Understanding central concern of loneliness / isolation

advertisement

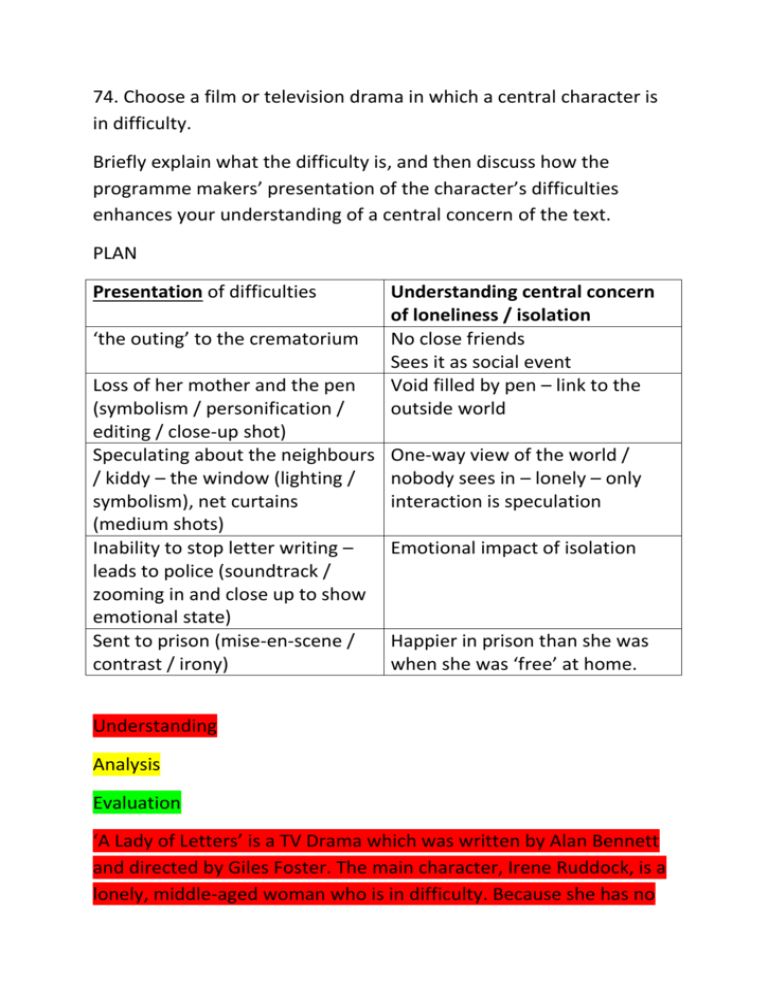

74. Choose a film or television drama in which a central character is in difficulty. Briefly explain what the difficulty is, and then discuss how the programme makers’ presentation of the character’s difficulties enhances your understanding of a central concern of the text. PLAN Presentation of difficulties ‘the outing’ to the crematorium Loss of her mother and the pen (symbolism / personification / editing / close-up shot) Speculating about the neighbours / kiddy – the window (lighting / symbolism), net curtains (medium shots) Inability to stop letter writing – leads to police (soundtrack / zooming in and close up to show emotional state) Sent to prison (mise-en-scene / contrast / irony) Understanding central concern of loneliness / isolation No close friends Sees it as social event Void filled by pen – link to the outside world One-way view of the world / nobody sees in – lonely – only interaction is speculation Emotional impact of isolation Happier in prison than she was when she was ‘free’ at home. Understanding Analysis Evaluation ‘A Lady of Letters’ is a TV Drama which was written by Alan Bennett and directed by Giles Foster. The main character, Irene Ruddock, is a lonely, middle-aged woman who is in difficulty. Because she has no close friends or family, she is lonely and ends up meddling in the lives of others. This then gets her into trouble with the police, because of the carnage her spurious allegations and damaging assumptions cause. Ultimately this results in her being sent to prison. The programme makers’ presentation of these difficulties enhances the viewer’s understanding of the central concern of the text – which is the theme of isolation and its damaging impacts. Irene’s difficulties are introduced in the opening sequence of the programme. In this sequence we see her describing her ‘outing’ to the crematorium. Her use of the word ‘outing’ suggests that she sees it as a social event instead of a time to mourn – highlighting the fact that she doesn’t have much contact with other people, and grasps any opportunity for social interaction. She also states that she didn’t know the deceased woman all that well, and makes some spurious links between them, showing us that she lacks meaningful connections to other people. The use of mise-en-scene in the opening sequence develops the idea of Irene being cut off and lonely. Her front room is show to be very drab and dull looking because of the lack of colour and this reflects her dull, uneventful life. We notice that the room only has furniture for one – with one armchair, suggesting that she never has visitors or reason to entertain others in her home. Symbolism is used to show that the loss of Irene’s mother has had a major impact on her. We see this through the use of her pen, which has incredible significance to Irene – it is her last memento of her mother (it was a gift from her before she died). The pen is emphasised through the use of a close-up shot, and editing as it is the opening shot after the screen ‘fades to black’ after the opening scene. Irene personifies the pen by referring to it as ‘a real friend’. This pen symbolises not only a link to her mother, but also her only link to the outside world as she uses it to write letters of communication. The significance of her pen helps the audience to realise just how lonely Irene is – she has no-one in her life and has to fill this void with her pen and letter-writing (we realise just how prolific her letter-writing is from the list she gives us in the opening sequence of all the correspondence she has entered into of late). The window in Irene’s front room is another symbolic feature. Lighting is used to draw our attention to it as it is the only source of light in the room, and this creates contrast with the darkness of the front room. The director also uses medium shots to show the window as the main feature in the room, and Irene is often shown sitting beside it, looking out. The window symbolises Irene’s only connection with the outside world, but it also forms a barrier between her and the rest of society – she is only an observer she doesn’t interact. This continues to help the viewer appreciate Irene’s social isolation as we realise that she desperately wants to be a part of the world outside her window, but she can’t. She spends a lot of time speculating about her neighbours and becomes concerned about the welfare of the ‘kiddy’ living opposite. We later learn that her concerns are seriously misplaced after she wrongly accuses the neighbours of child neglect. This emphasises her loneliness and isolation once more, as we realise that she doesn’t really know people and she speculates about them, rather than finding out the truth. A key sequence in the programme is when we see Irene sitting in the police station. This scene is very dramatic as we learn the real extent of Irene’s meddling and discover that she has been given a final warning by the police. Irene’s isolation is again emphasised here and we start to see how upset she is by everything that has happened. The camera slowly zooms in to a close-up, showing her emotional expression and we also hear her voice breaking with emotion as she tells us that the neighbours’ kiddy has died from leukaemia – not neglect – as she wrongly assumed. In this scene we really start to appreciate the emotional impact that Irene’s isolation has had on her, and real sympathy is evoked for her situation. She really does not seem to appreciate the impact of her interference on others until it is too late – her lack of socialisation means that she is unable to empathise or consider alternative points of view (an idea which is also emphasised through the use of the monologue narrative – where we always see things from Irene’s perspective). The climactic final sequence of the programme shows us Irene in prison, where she has been sent after failing to resist the urge to write another letter (this time making allegations about a local police officer). Contrast is used effectively in this scene to show us how different Irene’s life has become. The lighting is much brighter, Irene’s clothing is more colourful and the close-ups of her face show her expression to be much more animated and happy. The mise-enscene contrasts completely with that used in her dull, lifeless front room. This all shows how much better Irene’s life now is. Ironically she has found true happiness and freedom to express herself in a positive way in prison, where she has made new friends and taken up hobbies. Before she was isolated and lonely, but now she feels a part of something and can start to live her own life, without being preoccupied by meddling in others’ affairs. The final scene of the programme really emphasises this change in Irene as the final close-up of her shows us her smiling and saying the words, ‘I’m really happy.’ Throughout the programme Irene’s difficulties are presented to the audience. We see that she has no friends or family to support her, and that she lives an isolated and uneventful life. This all causes her to start speculating and meddling in the lives of others, which in turn lands her in trouble with the law. However, it is when we see her in the prison that we fully appreciate the damaging extent of her isolation in the outside world. She was trapped in her old existence in her front room, but now she has experienced the freedom that socialising and getting to know people brings, and we see her find true happiness in the last place you would expect. This helps the viewer to appreciate just how damaging social isolation can be for those who experience it, and reminds us how important it is to ensure that nobody in our society is overlooked, or left to suffer alone as Irene Ruddock was.