An electoral management body is responsible for more than

advertisement

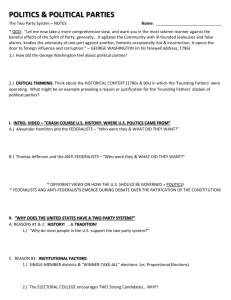

Electoral Management Bodies Charles Lasham Background It is a real pleasure for me to return to Albania and I am grateful for the opportunity to address you today. My first visit to Albania was in 1996 when you had interesting elections and I was part of a team undertaking training for observers and I was part of the international observation team also. At the time I was an election official in England and as a result of my visit I entertained members of your electoral commission in my home town of Liverpool where they experienced UK elections first hand. My last visit was last year where I spent 7 weeks or so looking at the preparations the CEC were making for your local elections, attending all meetings of the CEC during my time here, attending training of election officials in Tirana and Durres and observing the elections the elections on election day. I observed the counting of the votes – and the recounting – and met regularly with the Chair of the CEC, the deputy chair, less regularly with other members of the CEC and with other people interested in the electoral process. I have over 30 years experience in elections and I am currently working as independent electoral consultant. Between 2000 and 2010 I was the resident country representative for the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) in Moldova, Azerbaijan, Nigeria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Egypt where I worked closely with election management bodies, civil society and political parties. I am a former returning officer in the UK and European Regional Returning Officer for the North West of England. In addition to working at the highest level in UK elections, I have experience of worldwide elections having worked in 30 countries throughout the world on pre-election technical assessment missions, election studies, election assessments and advising electoral management bodies. I was s a founder member and Chairman of the UK Association of Electoral Administrators and holds the Diploma in Electoral Administration. Introduction Since the 1980s there has been a huge increase in interest in and the conduct of democratic elections throughout the world. This led to a rethink in the way elections were organized in many countries and electoral administration moved from being a low-profile activity to something which gained national and international recognition with interest from the media, election observers and the creation of national and regional associations of electoral administrators promoting democracy and the organization of credible elections. The Electoral Code reform is very important, first of all to give a clear, a technical and photographic picture of what voters want on Election Day. In the last election, of course, it was especially tricky, because it was more than a photo finish within the capital here in Tirana and led to some additional and not foreseen situations in the Electoral Code, also on what to do with all these cast ballots in different boxes. This shows that very technical questions on the placement of ballots can become very political when it comes in a close race having an influence on the result. It is just one practical example from the longer list that the OSCE/ODIHR, through Election Observation, has recommended for being revisited during the Electoral Code reform process. So now with this experience from the last elections, also the 2009 general elections, the Code, this is a tasking, will be improved, so that the Central Election Commission (CEC) will be in a better technical position to provide that service to the citizens and of course that also includes the political parties. And that should help to build the trust of the citizens in the system, that their vote counts and it is counted correctly for a truthful result whether they elect for general elections to parliament or for mayors or city parliament. It is very important now that the interest of the common citizen is being kept up, that the time is being used. You might have read or heard that the time has been extended for the ad hoc committee on Electoral Code Reform until the end of April to come up with commonly developed proposals for the future Electoral Code. It is very important to build that confidence between the parties that the CEC functions in a proper and purely technical way. That will set even more energy free for other parts of the ongoing very important reform process, which then again is very important for European integration, just to name the most important ones in my eyes: the judicial reform, the parliamentary reform.” In addition, there was interest in the machinery for organizing elections and there was, at the same time a move towards the creation of independent electoral management bodies (EMBs) responsible for all aspects of the electoral process from the registration of voters, the registration of political parties, the nomination of candidates, the organization of polling and counting and the declaration of the results. Different countries opted for different models and this paper will attempt to describe the types of EMBs throughout the world, their structures and their responsibilities. I was very fortunate to have been involved in elections in developing democracies and recall recommending the formation of electoral commissions in Eastern Europe where some of my comments were welcomed in some countries but not in others. I was also an advocate of having an Electoral Commission in the United Kingdom and I am pleased to say that we finally went down that road with the formation of a commission with the passing of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. An electoral management body is responsible for more than conducting the election on polling day. It is the custodian of the integrity and legitimacy of a key phase of the democratic process. Accordingly it must act in a transparent and impartial way and, where appropriate, consult with stakeholders on important issues, make considered policy decisions and, ideally, publish those decisions where voters and political actors to access information on the electoral process. There are three main types of electoral management bodies: 1. fully independent electoral commissions, 2. mixed model of electoral commissions that are part of government but are under the oversight of an independent body, and 3. electoral administration that is solely under the control of a government agency, usually a ministry We would expect that greater electoral commission independence would be associated with higher levels of popular confidence in the electoral process. In as much as independent electoral commissions conduct elections with greater impartiality than do arms of the government, electoral commission independence should lead citizens to perceive that the election has been conducted on a level playing field. In practice, however, independent electoral commissions are a relatively recent invention, and they tend to have been introduced in new and fragile democracies; the United Kingdom being an exception, of course. Responsibilities of EMBs The EMB usually have the responsibility for organizing all things electoral and the essential elements of this, as mentioned above, include the following: the registration of electors, compilation and publication of voter lists; the registration of political parties the nomination of candidates the conduct of the polling the counting of the votes and declaration of results Other areas of activity include boundary delimitation, voter education, media monitoring, electoral dispute regulation and campaign finance. However, each of these are sometimes handled by other organizations such as boundary commissions, civil society for voter education, media commissions for media monitoring and the courts for campaign finance which includes receipt of funds and the accounting associated with spending. It can be seen that, from the beginning to the end of the electoral process, there are many phases and activities. This is sometimes referred to as the electoral cycle. There is the pre-electoral period where planning, training, information and registration issues are handled. The electoral period itself where there is candidate nomination takes place, the election campaign, voting and the tabulation of the results. Then there is the post electoral period where a review takes place, consideration of changes or reform and strategic planning occurs. Guiding Principles of all EMBs 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Independence Impartiality Integrity Transparency Efficiency Professionalism and Service orientated The Three EMB Models The Fully Independent Electoral Commission The independent electoral commission model is where the organization of the management of elections is the responsibility of an institutionally independent body that is autonomous of the executive branch of government. Ideally the independent commission should have its own budget granted by the parliament on an annual basis which is managed by the commission. The independent commission is not answerable to the government but there are usually reporting requirements to the parliament and often commissions produce annual reports and other reports on specific issues. The commission is composed of members who are not part of the executive while in office and these may be selected from retired judges, other lawyers, political party nominees, civil society or, in the case of the United Kingdom, from people who apply to be members following an advertisement in national newspaper. Examples of independent commissions include Australia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canada, Indonesia, Iraq, Nigeria, Poland and South Africa. Often, however, the word independent is challenged by opposition parties or civil society. If “Independent” commissions are appointed by the president of a country, as is sometimes the case, then this brings into question the independence of its members. How can they be independent if appointed by the head of state who, will one day during the life of the commission be standing for election? If commissioners are all from the same political persuasion, usually the government party, then how can they act independently and make impartial decisions when considering registration of political parties, nominations from opposition candidates and other issues? The Mixed Model of Electoral Commissions This is where there are usually two component EMBs where dual structures exist. The policy, supervisory of monitoring EMB is independent of the executive branch of government and the implementation EMB is part of government and located within a ministry or local government. In the independent EMB there will be commissioners and they will be independent of the executive branch of government. Countries using this type of model include Japan, France and Spain. The Governmental Model of Electoral Administration Here the management of the electoral process is solely under the control of a government agency, usually a ministry, such as the Ministry of the Interior, for example. The budget falls under the control of the ministry, there are no commissioners and the minister would report directly to the cabinet. The implementation of the election is conducted by local authorities who are answerable to the ministry. Countries using this model include Denmark, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. International IDEA conducted a survey of election management in over 200 countries and 55% follow the independent model, 15% the mixed model and 26% the governmental model (the missing 4% are countries where they do not hold elections). Table 1: Perceptions of Electoral Fairness in 31 Elections Worldwide Country (year of election) Proportion of respondents with full confidence in the electoral process (%)* Proportion of respondents with broad confidence in the electoral process (%)** Belarus (2001) Canada (1997) Taiwan (1996) Czech Rep. (1996) Denmark (1998) Germany (1998) Great Britain (1997) Hong Kong (1998) Hong Kong (2000) Hungary (1998) Iceland (1999) Israel (1996) Japan (1996) S. Korea (2000) Lithuania (1997) Mexico (1997) Mexico (2000) Netherlands (1998) N. Zealand (1996) Norway (1997) Poland (1997) Portugal (2002) Romania (1996) Russia (1999) Slovenia (1996) Spain (1996) Spain (2000) Sweden (1998) Switzerland (1999) Ukraine (1998) USA (1996) 45.36 34.60 37.77 46.53 88.68 73.92 56.66 18.14 17.55 59.33 59.46 38.53 19.29 10.60 30.57 42.67 52.38 70.91 47.41 81.97 46.93 64.71 62.24 25.31 45.47 62.61 55.96 75.54 74.18 22.84 49.31 59.58 71.42 62.14 79.79 94.87 90.66 80.55 56.64 51.21 81.89 83.89 62.61 42.30 30.74 55.75 56.08 67.98 91.74 76.92 93.16 72.07 81.36 81.66 44.05 67.78 80.05 79.73 88.02 88.20 37.04 75.35 Mean 48.95 70.49 * Percentage of survey respondents who answered '1' to the electoral fairness question (denominator excludes cases with missing data). ** Percentage of survey respondents who answered '1' or ‘2’ to the electoral fairness question (denominator excludes cases with missing data). Extract from “Explaining Confidence in the Conduct of Elections” by Sarah Birch, University of Essex, United Kingdom

![PLEWA joint panel presentation [MS PowerPoint Document, 132.7 KB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005388913_1-9a663c909a47d520a5a627c8de595641-300x300.png)