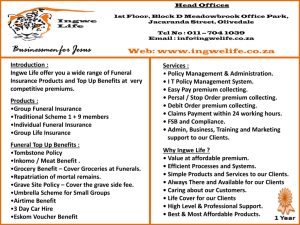

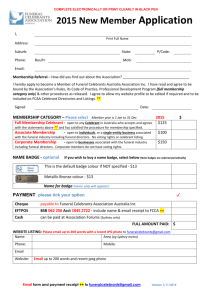

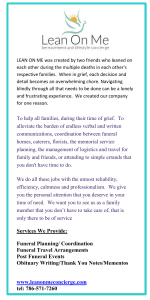

advertisement

10 Things To Do After A Death It’s a difficult time, emotions are raw and there’s a lot to organize. 1. Report the Death You must report a death to the proper authorities to begin the death certification process, which is jointly completed by a doctor or coroner and a funeral director. You’ll need multiple copies of the death certificate in order to do most of the tasks involved in disposition of the body, settling the estate, and wrapping up other affairs (like bank accounts and insurance). If you’re at a hospital, nursing home, or hospice, they will know what to do and can lead you through the proper steps, and will begin to complete the death certificate. If you’ve already been in touch with a funeral home, call them so they can get the process started. When you have no other options, call 911. Be aware that you’ll need a funeral director to claim the body for burial or cremation. If the person who died was an organ donor, inform the appropriate authorities so they can preserve the organs and prep them for donation. For Hospital and End-of-Life Facilities: Clean out the Deceased’s Residence If the person who died was living in a nursing home, assisted living facility, or hospice facility, there may be rules about how much time you have to remove the deceased’s personal property from his or her room. In order to avoid the potentially substantial charges that may result from insurance or Medicaid being discontinued. 2. Prepare To Work With A Funeral Director You need to engage a funeral director to complete the death certificate and properly transport and store the remains. Most hospitals, nursing homes, and hospices require the removal of the body within a few hours after death. Two questions you’ll need to answer: Will the body be buried or cremated? What type of funeral service will you be having? If the person who died made funeral plans before death, work directly with the particular funeral home and be aware of any pre-payments so you don’t get double charged. Speaking of money… As soon as a bank is notified of the death, any of the deceased’s accounts will be frozen until processed in probate. If you’ve been using their cash to pay their expenses, you may want to withdraw money from their bank account while you still can. 3. Types of Service: Funeral vs. Memorial vs. Graveside A funeral is when you have a service before the body is buried or cremated. A memorial service is when you have a service after the body has been buried or cremated. A graveside service is just like a funeral only it takes place on the gravesite. Regardless of the type of service, you’ll need to choose a location for the service (example: funeral home, church, synagogue, etc...) and, if appropriate, the burial (cemetery). What If The Death Occurs Far Away From Home? If the death occurred far away from where the burial will take place, you will need to work with a funeral director in the place the person died as well as a funeral director at the destination to make transportation arrangements. If you are planning a cremation followed by a memorial service at a later date, the body can be cremated in the city where the person died and the cremated remains can be shipped to you. If you are planning a cremation that will take place after a funeral service, you'll need to work with funeral homes to coordinate the transportation of the body. 4. Make Cemetery Arrangements If you are planning a burial, you'll need to decide where the burial will take place. If the person who died didn’t make cemetery arrangements (i.e., pre-purchased a plot) you will need to purchase a cemetery plot or a space in a mausoleum. The funeral home you’re working with will likely be affiliated with one or more cemeteries, and they can help you find space in one. If you belong to a church, synagogue, or other religious group, they may be affiliated with a cemetery and can help connect you to the staff there, or facilitate the sale of a plot directly. 5. Make Funeral Arrangements This is where the actual planning is a factor, for the funeral and any surrounding events for before or after the service. Choose the Type of Service You'll Have After you decide how you’re going to inter the body, you’ll need to decide if you want to have a ceremony around the interment—generally either a funeral (before the burial or cremation), a graveside service (at the interment), or memorial service (after the burial or cremation). Decide if You’ll Be Having Any Pre- or Post-Service Events Pre-funeral events generally include a viewing, wake, or visitation. Post-funeral events generally include receptions or gatherings. If you will be following religious traditions, those may help dictate these events. If you plan to have surrounding events, you will need to choose when and where they will take place. Choose How the Body will Be Prepared (i.e. Open Casket) Most funeral homes will require that a body be embalmed (a method of keeping the body in good condition) if there will be a viewing before the funeral or an open casket during the funeral. Some cultures and religions feel that being able to see the person who died offers a sense of closure, while some prohibit embalming and therefore effectively prohibit open-casket ceremonies. In some cases, depending on the cause of death, the cost and challenges of preparing the body to be viewed can be too great. While some funeral homes specialize in cosmetic restoration services, others may not have the resources to sufficiently prepare the body for viewing. You must also decide what clothing you want the person who died to be buried or cremated in, along with other belongings you want to have buried with the person. If the body will be cremated, keep in mind that any objects you'd like to save as keepsakes, such as jewelry or clothing, should be removed from the body prior to cremation. 6. Choose Cremation or Burial Products If you're planning a burial, you'll need a casket and a burial vault or grave liner. If you're planning a cremation, you'll need a cremation casket and an urn. All of these products will be available at the funeral home or cremation service. If you’re looking to cut costs you can use online retailers. 7. Choose Formal Transportation Transportation via hearse will be required to move the body from the funeral location to the cemetery, and the funeral home will provide and charge for this service. Transportation may be desired to get immediate family members from the funeral location to the cemetery in a funeral procession, and the funeral home can provide and will charge for this service, though you may also drive yourself. Note: If you're working with a funeral home, the funeral director should be taking care of these arrangements. 8. Inform The Family and Write Death Notice Depending on the method of notification that you’ll be using, you may need access to the deceased’s address book or email account. As these calls can be emotionally difficult, it can be helpful to develop a script, or jot down talking points, so you make sure you provide all necessary information. Identify a point-person from each main social area of the deceased’s life (work, clubs, etc.) and ask that person to inform the other members of that group. To get the word out to a larger audience, a death notice is a paid announcement you place in a newspaper or on a website that notifies people of the death and any services that will be held. [Dig Deeper: Checklist Writing A Death Notice or Obituary] An obituary is an article written by a media outlet offering a biography of the person. Depending on the outlet, you usually have to lobby for coverage since it’s their call. Everplans Free Service: Funeral Update allows you to create a free funeral website with a personalized URL to share information about the funeral and surrounding events, notify your family and friends of the details, and update everyone at once if anything changes. 9. A Rundown of Possible Pre-Funeral Tasks Prepare Yourself: Figure out what you’ll wear to the funeral. If you need to purchase an outfit or have an outfit dry cleaned, these are tasks that someone else may be able to handle for you. Gather Personal Items: If a photograph or photographs of the person who died will be displayed at the service, collect those photos. If you will have a guestbook at the service, remember to bring the guestbook and pens. 10. Personalize the Funeral or Memorial Service & Reception Choose an Officiant: If it’s taking place in a house of worship it will be a religious leader. It could also be a funeral director, or someone who has experience directing a funeral service. Choose Speakers and Write Eulogies: Be prepared that some people may decline a request to speak. Also be prepared for requests to speak from people you did not consider. It’s entirely acceptable to decline if you feel there are enough speakers or if it would be inappropriate for other reasons. Choose Pallbearers: If any people whom you would like to have as pallbearers are not physically capable of carrying the weight of a casket, those people can be made “honorary pallbearers” and can walk beside or behind the casket. [Dig Deeper: Pallbearers] Choose Readings and/or Music: If you would like people to deliver specific readings or prayers, choose those readings. If you will have a singer, choir, or band/ensemble perform at the service, or if you will be playing music, choose the songs or music you would like to have performed. Create Programs: Funeral programs usually contain the order of the service (including the names of participants and any readings or musical pieces that are performed) as well as an obituary. If you’d like programs, the funeral home can do this for you as a cash advance. Purchase a Guestbook: Guestbooks allow the family to know who attended the funeral, and you may purchase one from the funeral home or from a stationery store. Guestbooks are usually placed at the entrance to the service venue. Checklist: Writing a Death Notice or Obituary Death notices are paid announcements in a newspaper that give the name of the person who died and details of the funeral service, as well as where donations can be made. Obituaries are articles written by a newspaper’s staff offering a detailed biography of the person who died. Death notices and obituaries can have varying amounts of information; the information you include is entirely up to you. The basic information usually included in a death notice: The full name of the person who died, including maiden name or nickname Date and location of death Cause of death (optional) Names of surviving family members (optional) Details of the funeral or memorial service (public or private); if public, date, time, and location of service Name of charity to which donations should be made Additional biographical information may be included in a death notice, such as: Date and place of birth, names of parents Date and place of marriage, and name of spouse Educational history, including schools attended and degrees or honors received Military service, including any honors or awards received Employment history, including positions held, awards received, or special achievements Membership in organizations, including religious, cultural, civic, or fraternal Special accomplishments Hobbies and interests Personality and character of the person who died 8 Reasons You Should Decline Being A Health Care Proxy Being asked to assume responsibility of another person’s health care is an incredible display of trust and an endorsement of your dependability. It can also be an incredible burden. A Health Care Proxy is the primary decision maker in the stead of incompetent patients facing life and death circumstances. They make tough choices concerning treatment options, insurance benefits and, of course, life support. According to the American Bar Association’s Commission on Law & Aging, less than one-third of the adult population has a Living Will or other Advance Directive, so naming a Health Care Proxy (a.k.a. Health Care Power of Attorney) puts the principal (the eventual patient seeking your help) ahead of most. But are you equal to the task? If you identify with one or more of the following circumstances, you might want to respectfully decline the request if you're ever asked to serve as someone's Proxy. Indecisiveness The choices made by a Health Care Proxy are seldom casual and almost always of the essence. That means making prompt decisions that hold the utmost significance without dawdling or dithering. This duty demands generals, not grunts. Speaking of which… Meekness Acting in the interests of your principal may mean fighting often intractable medical staff and family members — each with their own respective interests in the situation. Navigating these waters requires a certain measure of political deftness, but mostly stiffness of backbone to uphold the principal's decisions. Unwillingness To Pull The Plug This is the hardest decision you may have to make as Health Care Proxy, so you could be excused for wrestling with it internally when called upon. But, when envisioning such a scenario, if that wrestling match doesn’t end 100 times out of 10 with the principal's decisions as the winner — even if it means authorizing the end of that person’s life — it’s not a decision with which you should be entrusted. Hyper-Willingness To Pull The Plug Regardless of your reasons — aversion to witnessing suffering, total disregard for human life, haste to get home in time for Game of Thrones — if you’ve got an itchy life-support finger, politely decline this job offer. Frequent Travel If you’re often out of town, be it for work or tax evasion purposes, you’re probably not a good candidate for the characteristically unexpected needs of an incompetent patient. Proximity to the principal is vital to being his/her health care representative, underscoring our next reason… Distance Depending on the medical choices of the patient, the responsibilities of Health Care Proxies can drag on for weeks, months or even years. So if you don’t live within driving range of the principal, it’s going to be nigh impossible or, at best, prohibitively expensive to fulfill your obligations. Personal Objections To Certain Medical Treatments Being a Health Care Proxy means being on board for any medical treatment that comports with the principal's decisions. So if you take religious, spiritual or intellectual exception to any of the applicable procedures or medicines stipulated within them, get past it or pass on the responsibility. Differences With The Finance Power of Attorney Often a principal will name a different Power of Attorney for finance than for health care. If you, as Health Care Proxy, don’t get along with your finance counterpart, it can mean added hardship if, for instance, he/she withholds the release of funds to pay for medical expenditures you’ve already authorized. How to Be a Good Health Care Proxy If you've been named as a health care power of attorney, there are some things you should know about your new role so that you can make sure you're doing the best job you can—whether you're called upon soon or in the far future. What is a health care power of attorney? A health care power of attorney may also be called a health care proxy, agent, representative, or surrogate—whatever the title, the responsibilities are the same, and will depend on the wishes and advance directive of the person you're representing. What are my duties as health care power of attorney? In general, as a health care power of attorney you will be in charge of making health care decisions on behalf of the person you're representing in case he or she is not able to make decisions for him or herself. In other words, you will observe and speak for the person you're representing in the way he or she would have wanted. In your role as health care power of attorney, you will have the right to make the following types of decisions: Choices about medical care, including medical tests, medicine, or surgery The right to request or decline life-support treatments Choices about pain management, including authorizing or refusing certain medication or procedures Choices about where the person will receive medical treatment, including the right to move the person to another facility, hospital, or state, or to a nursing home or hospice facility The option to take legal action on the person's behalf in order to advocate for his or her health care rights and wishes The right to apply for Medicare, Medicaid, or other programs or insurance benefits on the person's behalf As a health care power of attorney you may also be responsible for fundamentally managing the person's medical care. This may include: Learning about the person's medical condition and treatment options Communicating with the person's medical team, including asking questions about the person's condition, treatments, and treatment options Reviewing the person's medical chart Communicating with the person's family about his or her condition and treatment plan Accessing and approving release of the person's medical records Requesting and coordinating second opinions or outside medical care When does my role as health care power of attorney go into effect? Technically, your duties as a health care power of attorney begin when the person you're representing loses his or her ability to make health care decisions on his or her own. (This will be determined by the person's doctor.) As soon as you're named as a health care power of attorney, though, you can begin to get prepared. How should I prepare for my role as health care power of attorney? As a health care power of attorney, your job is to advocate for the person you're representing—which means you need to know his or her wishes, beliefs, and values around life, end-of-life, and health care preferences. By learning about the person's wishes while he or she can still communicate with you, you can address any questions you might have and be prepared to responsibly care for the person if something should happen. In order to understand the health care needs of the person you're representing, it might be a good idea to get a sense of the person's medical history and conditions. Some questions to ask are: Does the person have any ongoing medical issues, such as chronic conditions? Has the person had any major surgeries in the last 15 years? Does the person have any allergies (to medicines or to other things)? Is the person currently taking any medicines or receiving any medical treatments? What medicines or treatments and for what purposes? Are there any drugs or medical treatments that the person would prefer not to recieve, and why? If you can, have a conversation with the person to learn about how he or she would like to be treated at the end of life. Does the person care more about living as long as possible (even if that might mean some physical discomfort), or being as comfortable as possible (even if that might mean a shorter life)? Does the person want to be at home at the end of life, or would he or she prefer to be in a hospital or professional care setting? Does the person have religious or spiritual values that will affect the types of care or treatments he or she would like to receive? Are there specific life-support treatments that the person knows he or she would like to receive or would not like to receive? Would the person like to have a palliative care team or hospice team care for him or her at the end of life? Are there other wishes that should be observed as the person nears the end of life, such as calling a religious leader to come visit the person, having certain music playing, or having certain friends or family members in the room? If you're both comfortable doing so, you might want to discuss possible scenarios and how the person would like to be treated in those scenarios, such as: How would the person want to be treated if he or she got an infection? Would the person want antibiotics, or not? How would the person want to be treated if he or she was diagnosed with a terminal illness? Would the person want every effort made to treat the disease, some effort made to treat the disease, or no effort made? How would the person want to be treated if he or she went into a coma? Would the person want to live in a coma for as long as possible, for a certain period of time, or not at all? How would the person want to be treated if he or she could no longer eat or drink on his or her own? Would the person want tube feeding, or not? If the person you're representing has completed a living will, you may want to read that to get a sense of the types of treatment and care the person has specified that he or she wants and does not want. Once the power of attorney goes into effect and I'm needed to care for the person I'm representing, what should I do? As soon as a doctor has determined that the person you're representing has lost his or her ability to make health care decisions on his or her own, your role goes into effect. Depending on where you live and the type of communication you've had with the person, you may be close by and very well informed about the person's condition or you may be far away and unaware. No matter what, you should try and physically get to the place where the person is being treated, whether that's a hospital, a nursing home, or the person's own home. You will be able to do your job better if you can be close by. If you cannot get to the place where the person is, try and set up a phone call with the person's primary doctor or care coordinator. As a health care power of attorney, there are two main things you'll need to figure out: 1. What is the person's medical situation? You should talk to the person's doctor to learn about the person's medical situation and learn the facts. Does the person's medical condition have a name? If not, what could could be some possible medical conditions that he or she has? Do tests need to be done in order to figure out what the person's condition is? Will the outcome of the tests make a difference in how the person is medically treated? If not, is there a reason for doing the tests? What are the symptoms that the person is experiencing or displaying? What is being done to alleviate those symptoms? Is this treatment consistent with the person's wishes? What is the usual course of this disease? Is a doctor who specializes in this disease involved in treating the person? If not, should a specialist be brought in? 2. What are the person's treatment options? Based on the facts of the person's medical situation, the doctor can talk with you about the options for treatment, the benefits and disadvantages of each treatment option, and the best choices considering the person's condition and wishes. For each treatment option, you might want to consider: What is the goal of this treatment? What is the likelihood that this treatment will be successful—and what does success mean? Does this definition of success correspond with the person's values? What are the side effects of this treatment? How will the treatment and the side effects affect the person's quality of life? If we try this treatment option and it doesn't seem to be working, how do we decide to stop trying? What would the person I'm representing want me to do in this situation? Communicating with the family As the legally appointed health care power of attorney, you have the right to make decisions on your own. However, you may want to consult with the person's family to get their perspective. Creating an environment of communication where people know what's going on and feel like a part of the process can be important, and can help build a strong sense of agreement at a difficult emotional time.