Advocacy Report

advertisement

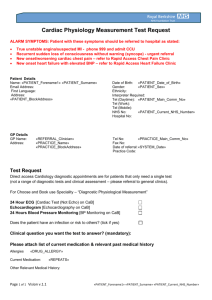

INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB i Broken Hearts Need Work Too: Increasing Participation in Cardiac Rehabilitation Post Cardiac Event Heather L. Christensen California State University Monterey Bay CHHS 302 Professor Gayle Yamauchi-Gleason April 2, 2012 INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB Table of Contents Table of Contents ……………........……….…………………………..……..…..… ii American Detriment ………………………………………..……..…….………….. 3 Hurdles to Heart Health ……………….………………………...…………….….… 3 Beneficial Outcomes of Proper Cardiac Care .………………………..………….…. 5 Promoting the Means to a Better Life ……………………...……………………….. 7 Making a Change ……………………………………...………………………….… 10 References ………………………………………… ……………………………..… 11 Appendix ………………………………………………………..…………………... 13 ii INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 3 American Detriment Nearly one in three Americans have cardiovascular disease. Currently, cardiovascular disease (CVD) or heart disease is the number one killer of both men and women in the U.S. The older a person is, the greater their chances of having a cardiac event. Arena et al. (2012) reports, “the prevalence of CVD is on the rise as a function of increased longevity and the mounting effects of cardiac risk factors that typically accumulate over a lifetime” (para. 1) Arena et al. are pointing out that there is a larger population of older adults and a longer life expectancy, which is leading to a greater number of patients with CVD. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and The Merck Company Foundation’s The State of Aging and Health in America 2007 reports that, “By 2030, the number of older Americans is expected to reach 71 million, or roughly 20% of the U.S. population” (p. 1). They also claim that due to this population shift, “healthcare spending” will increase 25% (p. 5). Price reports in her article “Cardiac Rehabilitation: Patient Referral and Enrollment” (2012) that cardiovascular disease (CVD) “costs the Canadian economy more than $22.2 billion every year in physician services, hospital costs, lost wages and decreased productivity” (p. 7). Many reports have similar statistics in the United States, therefore it is important to utilize resources that are low cost and effective. Cardiac rehabilitation (cardiac rehab) is a cost effective option for treatment of cardiac patients. Numerous studies illustrate the benefits of cardiac rehab on decreasing mortality and morbidity and the risk for a follow-on cardiac event. Braverman (2011) celebrates the fact that, “This substantial risk reduction equals or exceeds the benefits of most drugs and procedural interventions.”(p. 605). So why does referral, enrollment, and participation in cardiac rehab remain so low? Healthcare professionals play an important role in getting patients out of the hospital and into cardiac rehab. Healthcare professionals should inform cardiac patients of the importance of post-event rehabilitation (physical and emotional) in order to emphasize to patients the necessity of rehabilitation in avoiding another cardiac event and improving the overall quality of their life. Hurdles to Heart Health Numerous studies illustrate the benefits of cardiac rehab on decreasing mortality and morbidity. With the benefits well known, participation is still lacking. Farley, Wade, & Birchmore (2003) emphasize that the number of patients who participate in cardiac rehab typically ranges between 30 and 45% with a high percentage of those dropping out before finishing the cardiac rehab program (p. 205). Basically, there is a small number of cardiac patients who are participating and an even smaller number of those patients finishing their rehab program. Many barriers to patient enrollment and participation continue to exist despite the decades that have passed since they were first acknowledged. Lack of Referrals A referral must be obtained before the patient can enroll in a cardiac rehab program. Cardiac rehab referral is an American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association class I indication. This means that there is evidence and agreement that cardiac rehab is effective and there is a strong recommendation from these prominent organizations for eligible heart patients to be prescribed to cardiac rehab. Surprisingly, research indicates that a major barrier for patients is lack of physician referral. (Braverman (2011), p. 608) Brown, et al (2009) conducted a study to determine physician referral rate to cardiac rehab in hospitals that are part of the American INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 4 Heart Association’s (AHA) Get With The Guidelines (GWTG) program. Brown et al. (2009) describes the program as “a voluntary, observational data collection and quality-improvement initiative …” where hospitals “submit clinical information regarding in-hospital care and outcomes of patients hospitalized for coronary artery disease (CAD), stroke or heart failure” (p. 516). They found that only 56% of the patients that qualified for cardiac rehab were referred. Cardiac events that qualify a patient for cardiac rehab are myocardial infarction (MI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, stable angina, heart transplant, and heart valve surgery. Furthermore, Brown et al. believe that their results are overestimating the overall referral rate in the U.S. because their information is from hospitals with a high adherence to general guidelines. In other words, doctors are referring less than half of all eligible patients for cardiac rehab. The results of the study by Brown and associates (2009) discovered that patients who were younger, male, and white had a higher referral rate. Referred patients were also less likely to have Medicare, comorbidities and more likely to have had a procedure such as coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) (p. 517). In contrast, patients with dyslipidemia and smokers were more likely to be referred (Brown et al., 2009, p. 520). Balady, et al. (2011) assert that females, older adults, and minorities are less likely to be referred (p. 2952). This under referred population often times need and can benefit the most from cardiac rehab. In conjunction, Balady, et al. (2011) report, “women and minorities are significantly more likely to die within 5 years after a first MI compared with white male patients” (p.2952). Referral alone, however, does not guarantee participation. In their study, Keib, Reynolds, and Ahijevych (2010) found that perception of illness plays a large role in participation. Patients who choose not to attend CR are more apt to “down play the seriousness of their illness” and feel that they have less controllability of their illness (Everett et al., 2009, 1843). The way that healthcare professionals explain the patient’s illness and their recommendation and referral of cardiac rehab greatly influences the participation in cardiac rehab. Ades, Waldman, McCann and Weaver found that when patient perception of the physician’s referral was strong 66% of the patients participated in CR. Conversely, when the perception of the referral was weak there was only a 1.8% participation rate (as cited in Johnson, Inder, Nagle, and Wiggers, 2010, p. 32). In fact, numerous articles corroborate that a physician’s support and referral to cardiac rehab is a strong predictor of patient participation. Although this report focuses on healthcare professionals’ role in patient participation in cardiac rehab, it is also important to be aware of barriers that patients face. Patient Barriers In a study looking at factors influencing attendance to cardiac rehab conducted by Farley et al. (2003), they report that of the 165 eligible patients, only 39% attended cardiac rehab (p. 208). In other words, six in ten of the patients who are referred to cardiac rehab are not attending. In addition, the main reason that patients gave for non-attendance was that the patient felt that they could ‘deal with it on their own’ (Farley et al., 2003, p. 208). This idea of self-care demonstrates the previous discussion of the physician’s referral influencing patient participation in cardiac rehab. Braverman (2011) observes in his review that, “patient-related barriers include logistics, inadequate financial resources, lack of personal support system, and the patient’s personal preference not to exercise or participate in risk intervention” (p. 608). Factors that are associated with limited referral and enrollment in cardiac rehabilitation are detailed in table 1. INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 5 Many cardiac patients have responsibilities that they feel they need to return to. These responsibilities can distract the patient from focusing on his/her own health. As mentioned earlier, Brown and associates (2009) found that less than 50% of eligible cardiac patients are being referred to cardiac rehab and as Farley et al. (2003) reports, 39% of those that are referred are actually attending. By extension, approximately 20% of cardiac patients are reaping the benefits of cardiac rehab. Braverman (2011) emphasizes that a metaanalysis discovered, “that cardiac rehabilitation reduced recurrent myocardial infarction by 17% at 12 [months] and reduced mortality by 47% at 2 yrs” (p. 604). To put it bluntly, 80% of cardiac patients are not going to fully recover from their cardiac event. Furthermore, they are at an increased risk of having a follow-on event and/or dying within 2 years after their first cardiac event. Having just demonstrated the underutilization of cardiac rehab, the next section will discuss why cardiac rehab is important for cardiac patients in making a full recovery. Note. Balady, G., Ades, P., Bittner, V., Franklin, B., Gordon, N., Thomas, R.,…Yancy, C., (2011). Referral enrollment and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs at clinical centers and beyond: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 124. 2952. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823b21e2 INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 6 Beneficial Outcomes of Proper Cardiac Care Physical Impairments/ Morbidity/ Cardiac Event Risks When someone has a cardiac event, steps should be taken to improve their health and allow them to have a long, rich life. Keib et al. (2010) emphasize that for older adults cardiac rehab can reduce the risk of mortality by 26-31%, can modify cardiac risk factors, improve quality of life, physical function, and psychological well-being, and decrease healthcare costs associated with cardiac related rehospitalization (p. 504). Simply, cardiac rehab will decrease cardiac patients’ risk of dying from another cardiac event. It will improve their quality of life physically and mentally as well as reduce healthcare costs. Farley et al. (2003) further affirm these benefits by stating, “A comparison of risk reduction associated with behavioural therapies ([cardiac rehab] programs), and medical therapies (e.g. administration of beta blockers) found that the behavioural therapies were far superior to medical therapies in the reduction of recurrent fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarctions (MIs)…” (p. 205). It stands to reason that cardiac rehab is the best treatment for recovery post cardiac event. Recently many cardiac rehab programs have expanded to become a multidisciplinary program that emphasize making healthy lifestyle changes in patients including dietary intake, weight management and smoking cessation. However, the main focus remains on exercise. Exercise can dramatically improve survival through many mechanisms, which are represented in figure 1. Dorosz (2009) explains that exercise in cardiac rehab has been proven to be safe even for patients with a severe cardiac illness (p. 724). Braverman (2011) supports this by stating that, “…the risk of any major adverse cardiac event during cardiac rehabilitation, including myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, or death [is] one event in 60,000 to 80,000 hrs of supervised exercise.” She states that the most recognizable event to occur during rehab is arrhythmias, but emphasizes that the inclusion of a “warm-up and cool-down decreases the frequency of arrhythmias by promoting coronary perfusion” (p. 605). In short, the benefits of exercise for cardiac patients are much greater than any of the risks. INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 7 Note. Franklin, B., Goel, K., (2011, Dec. 16). Underutilization of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation: Barriers to referral, participation, and delivery. Cardiovascular Daily. Retrieved from http://my.americanheart.org/professional/General/Underutilization-of-Exercise-BasedCardiac-Rehabilitation_UCM_434567_Article.jsp#.T2_vPxwrlDQ Quality of Life and Reemployment Dorosz (2009) acknowledges that an important goal for cardiac rehab is to increase patients’ “functional capacity” and for older adults, “reduce frailty” (p. 726). Exercise training is pivotal to increasing the quality of life in cardiac patients. Dorosz (2009) further explains that with exercise training cardiac patients have less physical symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress and patients report less pain, more energy and better health in general. These benefits are even more substantial in the elderly who have a lower tolerance for exercise at the beginning of the program (p. 727). Dorosz (2009) stresses strength training can reduce the risks of falling and allow patients opportunity for independence by increasing their ability to do activities of daily living without assistance. When patients are functional they can return to activities they were doing prior to the cardiac event. INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 8 There has not been much research on the link between cardiac rehab participation and patients returning to work, but by increasing their functional capacity it can improve the likelihood of the patients returning to work. Currently of all the cardiac patients who were working before the event, only 65% go back to work (Dorosz, 2009, p.727). Programs that are designed with exercises that stimulate the patient’s work movements can be especially effective. With an increased number of people having cardiac events, there is not only personal benefits, but societal benefits to get cardiac patients back to work instead of them relying on disability. Consequently, the lack of referral to and participation in cardiac rehab could cause a major burden to the healthcare system and ultimately the American people if action is not taken. Promoting the Means to a Better Life Systematic Referral Plus a Liaison Researchers have recognized the importance of increasing referral. There have been a great deal of studies looking into the effect systematic referral has on encouraging physician’s to refer their patients to cardiac rehab. Grace et al. (2012) conducted a multicenter observational study to determine whether systematic referral provided more referrals of sub populations to cardiac rehab compared to nonsystematic referral. Grace et al. (2012) define systematic referral strategies as using electronic medical records or discharge paper work to prompt cardiac rehab referral (p. 42). Their observation was that systematic referral increased the rate of referral of all socio-demographic and clinical characteristic variables except family income. The increased referral led to higher enrollment of “patients with lower educational, of lower subjective [socioeconomic status], who were obese, and had lower activity status” (p. 43). Grace and colleagues (2012) emphasize the most important finding was more cardiac rehab enrollments of patients of low education and of lower socioeconomic status (p. 44). Although referral and enrollment were higher with systematic referral, participation in CR was similar in both groups. While these findings are preliminary and warrant further research, the essence of Grace et al.’s study is that systematic referral can increase referral of all cardiac patients regardless of sociodemographics or cardiac morbidity/ies. Grace et al. (2011) reviewed studies that looked at different systems put in place to increase referral and enrollment in cardiac rehab. They compared five different strategies: usual care (physician initiating and following through the process of referral), systematic (electronic referral), liaison (discussion of cardiac rehab by healthcare professional to the patient in the hospital), systematic referral plus liaison, and other (includes letters of encouragement to the patient) and identified their overall enrollment rates. Price (2012) summarized their findings in her article; usual care had an overall enrollment rate of 24%, liaison enrollment was 44% while systematic referral was 45%. Combined systematic referral and liaison improved enrollment with a rate of 66% (p. 8). Grace and associates (2011) determined that letters sent to the patient had the highest enrollment rate at 73%, conversely these studies are few and inconsistent (p. 19495). They emphasize that research supports the use of systematic referral with a liaison to increase referral and enrollment to cardiac rehab. Research on healthcare professionals best suited as liaison has been limited, but Arena et al. (2012) emphasize the importance of all healthcare professionals involved with cardiac patients in the hospital to encourage participation in cardiac rehab. INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 9 Health Team Support and Enthusiasm There are many healthcare professionals that are involved with cardiac patients in the hospital and they can all play a key role in informing and referring patients to cardiac rehab. Arena et al. (2012) advocate that, “consistent communication of the importance of outpatient [cardiac rehab] from multiple health professionals is likely to increase the perceived value of this lifestyle intervention by a given patient” (Sec. Defining Key Professions in the Acute Care Setting, Para. 1). To put it another way, the more cardiac rehab is mentioned to the patient the more likely they are to think that cardiac rehab is important for their recovery. Arena et al. (2012) explains the importance of each healthcare professional has in increasing a patient’s awareness and participation in cardiac rehab (CR). In the paragraphs following, the involvement in cardiac patients’ care and role in emphasizing cardiac rehab for some of the healthcare professionals who may have the most interaction with the patients are explained. Nurses are involved in many parts of the patients care during hospitalization therefore they are in a prime position to discuss the option of cardiac rehab. While more research is still needed, a study by Johnson et al. (2010) found that cardiac rehab recommendation by a cardiac rehab (CR) nurse positively correlates with patient attendance to cardiac rehab. Arena et al. (2012) urge nurses to, “discuss the reasons for obtaining a referral for outpatient CR and facilitate the process, the components of an outpatient CR program and how they pertain to the individual patient, the well-documented benefits of outpatient CR, how outpatient CR provides a safe environment for exercise, and how attending outpatient CR builds a network of resources for the future” (Sec. Defining Key Professions in the Acute Care Setting: Nursing). Although other healthcare professionals can discuss some of these points, Johnson et al. and Arena et al. are saying that their consistent interaction with the patient allows them many opportunities to continually promote cardiac rehab and increase patient attendance. Arena et al. (2012) urges all physicians, physician’s assistants (PA) and nurse practitioners involved in the care of cardiac patients to coordinate with the cardiac team in promoting CR in all eligible patients. They further explain that physicians need to ensure that a referral system is in place and the members responsible for referral are identified (Sec. Defining Key Professions in the Acute Care Setting: Physicians). As mentioned earlier physicians have a strong influence on patient’s perception of and participation in CR. Therefore it is critical that they express the importance of and encourage the participation in CR to the patient, their families and their caregivers. While nurses and physicians have a major impact on cardiac patients participation in cardiac rehab, there are other healthcare professionals on the cardiac team that may be key to increasing referral to and participation in cardiac rehab programs. Arena et al. (2012) reports that referral to a Physical therapist (PT) for “inpatient intervention and discharge assessment” determines the patient’s readiness for discharge and participation in a CR program. This inpatient assessment affords a strong base for referral to outpatient cardiac rehab. They explain that, “The inpatient PT should embrace the role of advocate for outpatient CR, educating patients on the value of participating in this important lifestyle intervention and ensuring that a referral has been secured on discharge” (Sec. Defining Professions in the Acute Care Setting: Physical Therapy). In other words Arena and associates are saying that inpatient PTs have important interactions with cardiac patients that can boost referral and enrollment in cardiac rehab. INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 10 Clinical exercise physiologists (CEPs) typically work in outpatient CR, but they can have responsibilities with an affiliating inpatient program. CEPs involved with the inpatient team can have regular contact with the patients and can provide a “link between the inpatient experience and the outpatient program.” Through their affiliation CEPs can help ensure that all eligible patients are being referred. (Arena et al., 2012, Sec. Defining Professions in the Acute Care Setting: Clinical Exercise Physiologist) It is important for any healthcare professional who is involved with cardiac patients to be educated about cardiac rehab and consistently encouraging the patient’s participation in and out patient cardiac rehab. Once the referral is issued, it is extremely important for the cardiac team to make sure that the patient is aware of the referral. The inpatient cardiac team should have a strong relationship with CR programs surrounding their area. They should understand as well as be able to inform the patient that a program can be designed to fit them, not that the patient has to fit into the program. Options: Home Based or Hospital Based As illustrated previously in table 1 a barrier for patient participation is accessibility to cardiac rehab. Patients often report that rehab doesn’t fit with their schedule or the facility is too far away. Healthcare professionals need to be aware of alternative rehab programs that can get the patients involved. Many programs are tailored towards the individual. For those patients where access to cardiac rehab is a barrier, a home based program may be beneficial to get them to participate. Balady et al. (2012) defines home based cardiac rehab as “ a structured program with clear objectives for the participants, including monitoring, follow-up visits, letters or telephone calls from staff, and the use of self-monitoring diaries” (p. 2955). In a Cochrane review, Dalal, Zawada, Jolly, Moxham, & Taylor (2010) reviewed multiple studies that looked at the effectiveness of home based cardiac rehab programs compared to center based. The outcomes Dalal et al. (2010) compared include, “exercise capacity, modifiable risk factors (BP, concentration of lipids in blood, and smoking), health related quality of life and cardiac events (including mortality, revascularization and readmission to hospital)” (Sec. Discussion, para. 1). Their review found no difference of these outcomes in patients who were in a home based program or a center based program. They also observed no significant cost difference in the two methods. Dalal et al. (2010) concede that most of the studies they reviewed only included low risk patients. Therefore, a home based cardiac rehab program is a safe, cost-effective option for stable, low risk cardiac patients. Making a Change Cardiac rehabilitation is necessary for cardiac patients. Barriers to get patients into cardiac rehab are as prominent today as they were thirty years ago. The most significant barrier is physician referral and may be the easiest one to fix. Systematic referral strategies have been proven effective at getting more heart patients to cardiac rehab. The healthcare team should work together to ensure that all eligible patients are referred to cardiac rehab. While referral alone may not increase patient participation, healthcare professionals have the power to persuade patients that cardiac rehab is important for their health. Healthcare professionals need to promote cardiac rehab and make sure all eligible patients are referred so that heart patients have INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB the best opportunity to make a full recovery post cardiac event. 11 INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 12 References Arena, R., Williams, M., Forman, D., Cahalin, L., Coke, L., Myers, J., . . . Lavie, C., (2012). Increasing referral and participation rates to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation: The valuable role of healthcare professionals in the inpatient and home health settings: A science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 125. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e318246b1e5 Balady, G., Ades, P., Bittner, V., Franklin, B., Gordon, N., Thomas, R., Tomaselli, G., & Yancy, C. (2011). Referral, enrollment and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs at clinical centers and beyond: A Presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 124, 2951-2960. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823b21e2 Braverman, D. (2011). Cardiac rehabilitation: A contemporary review. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 90, 599-611. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31821f71a6 Brown, T., Hernandez, A., Bittner, V., Cannon, C., Ellrodt, G., Liang, L.,…Fonarow, G., (2009). Predictor of cardiac rehabilitation referral in coronary artery disease patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 54, 515-521. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.080 Center for Disease Control and Prevention, The Merck Company Foundation. (2007). The state of aging and health in America 2007. Whitehouse Station, NJ: The Merck Company Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/Aging/pdf/saha_2007.pdf Dalal, H., Zawada, A., Jolly, K., Moxham, T., & Taylor, R., (2010). Home based versus centre based cardiac rehabilitation: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 340. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5631 Dorosz, J. (2009). Updates in cardiac rehabilitation. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 20. 719-736. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2009.06.006 Everett, B., Salamonson, Y., Zechin, R., & Davidson, P., (2009). Reframing the dilemma of poor attendance at cardiac rehabilitation: An exploration of ambivalence and decisional balance. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 18. 1842-1849. doi: 10.1111/j.13652702.2008.02612.x Farley, R., Wade, T., & Birchmore, L. (2003). Factors influencing attendance at cardiac rehabilitation among coronary heart disease patients. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 2, 205-212. doi:10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00060-4 Franklin, B., Goel, K., (2011, Dec. 16). Underutilization of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation: Barriers to referral, participation and delivery. Cardiovascular Daily. Retrieved from http://my.americanheart.org/professional/General/Underutilization-ofExercise-Based-Cardiac-Rehabilitation_UCM_434567_Article.jsp#.T2_vPxwrlDQ INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 13 Grace, S., Chessex, C., Arthur, H., Chan, S., Cyr, C., Dafoe, W.,…Suskin, N., (2011). Systematizing inpatient referral to cardiac rehabilitation 2010: Canadian Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Canadian Cardiovascular Society joint position paper. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 27, 192-199. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2010.12.007 Grace, S., Leung, Y., Reid, R., Oh, P., Wu, G., & Alter, D., (2012). The role of systematic inpatient cardiac rehabilitation referral in increasing equitable access and utilization. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 32, 41-47. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31823be13b Johnson, N., Inder, K., & Wiggers, J., (2010). Attendance at outpatient cardiac rehabilitation: Is it enhanced by specialist nurse referral?. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 27(4), 31-37. Retrieved from http://www.cinahl.com/cgibin/refsvc?jid=385&accno=2010717470 Keib, C., Reynolds, N., & Ahijevych, K. (2010). Poor use of cardiac rehabilitation among older adults: A self-regulatory model for tailored interventions. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care, 39, 504-511. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.11.006 Price, J. (2012). Cardiac rehabilitation: Patient referral and enrollment. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 22, 7-9. INCREASING PARTICIPATION IN CARDIAC REHAB 14 Appendix Note. Grace, S., Leung, Y., Reid, R., Oh, P., Wu, G., & Alter, D., (2012), The role of systematic inpatient cardiac rehabilitation referral in increasing equitable access and utilization. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 32, 44. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31823be13b This table illustrates the referral rate of patients to cardiac rehab based on referral strategy (systematic vs. nonsystematic) and different characteristics of the patients. It shows that systematic referral increases the referral rate of minority and low socioeconomic patients.