2014 Self-Study - College of Public Health

advertisement

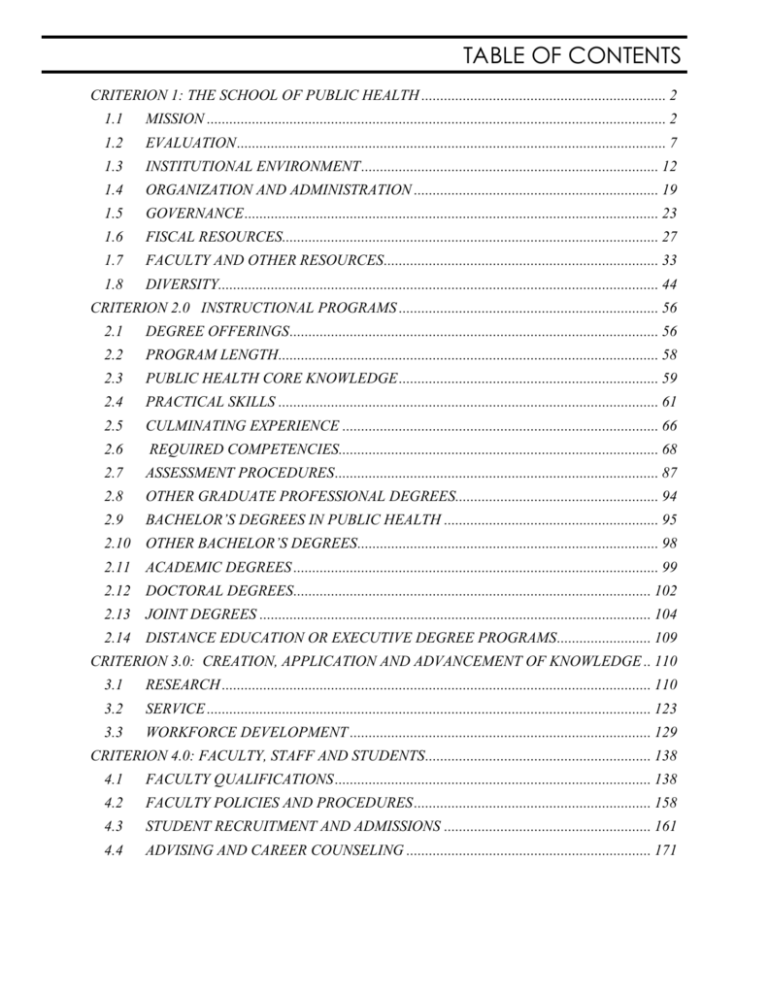

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CRITERION 1: THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH ................................................................. 2

1.1

MISSION .......................................................................................................................... 2

1.2

EVALUATION .................................................................................................................. 7

1.3

INSTITUTIONAL ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................... 12

1.4

ORGANIZATION AND ADMINISTRATION ................................................................. 19

1.5

GOVERNANCE .............................................................................................................. 23

1.6

FISCAL RESOURCES.................................................................................................... 27

1.7

FACULTY AND OTHER RESOURCES ......................................................................... 33

1.8

DIVERSITY..................................................................................................................... 44

CRITERION 2.0 INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAMS ..................................................................... 56

2.1

DEGREE OFFERINGS .................................................................................................. 56

2.2

PROGRAM LENGTH ..................................................................................................... 58

2.3

PUBLIC HEALTH CORE KNOWLEDGE ..................................................................... 59

2.4

PRACTICAL SKILLS ..................................................................................................... 61

2.5

CULMINATING EXPERIENCE .................................................................................... 66

2.6

REQUIRED COMPETENCIES..................................................................................... 68

2.7

ASSESSMENT PROCEDURES ...................................................................................... 87

2.8

OTHER GRADUATE PROFESSIONAL DEGREES...................................................... 94

2.9

BACHELOR’S DEGREES IN PUBLIC HEALTH ......................................................... 95

2.10 OTHER BACHELOR’S DEGREES ................................................................................ 98

2.11 ACADEMIC DEGREES ................................................................................................. 99

2.12 DOCTORAL DEGREES ............................................................................................... 102

2.13 JOINT DEGREES ........................................................................................................ 104

2.14 DISTANCE EDUCATION OR EXECUTIVE DEGREE PROGRAMS ......................... 109

CRITERION 3.0: CREATION, APPLICATION AND ADVANCEMENT OF KNOWLEDGE .. 110

3.1

RESEARCH .................................................................................................................. 110

3.2

SERVICE ...................................................................................................................... 123

3.3

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................ 129

CRITERION 4.0: FACULTY, STAFF AND STUDENTS ............................................................ 138

4.1

FACULTY QUALIFICATIONS .................................................................................... 138

4.2

FACULTY POLICIES AND PROCEDURES ............................................................... 158

4.3

STUDENT RECRUITMENT AND ADMISSIONS ....................................................... 161

4.4

ADVISING AND CAREER COUNSELING ................................................................. 171

CRITERION 1.0: THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

1.1

MISSION

The school shall have a clearly formulated and publicly stated mission with supporting goals,

objectives and values.

1.1.a. A clear and concise mission statement for the school as a whole.

The strategic planning process of the University of Georgia (UGA) College of Public Health

(CPH) resulted in the following mission statement:

Mission Statement

The College of Public Health at the University of Georgia promotes health in human

populations, protects the environment and prevents disease and injury in Georgia, the United

States and globally through innovative research, exemplary education and engaged service.

Since the CPH was initially accredited in 2009, the scope and interconnectedness of the three

essential modes of activity to accomplish this mission have increased due to (1) a continuous

expansion of educational programs, (2) the recruitment of faculty with a wide range of

research interests and (3) the establishment of a formal engagement office for the CPH.

1.1.b. A statement of values that guides the school.

The values of the CPH reflect the mission of the University of Georgia and its motto, “to

teach, to serve and to inquire into the nature of things.” The university seeks to foster the

understanding of and respect for cultural differences necessary for an enlightened and

educated citizenry. It seeks to provide for cultural, ethnic, gender and racial diversity in the

faculty, staff and student body. Like the university, the CPH strives to provide its students

and the community it serves with an appreciation of the critical importance of participation in

an interdependent global society. The values of quality, impact, diversity and social justice

resonate through CPH programs and are represented in our participation and leadership in

various local, national and international public health activities. The motto of the CPH, “Be

Part of the Solution,” reflects a strong emphasis placed on engagement. Students and faculty

are encouraged to actively participate in the investigation and analysis of public health

concerns with particular emphasis on developing solution-oriented interventions and lasting

strategies for prevention. The CPH has formalized its vision and core values in the following

way:

Vision Statement

The UGA College of Public Health is dedicated to excellence and innovation in instruction,

high-quality research and positive impact on communities through outreach and engagement

activities. Faculty, staff and students will collaborate fully with community and governmental

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

2

partners to improve the health and lives of the people we serve in the state of Georgia, the

nation and in other countries through our meaningful and evolving international programs

and projects.

Core Values

1. Educating and Training the Public Health Workforce: The essential product of the

College of Public Health will be trained personnel prepared as public health practitioners,

professionals and leaders who have a clear understanding of the practical and theoretical

issues that underlie their productive involvement in creating positive community health

outcomes. Graduates of the CPH will be adept at studying public health issues, engaging with

communities to solve public health problems and teaching others to do the same.

2. A Research Culture of Excellence: We are committed participants in a culture of highquality, high-impact research that attracts external funding and other resources to support

projects that improve lives in Georgia and the world. We believe that College of Public

Health research has the potential to transform public health systems and improve community

and environmental health.

3. Outreach as a Translational Mission: The CPH is committed to a translational emphasis

on delivering research outcomes to our local, regional, national and international

stakeholders. We embrace the land-grant practice of using outreach as a mechanism to

educate the populace and deliver research outcomes to the people we serve.

4. A Commitment to International Collaboration: We recognize that we live in a highly

connected world and that health problems in other countries can affect citizens beyond their

borders, including Georgians. The CPH is committed to solving those truly global public

health problems. It will seek out and establish international partnerships in research,

education and service that address global health challenges and create solutions that benefit

all.

5. Equity and Healthy Lives: The CPH will be a leader in analyzing and impacting social

determinants of health, understanding the needs of specific populations and addressing health

disparities and environmental justice issues. Appropriate policies about the availability and

access to health resources will be pursued. We will promote educational access to empower

a public health leadership that is diverse and well informed.

6. Public Health and Economic Development: Improving the health of individuals raises the

health of the community and improves economic options at multiple levels. The CPH will

have a leading role in delivering research discoveries, educational opportunities and other

university-driven outcomes that improve human and economic well-being generally.

1.1.c. One or more goal statements for each major function through which the school

intends to attain its mission, including at minimum, instruction, research and service.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

3

College of Public Health Goals

Goal 1. Exemplary Education: The College of Public Health will create and deliver

excellence in public health education.

Goal 2. Innovative Research: The College of Public Health will improve human health

through innovative research addressing the physical, mental, social and environmental

aspects of disease and injury.

Goal 3. Engaged Service: The College of Public Health will engage partners to improve

health and wellness, reduce health disparities and prevent disease and injury.

Goal 4. Structural Support: The College of Public Health will strengthen fiscal, human and

physical resources to increase capacity for teaching, research and service and to enhance the

workforce environment and culture to maximize morale and retention.

1.1.d. A set of measurable objectives with quantifiable indicators related to each goal

statement as provided in Criterion 1.1.c.

The following table offers a concise outline of CPH goals, measurable objectives and

quantifiable indicators. Appendix 1.1.d presents a more detailed matrix.

CPH Objectives and Quantifiable Indicators for Each Strategic Goal

Objective

Indicator

Goal 1: Improve Education Programs

Recruit excellent students

Student qualifications at entrance

Create quality graduate degrees

New research- and practice-oriented programs

Improve employment

Improved graduate job placement outcomes

Develop PH continuing education

Faculty involvement and program development

Goal 2: Conduct Innovative Research

Research applicability

Faculty and student research engagement

More interdisciplinary research

Multiple discipline publications and grants

Increase research activity

Increased grant submissions and publications

Goal 3: More Engaged Service

Involvement with communities

Increase research that benefits communities

More external awareness of the CPH

Increase engagement and public recognition

Goal 4: Increased Resources

Increase research grants

Funding levels and strength of research office

Create new fiscal strategies

Funding for innovative initiatives

Increase operational efficiency

HSC facilities and instructional capabilities

Enhance morale

Faculty productivity and collective outcomes

Establish a culture of excellence

Faculty concurrence about program quality

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

4

1.1.e. Description of the manner by which the mission, values, goals and objectives were

developed, including a description of how various specific stakeholder groups were

involved in their development.

Development of the CPH Mission, Values, Goals and Objectives

After achieving initial accreditation in 2009, an extensive planning process directed by an

outside consultant went into motion, resulting in the current CPH Strategic Plan (see

Appendix 1.1.e). It was developed in connection with the university-wide process that

culminated in the publication of Building on Excellence, University of Georgia 2020

Strategic Plan, approved by the University Council in November 2012. For the CPH

component, a strategic planning committee was formed to work with the consultant and

coordinate the process. Individual and focus group interviews were conducted with faculty,

students, alumni and community partners to identify strategic directions. The strategic plan

was vetted by the CPH Executive Committee (dean, associate deans, department heads and

institute/center directors) and presented to faculty for comment. The final document was

approved by vote of the faculty. This process confirmed the mission statement and developed

a set of strategic goals that form the basis of the current self-study. (See above at 1.1.a and

1.1.c.) A committee was formed subsequently to develop an evaluation plan which was

largely responsible for the list of objectives and the outcome measures approved by the

faculty and found in Section 1.1.d. The Office of the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs

took responsibility for identifying and collecting relevant data for the assessment (see

Appendix 1.2.c). More recently, a desire to strengthen the strategic plan’s vision statement

and articulate specific core values led to discussion at an executive committee retreat in

August 2013 that triggered wider deliberation. Discussions led by the associate dean for

academic affairs with CPH departments and input from faculty resulted in the text found in

Section 1.1.b focused on values.

In a sense the entire CPH, as a new and evolving institution, has been in a continuous state of

strategic planning. The creation of the mission, values, goals and objectives took place in a

wider and ongoing planning process. For example, in addition to the hours faculty have

committed to the development of a significant list of new academic degree programs

referenced in this study, and the commitment to teaching the program courses required, CPH

departments, center, institutes and the dean’s office have all been engaged in the facility

planning process required to create an entire campus of buildings for CPH activity. The

accreditation process serves as one guiding framework in a multi-layered process aimed at

building new academic programs to serve a rapidly expanding student enrollment,

developing appropriate facilities for faculty, students and the wider community and to assure

the future of an active and growing college that did not exist ten years ago.

1.1.f. Description of how the mission, values, goals and objectives are made available to

the school’s constituent groups, including the general public, and how they are

routinely reviewed and revised to ensure relevance.

Method of Dissemination of Mission, Values, Goals and Objectives

After approval by the faculty, the values, mission, goals and objectives were disseminated to

the entire CPH community via the website and newsletter. Every community partner that

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

5

participated in the process also received a copy as did our advisory committees. The mission

and goals are posted in each department. As measures were developed and validated, reports

on performance monitoring and tracking were presented on the CPH’s website and in

newsletters. Updates on these measures and performance improvement activities are shared

routinely with the Dean’s Advisory Council and the Practice Advisory Council (our external

advisory boards). At the midpoint of the strategic planning process (spring 2013), CPH

faculty reassessed the goals and objectives to determine relevance and currency. No

substantive changes were made to the mission, goals and objectives at that time, but the

vision statement has been rewritten to reflect evolving priorities with a set of clearly

articulated core values resulting from an open, college-wide process of communication with

an affirming, unanimous vote of the faculty.

1.1.g. Assessment of the extent to which this criterion is met and an analysis of the school’s

strengths, weaknesses and plans relating to this criterion.

Strengths: The CPH is anchored in a nationally ranked public university with a proven

record of outstanding academic performance. The CPH has a clearly articulated mission and

delineated goals and objectives which support public health values and ethics. The consistent

success of the CPH in terms of developing new programs, expanding enrollment rapidly,

attracting major research funding and developing new facilities and infrastructure has earned

the strong and continuing central administrative support required for success with its mission.

UGA has committed to developing excellent facilities for all CPH programs. The faculty who

have sustained the intellectual and personal effort required to plan and create a dynamic

public health program, remain committed to initiatives for continued improvement.

Challenges: The goals and objectives are ambitious and the CPH continually strains to

provide the necessary support infrastructure for a growing program. The five-year strategic

plan will expire in 2015 and envisioning the scope of future commitments will require

continued concentration on strategic issues. The unwavering commitment of the CPH to

bring all of its programs together at a single campus will face a serious challenge in terms of

creating a major new laboratory building for the final unit, the Department of Environmental

Health Science (EHS), to join the rest of the Health Sciences Campus (HSC).

Plans: The process of developing a new strategic plan will begin during the summer of 2014

by engaging faculty, staff, students and our external partners.

This criterion is met.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

6

1.2

EVALUATION

The school shall have an explicit process for monitoring and evaluating its overall efforts

against its mission, goals and objectives; for assessing the school’s effectiveness in serving its

various constituencies; and for using evaluation results in ongoing planning and decision

making to achieve its mission. As part of the evaluation process, the school must conduct an

analytical self-study that analyzes performance against the accreditation criterion defined in

this document.

1.2.a. Description of the evaluation processes used to monitor progress against objectives

defined in Criterion 1.1.d, including identification of the data systems and responsible

parties associated with each objective and with the evaluation process as a whole.

College of Public Health Evaluation and Planning

The CPH’s evaluation and planning efforts are conducted in various ways throughout the

academic cycle. The CPH complies with university-required evaluation and planning

processes that systematically assess every major aspect of the institution, including units,

programs and personnel. As directed by the Office of Institutional Effectiveness (OIE), there

is a multi-level approach to academic program assessment that includes full program review,

assessment of graduate programs and assessment of undergraduate major programs. For

example, during the 2013-2014 academic year, the Institute of Gerontology will undergo

university review, the Institute for Disaster Management (IDM) and Center for Global Health

will undergo CPH review and during the 2014-2015 year, the Department of Health

Promotion and Behavior (HPB) is scheduled to undergo review.

In addition, the CPH has developed an evaluation plan to measure the outcomes identified in

our strategic plan. The plan was initially drafted by the CPH, sent to CPH faculty for

discussion in departmental meetings and discussed at the self-study committee meetings with

the final versions sent to faculty for approval. Revisions were made at each step based on

feedback from the respective faculty and incorporated in the final document. The resulting

Table 1.2.a (based on CEPH Data Template 1.2.1) is found in Appendix 1.2.a.

Graduate Program Assessment

Since 1999, and in compliance with requirements of both the University System of Georgia

(USG) Board of Regents (BOR) and the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools

(SACS), the UGA Graduate School mandates that all graduate programs have plans and

processes in place for assessing student learning outcomes. The current system of graduate

program review is overseen by the Program Committee of the Graduate Council and operates

on a three-year cycle that culminates in the submission of a written report detailing student

learning outcomes, measurable objectives, assessment procedures and use of assessment

results for improvement. Upon completion of the review process, the chair of the Program

Committee reports to the dean of the Graduate School, who confirms satisfactory completion

status to the Associate Provost for Institutional Effectiveness. All approved reports are then

submitted to the UGA Office of Academic Planning (OAP) and can be retrieved at any time

by approved personnel. The Master of Public Health (MPH) and Doctor of Public Health

(DrPH) programs both underwent reviews and submitted Degree Reports to OAP in 2010.

The CPH master of science program in environmental health submitted a report in 2010. The

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

7

doctoral program in health promotion and behavior also submitted its last review in 2010.

The Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) programs in epidemiology and environmental health will be

reviewed in 2015 and 2016 respectively.

Graduate programs have considerable leeway in how assessment procedures are conducted in

terms of data collection strategies, the frequency of data collection and the populations

sampled. Typical sources of data, however, are students, employers and alumni. Common

approaches for collecting data include exit interviews, written surveys, certification exam

results and comprehensive assessment of competency development. For example, the

assessment plan for EHS department has five principal components: (1) a survey of

graduates and their employers at three-year intervals following graduation from our program,

(2) exit surveys or interviews of graduates since the last Assessment Report, (3) employment

status of graduates since the last Assessment Report, (4) teaching or course evaluations for

graduate courses and (5) recommended program improvements that can be developed from

the Assessment Report.

Undergraduate Program Assessment

According to criteria and policies established by the university Program Review and

Assessment Committee, the faculty responsible for each undergraduate program (i.e., major)

are required to report ongoing assessment of learning outcomes in three-year cycles. This

process is integrated with the seven-year full program review as described above and consists

of four steps: (1) defining clear learning outcomes for students in the program, (2) identifying

and implementing measures that assess whether their students attain those outcomes,

(3) analyzing the data gathered through the assessment measures for information relevant to

the program and (4) using that resulting information as the basis for program improvements.

The undergraduate majors in environmental health science (BSEH) and health promotion

(BSHP) last reported their student and degree assessment findings in 2013.

The EHS department assessment of the effectiveness of the degree program in achieving

learning objectives centers on four methods: (1) classroom data; (2) internship evaluation by

both student and employer; (3) institution of new, electronic methods for data collection for

graduates and (4) exit and internship surveys. The EHS faculty is involved in all aspects of

program assessment, and all faculty members have the opportunity to review and comment

on the assessment plan prior to its acceptance and implementation by the department. A

three-person assessment committee, including the undergraduate coordinator and two

additional EHS faculty members, is responsible for summarizing and reporting the

assessment data to faculty and for writing and submitting the overall assessment report.

The HPB department uses the following methods of assessment to monitor progress:

(1) development of a shell course for community-based service learning projects,

(2) inclusion of the Archway Public Health (discussed in Sections 1.7.h and 3.3) initiative

participants in coursework and practical experiences and (3) class projects in the final two

major classes for needs assessment and program planning with focus on evidence-based

programming. Additionally, learning objectives for the entry-level degree are focused

around seven global competency areas as outlined by the National Commission for Health

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

8

Education Credentialing (NCHEC) and adopted by the National Council for Accreditation of

Teacher Education (NCATE), which set standards for qualified teachers. HPB faculty

members are afforded the opportunity to examine all data pertinent to the undergraduate

program. Specifically, however, the undergraduate program coordinator and the

undergraduate committee are responsible for summarizing and reporting findings from the

assessment process, as well as making use of the findings toward programmatic

improvement.

Other Formal and Informal Mechanisms for Assessment

The Dean’s Advisory Council and the Practice Advisory Council, both voluntary

organizations representing key stakeholders and practitioners, provide the dean, faculty and

student affairs staff with ongoing environmental scanning and feedback on external and

practice issues related to the CPH’s development. These groups meet formally with the dean

and other CPH leaders at least once a semester. Informal discussions take place throughout

the year.

Student course assessments are conducted and evaluated at the end of each semester.

Additionally, the dean sponsors open forums with students each semester to gather feedback

about the CPH and its various degree programs. Titled “Dishing with the Dean,” these

lunchtime sessions provide an important opportunity for student interaction in an informal

atmosphere. Attendance at these sessions has increased over time and typical topics include

curricular improvements, updates on accreditation process and review and information

dissemination. Examples of changes that have resulted from these sessions include:

increasing access and available hours for the computer labs, changing day/time course

availability for the MPH core classes and working with the University Parking Services to

find alternatives for students needing faster access to the various parts of campus where

multiple college programs are located and offer instruction.

1.2.b. Description of how the results of the evaluation processes described in Criterion

1.2.a are monitored, analyzed, communicated and regularly used by managers

responsible for enhancing the quality of programs and activities.

Monitoring, Analysis, Communication and Use of Evaluation Results

All programmatic data is aggregated at the college level annually for use in the CPH’s yearend reports (for CEPH and the university). Data collection begins in October with the

individual departments or programs reporting the data to the CPH (the Office of the

Associate Dean for Academic Affairs). Data related to faculty research and engagement is

collected annually on the calendar year as faculty are reporting productivity for merit review.

All data is summarized by the CPH and shared (and discussed where appropriate) with the

Executive Committee. Where appropriate, the data is shared with faculty by the unit heads.

Concerns are then discussed at the appropriate level for effecting a change. For example,

CPH-wide matters or those involving multiple units are taken to the Executive Committee

while matters involving a specific unit are handled at the unit level.

Where appropriate, the CPH has been willing to make strategic changes in curriculum and

degree program requirements to respond to evolving needs of students and the practice

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

9

community. For example, in order to better align with community-based education

approaches, the CPH recently changed its culminating experience requirement. In instances

of student concern or suggestions for improvement, the CPH has been responsive in order to

resolve issues and make the program better.

1.2.c. Data regarding the school’s performance on each measurable objective described in

Criterion 1.1.d must be provided for each of the last three years.

Outcome Measures

Three-year data for each outcome in the evaluation plan may be found in the summary table in

Appendix 1.2.c.

1.2.d. Description of the manner in which the self-study document was developed, including

effective opportunities for input by important school constituents including

institutional officers, administrative staff, faculty, students, alumni and

representatives of the public health community.

Self-Study Document Development Process

A Reaccreditation Self-Study Committee (RSSC), chaired by Dr. Mark Wilson, associate

dean for academic affairs, guided the CPH’s self-study process. The RSSC is comprised of

ten stakeholders within the CPH representing faculty from each of the five core disciplinary

areas; one institute director, two student representatives (masters and doctoral) and one

community partner. Dr. Wilson, plus an academic professional and an administrative

specialist provided management, technical assistance, information procurement and logistical

support for the accreditation process. The RSSC members and support staff produced the

early drafts of the self-study document.

Dr. Wilson convened the RSSC monthly during the self-study process, but much of the real

work was produced by RSSC members between the formal meetings. With the guidance of

RSSC leadership, faculty and staff across the CPH provided essential content and

institutional memory to complete the self-study document. With performance data and

narrative drafts in hand, the RSSC members worked in their respective departments and

degree programs to assess outcomes and produce various written products to reflect the inner

workings of their programs and an early draft of the current document. The CPH’s Executive

Committee, comprised of unit heads and the various associate deans, undertook review,

revision and initial approval of materials developed in the accreditation process by the RSSC.

Regular accreditation discussions and, as appropriate, action items were presented at

monthly, CPH-wide faculty meetings during 2012 and 2013. The Dean’s Advisory Council,

the Practice Advisory Council and student associations participated in review and revision

activities.

During this process, the CPH sought guidance from stakeholders through distribution of the

draft self-study and development of an Internet site specifically designed for review and

comment. Over a one-month period, the dean and assistant/associate deans issued invitations

to specific audiences to provide input. In particular, the CPH’s advisory board and the

practice advisory council received such requests, as did federal, state and local practitioners,

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

10

staff, current students and alumni. Two external reviewers from CEPH-accredited peer

academic institutions also served as consultants, providing expert review and suggestions.

Feedback from all these sources was considered and incorporated into the final self-study

document.

1.2.e. Assessment of the extent to which this criterion is met and an analysis of the school’s

strengths, weaknesses and plans relating to this criterion.

Strengths: There has been strong support in the CPH for developing and implementing an

evaluation plan. CPH departments have been regularly collecting most of the needed data as

part of their normal operations.

Challenges: Systems and processes for departmental data collection require continuous

refinement and expansion as new programs come online.

Plans: Continue to refine the data collection and assessment process for existing and new

programs across all units.

This criterion is met.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

11

1.3

INSTITUTIONAL ENVIRONMENT

The school shall be an integral part of an accredited institution of higher education and shall

have the same level of independence and status accorded to professional schools in that

institution.

1.3.a. A brief description of the institution in which the school is located, and the names of

accrediting bodies (other than CEPH) to which the institution responds.

Description of the University of Georgia

The University of Georgia (UGA) is a land-grant and sea-grant university chartered in 1785

as the nation’s first state university. The university’s main campus is situated in AthensClarke County, Georgia, approximately 60 miles northeast of Atlanta, the state capitol. The

main campus is divided into four regions (north, south, west and east) and includes 313

buildings on 605 acres. In addition to its main campus, the university owns property

throughout 34 counties in Georgia totaling 43,261 acres, only 4,308 of which are situated in

Clarke County. The recently acquired 58-acre UGA Health Sciences Campus, formerly

occupied as a logistics training facility of the Navy Supply Corps School, is now being

prepared as the home for all CPH programs. Those have been housed until now in seven

different locations on and off the main campus. The HSC is in the heart of the city’s medical

services corridor and is also the home of UGA’s medical education program operated in

partnership with Georgia Regents University (GRU) in Augusta.

In 2008, UGA partnered with GRU, the state’s only public medical school, to form the

GRU/UGA Medical Partnership. This partnership led to the creation of a four-year medical

education program in Athens operated jointly by both institutions to help alleviate a

statewide shortage of physicians that threatens the health of Georgians. The first class of 40

students matriculated in 2010. The GRU/UGA Medical Partnership combines the significant

instructional and life science research resources of UGA with the medical expertise of GRU.

The combination of the College of Public Health, the local hospital systems and the medical

partnership will form the core for an expanding regional center for health sciences education,

training, research and clinical care. By 2015, all CPH units will be located at the HSC except

the EHS department, which will require construction of an appropriate laboratory facility at

the site.

To extend its reach, the university operates four satellite campuses elsewhere in the state: the

Gwinnett and Buckhead Campuses (Metropolitan Atlanta area), Griffin (Middle Georgia)

and Tifton (South Georgia). The university also operates marine research and outreach

facilities on the Georgia coast at Skidaway and Sapelo Island. The extended campuses of the

university support and advance UGA’s mission of enhancing the state’s intellectual, cultural

and environmental resources with a statewide mandate to provide higher education

opportunities. These campuses also serve as outreach sites to deliver educational programs

and opportunities to those citizens not in a position to travel to the Athens campus. Each

extended campus promotes the overall mission of UGA while offering unique elements

reflective of local need and student interest.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

12

The mission of UGA is thus shaped significantly by its statewide responsibilities for

educating and preparing an active citizenry and utilizing academic prowess to benefit the

state as a whole. While embracing its traditional land-grant mission, UGA also functions as

a leader in redefining the land-grant mission for the 21st century.

UGA is accredited by SACS and has consistently ranked among the top 25 public

universities in the nation. It is the state’s oldest, most comprehensive and most diversified

institution of higher education. Through its programs and practices, it seeks to foster the

understanding of and respect for cultural differences necessary for an enlightened and

educated citizenry. It offers cultural, ethnic, gender and racial diversity in the faculty, staff

and student body. Today, UGA has more than 34,000 students, 2,800 faculty members and

7,000 employees. The annual budget for UGA totals nearly $1.4 billion. UGA is composed

of 17 schools and colleges, plus the medical partnership. Four of these have been established

since 2005, including the College of Public Health.

UGA is consistently among the top 25 public universities according to the U.S. News and

World Report rankings (2013 U.S. News and World Report, www.usnews.com). UGA is

proud to have one of the largest and most comprehensive public service and outreach

programs conducted by an American educational institution. This reflects the university’s

commitment to serve the state of Georgia academically and through a wide range of outreach

efforts. This aspect of UGA’s heritage provides a fitting basis for a public health

commitment to improving health.

1.3.b. One or more organizational charts of the university indicating the school’s

relationship to the other components of the institution, including reporting lines.

The CPH has been led since its formation by Dr. Phillip L. Williams, who was appointed as

dean in January 2007 after a national search and multiple-candidate selection process. He

served as dean in an interim capacity prior to his permanent placement. For the dean’s

responsibilities, see 1.3.c, 1.3.c.2 and 1.4.a-b. The organization chart for UGA administration

is on line at http://president.uga.edu/uploads/documents/AdminChart_v212014.pdf.

1.3.c. Description of the school’s level of autonomy and authority regarding the following:

(1) budgetary authority and decisions relating to resource allocation

(2) lines of accountability, including access to higher-level university officials

(3) personnel recruitment, selection and advancement, including faculty and staff

(4) academic standards and policies, including establishment and oversight of

curricula

College of Public Health Autonomy and Authority: Overview

Consistent with the duties and powers given to deans of other schools and colleges, the dean

has the right, responsibility and privilege of decision making as it pertains to developing and

proposing the annual operating budget, allocating resources, procuring financial

contributions, titles, creating programs or units, recruiting faculty and staff, assigning titles

and overseeing promotion and tenure. The dean’s decision-making authority is protected by

University Council bylaws that specifically prohibit adoption of regulations that pertain to

any specific school or college without due consideration.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

13

1.3.c.(1). Budgetary authority and decisions relating to resource allocation.

Budgeting and Resource Allocation

Budgeting policies for the University System of Georgia originate with the Board of Regents

and are operationalized for UGA by the Office of the Vice President for Finance and

Administration. Annually, the Georgia General Assembly appropriates funds to the BOR as

a “lump sum” to support all institutions in the USG for the upcoming fiscal year. State funds

are then allocated by the BOR to each individual institution based on a funding formula that

reflects enrollment growth, square footage increases in facilities and other operating costs.

The university’s budget is developed after the BOR makes its allocation and provides the

university with salary increase guidelines. University unit heads establish employee salaries

for the fiscal year and budget regular employees in line-item positions. Lump-sum positions

are budgeted for temporary employees. Non-personal services are budgeted in the categories

of travel, supplies, expense and equipment.

At the university level, the Budget Office in the Office of the Vice President for Finance and

Administration has the responsibility of updating each unit’s budget, ensuring that salaries

fall within Regents’ guidelines, and balancing the total budget to the Regents’ allocation. The

budget is then submitted to the BOR for approval at the June Board meeting.

1.3.c.(2). Lines of accountability, including access to higher-level university officials.

As chief executive officer of the CPH, the dean reports directly to the senior vice president

for academic affairs and provost. The dean also interacts directly with the president on some

issues, as do all deans. An ex-officio member of the University Council, the dean actively

participates in university-level strategic planning and decision making. Similar to the status

afforded to other university deans, the CPH is independent and self-governed. The dean is

the primary officer responsible for all faculty and student activities, academic business and

resource allocation decisions directed toward accomplishing the mission of the College of

Public Health.

1.3.c.(3). Personnel recruitment, selection and advancement, including faculty and staff.

The dean has the prerogative to organize the CPH in any configuration necessary to fulfill the

organizational mission. Faculty and staff positions may be created at the dean’s discretion, in

compliance with the annual budget development cycle to which all deans are subject.

Position titles, salary ranges and hiring practices are consistent with university guidelines.

Position titles permitted by the university are first approved by the Board of Regents. Salary

ranges follow standards provided by the UGA Staff Comprehensive Pay Plan. Specific

hiring practices for faculty, classified staff and special appointments are described more fully

in Section 4.

Faculty recruitment procedures are clearly articulated in the CPH’s bylaws (Appendix 1.5.c).

To initiate faculty recruitment, unit heads must seek authorization from the dean before

appointing a search committee, which is typically chaired by a faculty member from the

recruiting unit. Search committees are composed of faculty from the recruiting unit, a faculty

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

14

representative from within the CPH (but outside the hiring unit) and at least one student

representative. Unit heads are also responsible for ensuring diversity among search

committee members and for informing the dean regarding committee membership.

Vacant full-time and administrative faculty positions are advertised on the Applicant

Clearinghouse (ACH) website that serves 35 institutions of higher education within the USG.

Whenever a vacancy is posted with ACH, an automatic search of the registrant files is

generated that cross-matches degree and discipline. A list of potentially qualified applicants

is then forwarded to the appropriate search committee. Faculty positions are also advertised

in discipline-specific journals, through the Chronicle of Higher Education website, on the

CPH’s own website and through UGA’s centralized human resources system (described

below).

All aspects of recruitment adhere to the university’s Affirmative Action/Equal Employment

Opportunity (AA/EEO) guidelines, as well as to those issued by the Office for Academic

Affairs. Position announcements typically include a statement encouraging women and

minorities to apply. Prior to release, both the dean and the EEO must approve faculty

position announcements.

The search committee screens the initial applicant pool and invites two to four candidates for

a campus visit. Candidates invited for on-campus interviews are typically required to

conduct a college-wide seminar to demonstrate teaching and/or research abilities and to meet

with faculty from the recruiting unit, the unit head, the dean and a representative from the

university president’s office (e.g., the vice president for research). The search committee

typically summarizes each candidate’s strengths and weaknesses and provides candidate

rankings for submission to the unit head who is charged with making a final selection before

seeking the dean’s approval. Unit heads must expressly obtain the dean’s permission

regarding specific employment commitments (tenure credit, teaching load, salary, etc.)

before a job offer can be formally extended. Offers for tenure-track and non-tenure-track

faculty positions are extended by the department chair. Offers for department chairs and

administrative faculty appointments (such as associate deans) are extended by the dean.

Retention of faculty is overseen by both the dean and the academic departments. Annual

reviews and promotion and tenure policies guide faculty stability in the departments as well

as their advancement from assistant, to associate to full professorship. These policies are

fully described elsewhere in Criterion 4.2 and guidelines are included in Appendix 4.2.a.

Staff Selection and Advancement

Vacant staff positions in the CPH are posted on a centralized university website, as required

by university policy. As positions are submitted for advertisement, the university notifies

departments when there is underrepresentation by minorities for specific positions. The

website includes a policy statement explaining UGA’s support of equal opportunity and

affirmative action. The hiring process typically involves a committee of at least three

persons who screen, interview and rank applicants prior to submitting a candidate list to the

unit representative responsible for hiring, who has final decision-making authority. Once

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

15

employed, staff members receive performance feedback throughout the year as needed and

undergo performance appraisal annually. Merit-based salary increases depend on state

allocation and coincide with the annual budget development cycle. Staff members may

advance both in position and salary by transferring to a new or vacant position with higher

classification, or less often, through position reclassification.

1.3.c.(4). Academic standards and policies, including establishment and oversight of

curricula.

Academic Standards

The CPH adheres to the minimum academic standards set by the university, yet has the

prerogative to develop CPH-specific policies and procedures that advance organizational

goals and objectives. The Office of Undergraduate Admissions is responsible for admitting

undergraduate applicants and transfer students. The average Scholastic Assessment Test

(SAT) score for the incoming freshman class of fall 2012 was 1,144 (compared to a national

mean of 1,010 and state mean of 977) and the average Grade Point Average (GPA) was 3.83.

The Graduate School coordinates the graduate programs of all schools and colleges within

the university and is responsible for basic admission standards for masters and doctoral

applicants. In addition to the guidelines laid forth by the Graduate School, admission

standards are set for each graduate degree by schools and colleges on campus or by academic

departments. Guidelines set by schools, colleges or academic departments can exceed, but

never be below, the Graduate School’s basic guidelines. In the case of professional degree

programs such as the MPH and the DrPH, admissions standards are formulated by the

college-level MPH and DrPH committees. Current admissions guidelines for the MPH

degree are minimum Graduate Record Examination (GRE) combined score of 1,000 for tests

taken prior to August 1, 2011, 151 verbal and 152 quantitative, respectively, and a GPA of

3.0. The incoming MPH class of 2013 has an average GRE combined score of 152V/152Q

(1160 concordance scale) and an average GPA of 3.4. Please see Appendix 1.3.c.4 for

examples of the graduate degree program application and admission process.

Curriculum Development and Oversight Policies

The CPH must receive USG approval to add or drop any degree program. A new degree,

major or interdisciplinary certificate program can only be added to the UGA curriculum after

obtaining approval by the university’s Curriculum Committee and the University Council,

followed by the president, the chancellor, and, finally, the Board of Regents. The CPH may

temporarily deactivate or reactivate an educational program, degree or major by seeking the

president’s approval, while subsequent termination or reinstatement requires the president to

obtain the additional consent of the chancellor of the USG and the BOR.

Within the CPH, curriculum oversight is provided by three committees as stipulated in the

CPH bylaws. The Curriculum and Academic Programs Committee (CAPC) exists to further

advance and coordinate curriculum development within the CPH. As such, the CAPC acts in

the name of the CPH in submitting requests for new courses and making course changes. In

addition, the CAPC is charged with making recommendations to the dean on all curriculum

matters, including all proposals regarding minors, majors, certification programs and degrees.

College-wide and generalist degree programs, the MPH and the DrPH respectively, are

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

16

overseen by separate committees that have initial curriculum development within their

purview, subject to university and system-level approvals as appropriate. These committees’

more detailed bylaws are described in Section 1.5. Specific courses are proposed and

approved through the electronic Course Approval Process, which routes course submissions

through each level of review including the department, college, Graduate School and

Curriculum Committee.

1.3.d. Identification of any of the above processes that are different for the school of public

health than for other professional schools, with an explanation.

Differences in Governance among Schools

All colleges, as far as we are aware, are treated the same in terms of their governance

relationship and administrative responsibilities by the Board of Regents, president’s and

provost’s offices. The general role and authority of the dean is the same. Because the deans

all have a good deal of autonomy in operating their colleges to meet the needs of their faculty

and students, there are naturally some individual differences in administrative structure,

resource allocation, hiring procedures and/or program details. While the CPH might differ in

detail from some colleges, it is operating under very similar expectations regarding most

internal approaches and issues.

1.3.e. If a collaborative school, descriptions of all participating institutions and delineation

of their relationships to the school.

Participating Collaborative Institutions

Not applicable.

1.3.f. If a collaborative school, a copy of the formal written agreement that establishes the

rights and obligations of the participating universities in regard to the school’s

operation.

Collaborative Institution Agreement

Not applicable.

1.3.g. Assessment of the extent to which this criterion is met and an analysis of the school’s

strengths, weaknesses and plans relating to this criterion.

Strengths: The CPH is anchored in a mature and well-respected accredited institution of

higher education. The CPH has the needed level of independence and status necessary for

operation and accreditation. The CPH has a budget allocation that is provided by the

university and has additional funding available from other sources.

Challenges: As a new college, fundraising is somewhat challenging. The state-funded

portion of the institutional budget has been decreasing for some time due to the economy.

The USG is moving from a budgeting system based on credit-hour production to one based

on programmatic outcomes. It is unclear at this time how that will be implemented and what

it will mean for the CPH.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

17

Plans: The CPH should continue to pursue additional income from non-state sources.

This criterion is met.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

18

1.4

ORGANIZATION AND ADMINISTRATION

The school shall provide an organizational setting conducive to public health learning,

research and service. The organizational setting shall facilitate interdisciplinary

communication, cooperation and collaboration that contribute to achieving the school’s public

health mission.

1.4.a. One or more organizational charts showing the administrative organization of the

school, indicating relationships among its component offices, departments divisions

or other administrative units.

Organization

The CPH is organized around the programmatic units (departments, institutes and centers)

with administrative support personnel at both the college and unit levels. All department

heads and institute/center directors report directly to the dean on the status, activities and

productivity of their respective units. All faculty in the CPH (including the dean) must have a

departmental home. The faculty affiliated with institutes or centers have a home department

in additional to the affiliation with the institute/center. The organizational chart below (Table

1.4.a) reflects this cross-affiliation, meaning faculty counted in centers and institutes are also

listed in departments.

1.4.b. Description of the roles and responsibilities of major units in the organizational

chart.

Roles and Responsibilities of the College of Public Health’s Major Units

Administration of the CPH is centered in the dean’s office. Together with his associate

deans, leadership is provided to fulfill the CPH’s teaching, research and service missions.

The Executive Committee, comprised of the department heads, the dean and associate deans,

provides strategic leadership and direction to the CPH. The full faculty act on items of

governance and policy.

As chief executive officer of the CPH, the dean is ultimately responsible for overseeing all

academic matters, developing and managing the CPH’s fiscal resources and ensuring that the

CPH is engaged in scholarship and service to better the health of Georgians and other global

citizens. To provide infrastructure for mission fulfillment, the dean has appointed associate

deans with academic affairs, research, outreach and strategic initiatives in their purview,

respectively. Each holds a faculty appointment in one of the departments, and they have

academic and research responsibilities in addition to their administrative responsibilities.

Oversight of the MPH and DrPH degree programs and certain student support functions for

all degree programs are centrally administered by the CPH. The MPH program is primarily

administered by the CPH’s graduate coordinator, Dr. Mark Wilson. This position is

supported by an academic professional, a recruitment and admissions coordinator, as well as

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

19

Table 1.4.a. 2013 Organizational Chart for the College of Public Health

As of February 2013

Reflects only state funded faculty and staff.

UGA President

1 Administrative Manager I

1 Administrative Financial Director – Vacant

1 Business Affairs Manager

1 Grant Support Manager

1 Grants Coordinator

1 Senior Accountant II

1 IT Senior Manager

1 Systems Administrative Specialist

1 IT Professional Specialist

1 Development Office Director

2 Academic Professionals

2 Administrative Specialist I

1 Administrative Associate II

UGA Provost

4 Associate Deans

CPH Dean

Departments

Environmental

Health Science

Epidemiology

and Biostatistics

Faculty

2 Professors

5 Assoc. Professors

3 Assist Professors

1 Research Scientist

Faculty

4 Professors

2 Assoc Professor

8 Assist Professors

1 Lecturer

Support Staff

1 Business Manager

1 Admin Assoc II

Support Staff

1 Research Professional

1 Scientific Comp Pro

1 Admin Assoc II

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

Health Promotion

and Behavior

Faculty

3 Professors

4 Assoc. Professors

4 Assist. Professors

1 Academic Professional

2 Instructors

1 Research Scientist

Support Staff

1 Business Manager II

1 Admin Assoc II

1 Academic Advisor III

Research Institutes & Center

Health Policy

and Management

Faculty

5 Professor

2 Assoc. Professor

5 Asst. Professors

1 Acad. Professional

1 Research Scientist

Support Staff

1 Admin Assoc II

1 Admin Assoc I

Institute of

Gerontology

Institute for

Disaster

Management

Faculty

1 Professor

1 Assoc. Professor

1 Assist. Professor

Faculty

1 Professor

1 Assist. Professor

1 Research Coordinator

Support Staff

1 Business Manager III

1 Instr. Tech Dev

Professional Associate

1 Admin Assistant II

Support Staff

2 Business Manager

2 Emergency Exercise

Coordinators

1 Emergency

Communication Manager

*all staff externally

funded.

Center for

Global Health

Faculty

1 Professor

1 Research Scientist

Support Staff

1 Student Affairs Pro

III

20

an administrative associate. The CPH also created a position of director for the DrPH

program and appointed Dr. Joel Lee in this role. Within each department, faculty members

serve as graduate coordinators and undergraduate coordinators for the various academic

degrees.

Teaching, research and service are carried out by faculty and staff within the CPH. The

academic departments, institutes and center are each directed by a unit head. These units and

their respective disciplines form the foundation of the CPH. Each is described below, in turn.

1.4.c. Description of the manner in which interdisciplinary coordination, cooperation and

collaboration occur and support public health learning, research and service.

Support of Public Health Learning

The greatest barrier to interdisciplinary collaboration has been the dispersal of the program at

multiple locations on and off the main campus. The commitment of the university to bring

all the programs together at a single campus represents a significant opportunity, and the

present small size of the CPH affords exceptional opportunity for coordination and

collaboration among faculty across departments as they assemble at the new campus.

Adjunct faculty and community-based practice leaders provide opportunity for ongoing

interface and collaboration with public health professionals across a wide range of disciplines

at the university and in the local community.

From an instructional perspective, there are college-wide committees that oversee all

programs with each department represented on the committees. All programmatic decisions

are made by these committees and approved by the curriculum and academic programs

committee (see next section), all of which are run by faculty.

From a research perspective, regular liaison meetings are held with the university’s vicepresident for research and research deans across the various colleges. These sessions provide

excellent opportunities for program and research integration. Institutes formed as part of the

UGA structure are designed to facilitate collaborative research efforts among faculty in

different departments, schools and colleges. The three institutes and one center provide

fertile ground and a welcoming academic structure for interdisciplinary work. In addition,

CPH faculty members are integrally involved with other institutes on campus, including the

Carl Vinson Institute of Government, the Institute for Behavioral Research, the Institute for

Higher Education, the Biomedical and Health Sciences Institute, the Faculty of Infectious

Diseases and the UGA Cancer Center. The CPH works closely with other UGA health

sciences programs (specifically pharmacy, veterinary medicine, social work and psychology),

and some faculty have adjunct appointments in these fields. Additionally, the CPH

leadership has standing relationships and regular meetings with the other public and private

institutions providing degrees in public health and health professions education.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

21

1.4.d. Assessment of the extent to which this criterion is met and an analysis of the school’s

strengths, weaknesses and plans relating to this criterion.

Strengths: The CPH is able to draw on well-established systems within the university and is

recognized as a change agent and catalyst for interdisciplinary collaboration and the

expansion of UGA research and instructional activity into the health sciences. The CPH has

accepted its role as a leader in the university’s effort to redefine itself as a 21st century landgrant university committed to population health. The CPH has invested in attracting

leadership with considerable years of experience and extensive public health expertise related

to cross-campus, multi-institutional and multi-national collaboration in public health research

and training.

Challenges: Interdisciplinary programs require careful delineation of unit expectations and

faculty responsibilities. Opportunities abound and positive support exists to ensure they are

realized, but they often involve a struggle to develop the full support infrastructure and stable

financial models to guarantee the stability required to succeed over the long term.

Plans: The CPH will continue to integrate units more closely into its interdisciplinary

strategies as they move to the HSC campus.

This criterion is met.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

22

1.5

GOVERNANCE

The school administration and faculty shall have clearly defined rights and responsibilities

concerning school governance and academic policies. Students shall, where appropriate, have

participatory roles in the conduct of school and program evaluation procedures, policy setting

and decision making.

1.5.a. A list of school standing and important ad hoc committees, with a statement of

charge, composition and current membership for each.

The CPH strives to have faculty actively involved in decision making. Faculty are

participants on all curricular, research and outreach committees and represent the CPH in

university-wide committees. The charge and membership for each committee is included in

Appendix 1.5.a. At present, the only ad hoc committees are the Reaccreditation Self-Study

Committee, the Diversity Committee and various faculty search committees.

Standing and Ad Hoc Committees

The CPH has the following standing committees:

Executive Committee: Consists of the dean (chair), associate/assistant deans,

academic department heads and center and institute directors.

Curriculum and Academic Programs Committee: This committee addresses selected

academic matters in the CPH and is responsible for overall academic policy of the

CPH relating to coordination of degrees, consistency across degree programs,

compliance with CEPH accreditation requirements and other educational functions as

they arise.

Undergraduate Education Committee: This committee addresses CPH undergraduate

curricula by: (1) developing curricula, ( 2) developing policies and procedures related

to instruction and advising, (3) making recommendations to CPH faculty that affect

the undergraduate majors and minors and (4) reviewing departmental and

concentration-area decisions related to the undergraduate programs.

MPH Education Committee: The purpose of this committee is to: (1) assess and

develop the curriculum, (2) develop policies and procedures, (3) oversee MPH

student admissions and student services, (4) make recommendations to faculty that

affect the MPH program and (5) review departmental/concentration-area decisions

related to the MPH.

DrPH Education Committee: The purpose of this committee is to: (1) assess and

develop the curriculum, (2) develop policies and procedures, (3) oversee DrPH

student admissions and student services, (4) make recommendations to CPH faculty

that affect the DrPH program and (5) review departmental/concentration-area

decisions related to the DrPH.

Promotion and Tenure Committee: The organization and duties of this committee are

described in Section IV of the CPH Promotion and Tenure Guidelines (see Section

1.3.c or Appendix 4.2.a in this document).

Research Advisory Committee: Chaired by the associate dean for research, the role of

the CPH Research Advisory Committee is to advise the dean on the CPH’s research

activities, opportunities and needs.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

23

Outreach and Engagement Advisory Committee: The purpose of the committee is to

advise the dean on the CPH’s outreach and engagement activities, and it is chaired by

the associate dean for outreach and engagement.

Recognition, Awards and Honors Committee: This committee is responsible for

fostering the recognition of outstanding contributions by members of the CPH and/or

the community, through teaching, research and service awards.

CEPH Reaccreditation Committee: This committee is responsible for the

development of the self-study and subsequent site visit by the CEPH review team.

Diversity Committee: This committee is responsible for reviewing and coordinating

the CPH diversity policies, procedures and activities including recruiting faculty, staff

and students. As such, this committee includes a voting member from the

administrative staff.

1.5.b. Description of the school’s governance and committee structure’s roles and

responsibilities relating to the following: general school policy development,

planning and evaluation, budget and resource allocation, student recruitment,

admission and award of degrees, faculty recruitment, retention, promotion and

tenure, academic standards and policies, including curriculum development,

research and service expectations and policies

College of Public Health Governance and Committee Structure

The CPH is governed by its bylaws through an inclusive faculty process.

Policy Development

Policies are developed through a cross-departmental inclusive process. Where appropriate,

policies flow from established university standards. All formal policies are reviewed and

adopted by the full faculty. Departments have jurisdiction over their own policies, but are

superseded by college and university policies where applicable (e.g., tenure and promotion,

and hiring procedures).

Planning

The planning process is described in detail in Criterion 1.2. Faculty, staff and students

throughout the CPH actively participate in the planning process. Planning activities related

to CPH mission, goals and degree programs involve faculty across the departments; where

appropriate, goals and planning review activities are finalized by the entire faculty.

Budget and Resource Allocation

The budget and resource allocation process is described in detail in Criterion 1.3. The CPH

participates in the university’s allocation activities. In turn, the dean engages department

chairs and administrative faculty in budget planning and oversight; once allocated, academic

resources are managed at the departmental level. Research awards are directed by the faculty

investigators.

Student Recruitment, Admission and Award of Degrees

Standards for admission and successful matriculation are established through the university

and CPH governing processes. Faculty and student services staff manage the recruitment

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

24

process in conformity with these standards and the goals of the CPH and its departments.

Degrees are awarded based on criteria established by the departments, the CPH and the

university. The criteria are published each academic year to guide the successful degree

completion of enrolling students.

Faculty Recruitment, Retention, Promotion and Tenure

The governance of faculty matters originates in the departments and is guided by the CPH

bylaws and university policy. Once recruited, annual faculty reviews guide the retention

process. Promotion and tenure processes are overseen by the CPH’s Promotion and Tenure

Committee in accordance with bylaws, discipline-specific criteria and university guidelines.

Academic Standards and Policies

Academic standards and policies are governed by department faculty and the CPH in

accordance with the CPH bylaws and university policy.

Research and Service Expectations

Faculty are apprised of research and service expectations at the time of hiring, and general

requirements are set forth in the offer letter. Over the course of faculty employment, annual

reviews provide a forum for progress measurement and professional development. The

College of Public Health is designed to be a research leader in a research university.

Therefore, expectations for research contributions are significant. New faculty are provided

with an orientation to the CPH’s goals and objectives which focus significant attention on

desired performance in the areas of research and service. All faculty participate in setting

benchmarks and conducting peer review.

1.5.c. A copy of the school’s bylaws or other policy documents that determine the rights and

obligations of administrators, faculty and students in governance of the school.

College of Public Health Bylaws

The CPH bylaws were amended and passed by the full faculty in fall 2012, after revisions

were carefully deliberated during an extended period of review. The bylaws are included in

the Appendix 1.5.c.

1.5.d. Identification of school faculty who hold membership on university committees,

through which faculty contribute to the activities of the university.

Faculty Membership on University Committees

Faculty from the CPH are actively involved in governance across the university. As an exofficio member on the University Council, the dean actively participates in university-level

strategic planning and decision making. CPH faculty members contribute to the activities of

the university in various ways. Appendix 1.5.d presents a comprehensive listing of faculty

participation in committees and groups throughout the university.

1.5.e. Description of student roles in governance, including any formal student

organizations.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

25

Student Roles in Governance

As the CPH has developed, student involvement in governance has become increasingly

important. The CPH bylaws (Article II, Section 6) formally recognize this important role:

the CPH embraces a culture of student involvement in decision making and governance. The

dean and unit heads will ensure that students are appropriately represented on standing and

ad hoc committees in the CPH and its departments. Both an MPH and a doctoral student

served on the Reaccreditation Self-Study Committee. With encouragement from the program

director, DrPH students have formed their own student governance organization and sponsor

an annual dinner meeting with faculty to discuss their graduate research activities and

interests. Additionally, students are engaged in review groups and committee work.

Students participate in some departmental committees as determined by the departments. At

a minimum, students participate in the departmental faculty meeting held monthly by each

department. This is where important strategic and curricular decisions are made for the

departments. There is understandable ambivalence among faculty about student participation

in meetings that consider faculty personnel issues or academic appeals. At the same time,

graduate students have played a very significant role as members of CPH search committees.

Each search committee includes a graduate student asked to participate at the same level of

activity as faculty in developing search materials, identifying potential candidates and in

committee assessments of candidate strengths and weaknesses. These students also typically

help elicit student input about the candidates.

A number of student organizations are active through the CPH, including the Public Health

Association at UGA, which also serves as a student chapter of the Georgia Public Health

Association (GPHA). There are student organizations for DrPH students (Pump Handle

Society), environmental health science majors (EHS student club), health promotion and

behavior majors (Future Health Promoters Club), with student membership in a wide range

of professional associations and several key honor societies. Each year a student

representative is selected to become a representative within the Student Government

Association (SGA) as well.

1.5.f. Assessment of the extent to which this criterion is met and an analysis of the school’s

strengths, weaknesses and plans relating to this criterion.

Strengths: The CPH has an effective administrative structure. Faculty play important roles

in the development and refinement of policies and procedures. Students are involved in

governance at all levels.

Challenges: Because we are a small college, a high proportion of our faculty are needed to

serve on the many college and university committees which is a burden for some.

Plans: The CPH needs to strive for consistent student participation in governance across the

departments.

This criterion is met.

College of Public Health Self-Study

February 2014

26

1.6

FISCAL RESOURCES

The school shall have financial resources adequate to fulfill its stated mission and goals, and

its instructional, research and service objectives.

1.6.a. Description of the budgetary and allocation processes, including all sources of