psychological explanations of obsessive compulsive

advertisement

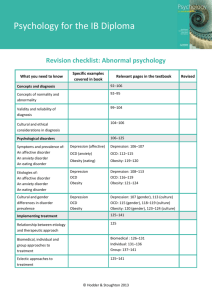

PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS OF OBSESSIVE COMPULSIVE DISORDER To read up on the psychological explanations of obsessive compulsive disorder, refer to pages 529–536 of Eysenck’s A2 Level Psychology. Ask yourself How would the psychodynamic approach explain obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)? How would the behavioural approach explain OCD? How would the cognitive approach explain OCD? What you need to know PSYCHODYNAMIC EXPLANATION BEHAVIOURAL EXPLANATION Psychodynamic explanations, beginning with Freud Evaluation Research evidence and evaluation COGNITIVE EXPLANATION Research evidence and evaluation SOCIAL EXPLANATION Life events Research evidence and evaluation Psychodynamic explanation Psychodynamic explanations of obsessive compulsive disorder originate with Freud, but have since been developed by other psychodynamic theorists. The ego (the conscious, rational mind) of patients with OCD is disturbed by their obsessions and compulsions, and this leads them to use ego defence mechanisms including isolation, undoing, and reaction formation. Isolation: patients regarding their unwanted thoughts as being alien and not belonging to them. Undoing: an undesirable impulse can be cancelled out by performing certain acts, e.g. patients who have undesirable sexual impulses may clean themselves to undo this impulse. Reaction formation: the patient adopts a lifestyle that is completely opposite from that suggested by their undesirable impulses. For example, practising celibacy to repress obsessive sexual desires. Freud argued that OCD is linked to the anal stage of development, which occurs at about 2 years of age, because during this stage children are toilet trained. A major conflict within the child between wanting to soil his or her clothes and wanting to retain faeces can occur if parents are too harsh and make the child feel dirty and ashamed. The child may deliberately soil his or her clothes as an act of rebellion. This conflict over cleanliness can lead to OCD. Freud (1949, see A2 Level Psychology page 530) also argued anxiety was linked to sexual restriction. EVALUATION OF THE PSYCHODYNAMIC EXPLANATION No scientific evidence. The explanation that conflicts over toilet training escalate into OCD has no empirical evidence to support it. This is due to the fact that Freud’s concepts cannot be operationalised because we cannot measure how much anxiety comes from sexual restriction or anger over potty training. This means none of these ideas can be tested and supported with evidence, and so the explanation lacks scientific validity. Generalisability. The explanation only seems relevant to certain obsessions and compulsions. It lacks relevance for checking or orderliness compulsions as it is not clear how these relate to toilet training or sexual constraints. Cause and effect. Any link between toilet training and OCD is just that, an association, so we cannot establish causation and we cannot say that toilet training causes OCD. Instead there could be other factors, such as personality type, that affect both toilet training and OCD. Behavioural explanation According to the behavioural explanation, fear in individuals with obsessions and compulsions is triggered by fear associated with stimuli (e.g. unwashed hands, obsessional thoughts) that are very unlikely to cause real harm. The compulsive rituals (e.g. hand washing) reduce fear and so this behaviour is reinforced or rewarded by fear reduction. RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR BEHAVIOURAL EXPLANATIONS Mowrer (1947, see A2 Level Psychology page 531) developed a two-process theory: the first process involves classical conditioning whereby a neutral stimuli becomes associated with threatening thoughts or experiences and this leads to the development of anxiety, e.g. associate shaking hands with contamination. The second process involves operant conditioning whereby the individual discovers that the anxiety is reduced by a particular behaviour, and so this becomes the compulsion. Rachman and Hodgson (1980, see A2 Level Psychology page 531) provide support for Mowrer’s theory. They found that when patients with OCD were exposed to situations triggering their obsessions this did result in a high level of anxiety, and when they performed their compulsive rituals this decreased their anxiety. EVALUATION OF BEHAVIOURAL EXPLANATIONS Face and scientific validity. The theory that the compulsive rituals reduce anxiety makes sense (face validity) and is supported by evidence (scientific validity). Exposure and response prevention therapy. These therapies are based on the behavioural explanations and are highly effective. They therefore support the validity of the explanations. The exposure and response prevention therapy involves exposing the patient to the feared stimulus while preventing them from engaging in their usual anxiety-reducing compulsive rituals. Through exposure they learn from experience that their fears and anxieties are groundless, and so their compulsive rituals aren’t needed. Reductionist. Behavioural explanations are oversimplified because they only account for learning and ignore other important aspects such as genetic factors, cognition, and evolved predisposition. Don’t explain obsessions. The behavioural explanations do not account for obsessive thinking because the behavioural approach does not account for cognition. Environmental determinism. The behavioural explanations are deterministic because they suggest that behaviour is controlled by the environment, which ignores the individual’s ability to control their own behaviour. Explain maintenance better than cause. Behavioural explanations don’t really offer a clear account of how the obsessions and rituals of OCD originate in the first place, and so do not account for cause. The behavioural explanations do explain maintenance, as they account for why the OCD persists (because the compulsions reduce anxiety) and so they account for maintenance better than they account for the cause. Nature vs. nurture. Behavioural explanations account for nurture only as, according to these, behaviour is solely a product of learning as we are born as a blank slate (tabula rasa). They ignore nature, which is a significant weakness as the evolutionary explanation suggests certain stimuli are more likely to be conditioned than others. Lack explanatory power. Behavioural explanations don’t explain why so many of the rituals of obsessive patients relate to washing and checking rather than to other possible ritualised forms of behavior; as indicated in the bullet point above, we may need to use evolutionary explanations to account for this. Multi-dimensional approach. As not all forms of OCD can be explained by conditioning, other processes must be involved, such as biological preparedness as suggested by the evolutionary approach. So to understand OCD an interaction of different factors must be considered. Cognitive explanation According to the cognitive perspective, OCD patients have an inflated sense of personal responsibility and so feel they must carry out their compulsive rituals to avoid adverse consequences, and this is their key cognitive error. Salkovskis (1996, see A2 Level Psychology page 532) explains the compulsions are based on cognitive errors. He draws from the behavioural approach, in saying that compulsions are rewarded or reinforced by immediate reduction of distress or anxiety. The carrying out of the compulsive rituals mean that OCD patients never get to test out their faulty thinking and realise there is not a dire consequence if they make a mistake. This resembles the behavioural explanation but more emphasis is given to the cognitive processes involved. RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR COGNITIVE EXPLANATIONS Buttolph and Holland (1990, see A2 Level Psychology page 532) found that 69% of female patients with obsessive compulsive disorder had the onset or worsening of symptoms during pregnancy or childbirth, which is consistent with the inflated sense of personality theory because clearly the birth of a child is an enormous responsibility for the well-being of their child. Neziroglu et al. (1992, see A2 Level Psychology page 532) found that 39% of female patients with obsessive compulsive disorder with children reported an onset of the disorder during pregnancy. Abramowitz’s review (2006, see A2 Level Psychology page 532) of the faulty cognitions shown by obsessive compulsives also supports the exaggerated sense of personal responsibility explanation because such cognitive errors include the belief that thoughts can help to cause events (called thought– action fusion), e.g. “If I wish someone dead, that increases the chances they will die”; and the belief that mistakes and imperfection are intolerable and so they have a responsibility to be perfect, e.g. “I must ensure that I always do the right thing”. RESEARCH EVIDENCE AGAINST COGNITIVE EXPLANATIONS Tallis (1995, see A2 Level Psychology page 532) challenges the inflated sense of personal responsibility explanation because, if this was the only factor involved in obsessive compulsive disorder, many more people would suffer from it. EVALUATION OF COGNITIVE EXPLANATIONS Face and scientific validity. Patients with OCD do have the faulty cognitions often surrounding their sense of personal responsibility so this explanation makes sense (face validity). It is also supported by empirical evidence and therefore has scientific validity. Self-report criticisms. Research into cognitive factors relies on self-report, e.g. the research whereby patients reported their symptoms developing during pregnancy. Such report is retrospective and so may not be accurately recalled. Furthermore, the self-report method yields subjective data as it is vulnerable to bias and distortion as a consequence of researcher effects and participant reactivity, e.g. patients may prefer to accept pregnancy as an explanation over other possible origins. Thus, the findings may be biased, and therefore not true, and so have limited validity. Lack explanatory power. The cognitive account does not explain why patients with OCD accept excessive responsibility for negative outcomes but not for positive ones. Nor does it explain why most of the compulsive rituals of these patients revolve around washing and checking, so it lacks explanatory power. Cause or effect? The evidence that negative cognitions precede the disorder is not convincing. It is entirely possible that having OCD leads to dysfunctional beliefs, and it may be that having dysfunctional beliefs doesn’t play any role in the development of OCD. Thus, the direction of effect is not clear. In addition, cause and effect cannot be established anyway from correlational evidence. Descriptive, not explanatory. The research describes the nature of the thoughts of OCD patients rather than explaining the development of OCD because it is not clear what causes the negative cognitions in the first place, other than that some are triggered by pregnancy, but this is not true of all cases. Reductionism and multi-dimensional approach. To account fully for OCD it is necessary to consider how cognition interacts with other approaches. For example, faulty thinking could be due to an interaction of biological and social factors, which are ignored by the cognitive approach and so it is too simplistic (reductionist). Social explanation: Life events There is some evidence that life events play a role in the development of OCD. RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR LIFE EVENTS Khanna, Rajendra, and Channabasavanna (1988, see A2 Level Psychology page 534) discovered that patients with OCD had experienced significantly more negative life events than healthy controls in the 6 months prior to the onset of the disorder. RESEARCH EVIDENCE AGAINST LIFE EVENTS McKeon, Roa, and Mann (1984, see A2 Level Psychology page 534) took account of whether the patient had had an anxious or non-anxious personality before the onset of OCD. Patients with an anxious personality did not experience any more life events than healthy controls whereas those with a non-anxious personality experienced three times as many life events as healthy controls in the 12 months before the onset of disorder. EVALUATION OF LIFE EVENTS Life events or an anxious personality? These findings suggest that life events or an anxious personality are possible causes of OCD. The life event may not immediately precede the disorder. Saunders et al. (1992 see A2 Level Psychology page 534) found that those who had experienced childhood sexual abuse were about five times more likely than non-abused individuals to develop OCD. Research on life events is correlational so cause and effect cannot be inferred. We do not know if the life event(s) triggered the OCD or if the OCD led to the life event. For example, individuals who are very anxious and stressed a few months before developing OCD may help to create life events such as losing their job or marital separation. Bias and distorted recall. A further weakness of the research is that it is based on retrospective self-report so internal validity may be reduced due to bias and distorted recall. Failure to contextualise. A final concern is that the life event research fails to contextualise. For some people a life event may not be stressful, e.g. a marital separation that was desired may even reduce stress, so the wider context of individual patients needs to be considered. So what does this mean? Now that we have covered psychological factors, it is no doubt clear there are numerous possible contributing factors to OCD, which of course makes it all the more difficult to explain the disorder. The diathesis–stress model offers a more comprehensive account because it combines the influence of nature (genetic predisposition, personality) and nurture (conditioning, social learning, and stress). For example, temperament is partly genetically predisposed and this may influence biochemistry, social learning, and cognitive biases. Further research is needed to understand how the various biological and psychological factors interact. The interaction of biological and psychological factors in the diathesis–stress model better accounts for individual differences, particularly in those who share genes in common, such as identical twins where one develops OCD and the other doesn’t. The diathesis–stress model can explain this because, whilst both twins will have inherited the genetic component, they may experience different learning or stressful life events. Over to you 1. Outline and evaluate one or more psychological explanation(s) of one anxiety disorder. (25 marks)