Diocese of West Yorkshire & Dales Hydraulic

advertisement

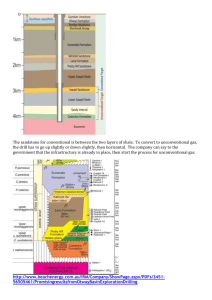

Diocese of West Yorkshire & Dales Hydraulic Fracturing (Fracking) Environment Briefing Jemima Parker, Diocesan Environment Officer. August 2015 Quick Summary Three areas in the diocese were licensed for fracking on 18th August. Each licence covers a 10km2 area. Nine other, more sensitive areas, in the diocese are being considered. The government consultation closes 29th September. Fracking is an industry that can have considerable local environmental impact causing: increased traffic; water, air and noise pollution; and effecting local wildlife. The gas and methane released by fracking are fossil fuels which, if extracted, will contribute to climate change. Further investment and commitment to exploit fossil fuels is contrary to all the scientific evidence that points to the urgent need to cut carbon and methane emissions to prevent devastating run away climate change. Photo: Cuadrilla Resources Ltd well site near Balcombe, West Sussex. As climate change is bringing both unprecedented ecosystem destruction and human suffering Christians should be moved to act compassionately and oppose fracking. Diocesan leaders and local churches should pray and consider what action to take in response to this paper. What is Fracking? Hydraulic fracturing is the process of breaking up rocks deep underground (1-3.5 km below the surface) that contain gas or oil. The deposits are reached by a small well shaft through which large quantities of water are pumped under high pressure over a period of a few weeks to break up the shale structures to release the gas. The gas is then collected over subsequent years at the well. Each well site is usually about the size of two football pitches and there may be up to 8 per square mile. Hydraulic fracturing has been a commonly used technique on North Sea oil and gas fields; however it has not been deployed onshore in the UK for shale exploitation. The largest commercial resource of shale gas deposits in the UK are expected to be in the Bowland Shale of the Pennine Basin in Lancashire and Yorkshire. Detailed maps can be viewed in the DECC report at www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/226874/BGS_DECC_Bowl andShaleGasReport_MAIN_REPORT.pdf . While there are several exploratory sites around the country, Cuadrilla Resources Ltd (UK) is the only company to have an active drill site in the UK at present at Balcome in West Sussex. What is happening with fracking in the UK and in our Diocese now? Scotland and Wales have called a moratorium on fracking in February 2015. Fracking is banned in France, Bulgaria and New York and Vermont States (USA). Moratoriums have been called in Germany, Netherlands, Quebec and Tunisia while the environmental impacts are researched. Government Licences in England The first hydraulic fracking licence was granted to Cuadrilla in 2007 in Lancashire. Since then consecutive Governments have held a series of bidding rounds to award licences to international drilling companies such as Eden Energy, UK Methane Ltd, Coastal Oil and Gas, Celtique Energie, and IGas Energy. Each licence gives permission for the company to undertake seismic surveys, exploratory drilling and then gas exploitation within a 10km2 zone, but only once planning permission for each of these activities has been obtained from the local County Council or Unitary Authority. Currently, companies have rights to drill in 176 licence areas, mostly concentrated in and around Lancashire, Cheshire, Yorkshire and Sussex, only one of which takes in one parish in the diocese, Kirkhammerton. On 18th August 2015 the government announced the first tranche of the 14th licence bidding round. 27 licences each 10km2 were granted, 3 of which are in the diocese of WY&D (see table 1 below). These can be seen on the map at www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/454361/14th_Round_Ma p_First_Tranche.pdf A further 132 10km2 areas covering more sensitive local environments are currently under consideration, the public consultation closes on 29th September. Nine of these are in or will impact on the diocese (see table 1 below) and can be viewed in detail at www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/454768/33917_HRA_App endix_E_Figs.pdf . The licences that are being held back, either contain, or are close to special environmental sites which are protected under EU law because they are home to rare species or habitats. This means the Government is obliged to carry out further consultation before formally awarding them. In July the Government issued new regulations defining “protected groundwater source areas” and “other protected areas” permitting fracking up to 50 meters away from groundwater abstraction and underneath (but not within) National Parks, area of outstanding natural beauty and World Heritage sites at a depth of at least 1200m 1. Fracking is not prohibited in or under SSSIs. Table 1: Fracking Licences in WY&D National 10km2 Grid number * Detailed map page ** Area of Licence WY&D Episcopal Area SE York Fringing Ripon Granted 2008 SE 54 E of York and Kirkhammerton Ripon Granted 2008 SE 55 Easingwold Fringing Ripon Granted 2008 SE 56 Thornscoe S Pontefract N Pontefract/ Castleford Coxwold near Thirsk Wakefield Wakefield Wakefield Licence Granted 18.8.15 Licence Granted 18.8.15 Licence Granted 18.8.15 SE 40 SE 41 SE 42 Page 28 Page 29 Page 30 Fringing Ripon Under consultation until 29.9.15 SE 57 Page 34 S Penistone Wakefield/ Huddersfield Under consultation until 29.9.15 SE 29 Page 72 N Sheffield Wakefield SE 39 Page 76 Barnsley Wakefield SE 30 Page 25 Wakefield S/ Royston Wakefield N/ Rothwell Doncaster Wakefield Under consultation until 29.9.15 Under consultation until 29.9.15 Under consultation until 29.9.15 Under consultation until 29.9.15 Under consultation until 29.9.15 E Boroughbridge within 10km Potential Zone of Impact Barnsley and Holmfirth within 10km Potential Zone of Impact Barnsley within 10km Potential Zone of Impact 10km2 Exploration area SE 31 Page 26 10km2 Exploration area SE 32 Page 27 10km2 Exploration area SE 50 Page 31 SE Pontefract Wakefield SE 51 Page 32 E Knottingley Wakefield Under consultation until 29.9.15 Under consultation until 29.9.15 SE Pontefract within 10km Potential Zone of Impact 10km2 Exploration area SE 52 Page 33 10km2 Exploration area Wakefield/ Leeds Fringing Wakefield Current licencing status Level of Impact Wetherby within 10km Potential Zone of Impact Kirkhammerton Parish within 10km2 Exploration area E Boroughbridge within 10km Potential Zone of Impact 10km2 Exploration area 10km2 Exploration area 10km2 Exploration area *See map at www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/454361/14th_Round_Ma p_First_Tranche.pdf **See map at www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/454768/33917_HRA_App endix_E_Figs.pdf Council Planning Permission and compensation Payments There is now a 16 week time limit for councils to process fracking applications. This planning guidance was issued by the Government on 13th August, shortly after Lancashire County Council’s decision in June not to grant drilling permission to Cuadrilla, to drill and frack eight wells, after several delays while the council consider more evidence. If council panning permission is not determined within this timeframe the Government will call in the application and make the decision centrally. In May 2014 the government had increased the level of compensation available to communities to £20,000 for each lateral well at fracking sites, in an attempt to lessen local opposition. The payments are on top of the existing compensation system, under which communities are to be given a lump sum of £100,000 when a test well is fracked, plus 1% of profits. What are the suggested benefits of fracking? Proponents of the fracking industry suggest that: The increase in gas production over the next 25 years will reduce UK energy bills. Others argue that gas is an international commodity and prices will continue to fluctuate globally. Photo: Workers tend to a well head during a hydraulic fracturing operation at an Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. gas well outside Rifle, in western Colorado. It will provide the UK with better energy security. This would be equally true of investment in other forms of energy generation such as renewables or nuclear power. The jobs from this industry and the tax revenue it will generate will boost the economy. Again this could also be achieved by investment in more sustainable energy industries. Increases in gas production will help the UK to move away from dirtier fossil fuels, thermal coal and oil, and act as a transition to lower carbon energy production. This disregards the fact that gas is still a fossil fuel. Transition to low carbon electricity generation can be made directly without the need for an intermediary fuel. Local communities will benefit from compensation payments from the exploration corporations. This may be at the expense of local environmental damage and health risks. What are the environmental concerns over fracking? Climate change Fracking is a fossil fuel industry. Investment in gas exploration in the UK comes at a time when we have urgent and challenging requirements facing us with regards to carbon reductions. The 2008 Climate Change Act committed the UK to reducing CO2 emissions by 50% by 2030, and by 80% by 2050. Given the radical reduction in emissions required and the need for a decarbonised electricity supply within two decades, fracking infrastructure risks being a major distraction from transitioning to a genuine zero-carbon grid. It will lock the UK into years of infrastructure investment, while it could instead be investing in renewable electricity production. Some argue that the shale gas from fracking will help the UK move away from the even dirtier electricity generation from thermal coal. A paper from Manchester University states “The argument that shale gas should be exploited as a transitional fuel in the move to a low carbon economy seems tenuous at best.” 2 The expansion of the shale gas industry in the UK is likely to increase the use of gas fired power stations and render renewable electricity generation less economic. There has already been a withdrawal of support for the renewable sector by the current government, discouraging investment and skills training. The UK Energy Research Centre states "Instead of banking on shale, UKERC recommends rapidly expanding investment in alternative low-carbon energy sources and investing in more gas storage, which would help protect consumers against short-term supply disruption and price rises" 3 Methane “Fugitive emissions” –leaks- of methane are a problem in shale gas production because methane is a potent greenhouse gas, approximately 25 times more powerful than carbon dioxide over a 100 year timescale. Emissions from fracking wells range between 4-9% of gas extracted 4. Water Contamination A multi-stage fracturing operation involves injecting water at very high pressure into the wellbore to generate fractures in the rock. Fracturing of a single well requires a considerable volume of water and, with chemical additives of up to 2% by volume, around 180-580 m3 of chemical additives (or 180580 tonnes). 2 There are two areas of concern for water pollution. Firstly, the contamination of ground water supplies. Well shafts are encased in concrete to ensure that the fracturing fluids pass through the layers of rock containing aquafers (water used for water supplies). There have been a number of instances of aquafer adulteration in the US where poor management were to blame. A wide range of toxic chemicals are used in the US, the DECC has approved the use of only 3 chemical additives in hydraulic fracturing slurries in the UK: polyacrylamide (a friction reducer); hydrochloric acid (concentrations of under 1%); and a non-toxic biocide. Secondly, possible surface water contamination from stored flowback water. One potential pollution path is from leaks on the surface through spillage. After fracturing, a proportion of the fluid returns as flowback water which not only contains the chemical additives, but is radioactive following it’s contact with deep level sedimentary rocks, which are naturally more radioactive. A study of Bowland shale revealed flowback was 500 times more radioactive than local groundwater 5, but this is apparently still within Environment Agency’s annual safe limits. Government regulation states that all flowback water storage ponds must be covered in the UK. Photo: Pools of Fracking fluid located close to a residential area. Air Pollution There is mounting evidence in the US for a range of health threats from levels of smog and of toxic air contaminants associated with drill sites. Exposure to this pollution can cause eye, nose, and throat irritation, respiratory illnesses, central nervous system damage, birth defects, cancer, or premature death 6. Air pollution stems from: diesel generating plant and from truck transport; from Silica (the main component of ‘frac sand’); chemical compounds from flowback water becoming airborne; and from nitrogen oxides released from the fracking process and volatile organic compounds reacting with sunlight to form ozone (‘smog’). Open flares for well tests are currently not permitted in the UK. Photo: Drilling near Mansfield, Texas. Noise pollution Given the high population density and the likelihood that any shale gas extraction may be located relatively close to population centres, noise pollution may be an important consideration. Activities such as drilling mean that each well pad requires around 500-1500 days (and nights) of noisy surface activity 2. Traffic The amount of water needed to drill and fracture a horizontal shale gas well generally range from about 2 million to 4 million gallons, depending on the basin and formation characteristics. This has to be transported to and subsequently removed from the well site, for decontamination. It is estimated that the construction of each well head would require between 4300-6500 truck visits. Damage to roads not suited to the levels of truck traffic associated with gas drilling has been an issue in the UK 2. Photo: Protestors and police clash again to prevent vehicles entering the fracking site at Balcombe in Sussex Landscape impacts The construction of well pads is an industrial activity and requires access roads, storage pits, tanks, drilling equipment, trucks etc. Well pads take up around 1.5-2 hectares and the well pads will be spaced between 1.25-3 per km2. To reach industry targets of 9 billion cubic metres of gas annually in the UK over 20 years 430-500 well pads would be required, covering a total land area of 140400km2. For comparison 400km2 is about equivalent to the Isle of Wight 2. Land lost may include farmland, natural habitats and amenity spaces. Earth tremors Tremors occur at a deep level when rocks are fractured. There are only three known cases of hydraulic fractured wells that induced quakes strong enough to be felt by humans at the surface. Seismic events with the potential to initiate damage (up to M 5.6) have been associated with some water disposal wells in the US. What about our Christian Response? As people of Christ we are called to take seriously our stewardship of God’s earth; to intervene to care for creation and act in the face of injustice7. We are commissioned to seek God’s Kingdom, bringing healing and restoration for the natural world 8. We must not forget the principles of land ownership and jubilee established in Leviticus 9. The earth is the Lord’s and everything in it 10. As with other aspects of our faith we may find that this means having a prophetic role in society and taking actions that are counter cultural. This is part of our proclamation of the good news of the gospel. See Appendix 1: Stewardship of Creation. Although fracking is a complex issue it is an industry that abuses God’s creation and creates injustice. Locally industrial development favours short term commercial gain by large corporations, at the expense of local people and the detriment of local land, with the potential for long term environmental damage. While some people may benefit from compensation and employment this is not widespread or sustainable. Fracking’s contribution to climate change is in many ways a more significant justice issue. The injustice from the impacts of climate change is already evident and a cause for grave concern. Those communities and individuals least able to adapt are being affected most, both in the UK and, more acutely, in less developed countries. Future generations who have not caused the damage will experience the most radical consequences of climate change. “UK plc” may benefit, over the next 25 years, from the gas produced from fracking. However, our increased carbon footprint will contribute to a global risk of tipping average global temperatures beyond a 2 0C rise, the conservative “safe” limit of global warming. See appendix 2: Climate Change a Summary. The consequences for humanity and the whole of God’s creation of climate alteration going beyond this, at an unprecedented speed, are grave. Food and water shortages, heat waves, droughts, floods, hurricanes and storms, would cause death, mass migration, exacerbate existing conflicts and ignite new ones: untold human suffering and the destruction of the incredible, intricate ecosystems that bring glory to their creator. Photo from the Climate Change, Environment and Migration Alliance If Christians remain silent about the longer term and wider impacts of fracking (or climate change in general) they ignore an abuse that must sorely grieve our compassionate and loving Lord. What could the local church do? There are many ways in which congregations can come together to bless the local community and our global neighbours while under the threat of local fracking. These include: Praying for these complex issues of environment, economy and justice. Pray for wise decisions for our Government, County Councils and discernment on what action we should take personally. Raising awareness. Making local people, businesses and other community groups aware that fracking applications or consultations are taking place and informing them of the implications of fracking. Offering a venue for public meetings. Providing a warm welcome to all. Speaking out for justice: o Taking part in the Government consultation on fracking licence areas. The current round closes 29th September 2015. o Contacting their local County Councillor or County Council Planning Committee members to express any concerns relating to fracking, such as the local impact and climate justice issues. Join or start a local community fracking action group to bring a Jesus focused and scripturally based views to a local issue. There are currently only community groups in Hebden Bridge, Harrogate and Wetherby (additionally York and Doncaster, although outside the Diocese, have groups). References 1 Department of Energy and Climate Change. The Onshore Hydraulic Fracturing (Protected Areas) Regulations 2015 www.legislation.gov.uk/id/ukdsi/2015/9780111137932 2 “Shale gas: a provisional assessment of climate change and environmental impacts” The Tyndall Centre, University of Manchester 2011 tyndall.ac.uk/sites/default/files/tyndall-coop_shale_gas_report_final.pdf 3 "A Bridge to a Low-Carbon Future? Modelling the Long-Term Global Potential of Natural Gas". www.ukerc.ac.uk UK Energy Research Centre 2014 4 Nature 493, 2013 www.nature.com/news/methane-leaks-erode-green-credentials-of-natural-gas-1.12123 5 Centre for Research into Earth Energy Systems (CeREES), Durham University www.dur.ac.uk/resources/refine/NORM24-614.pdf 6 Fracking Fumes: Air Pollution from Hydraulic Fracturing Threatens Public Health and Communities. Natural Resources Defense Council 2014 www.nrdc.org/health/files/fracking-air-pollution-IB.pdf 7 Micah 6:1-8 8 Mark 16:15, Romans 8:19 9 Psalm 24:1 10 Leviticus 25:23-24 Appendix 1: Stewardship of Creation Exploring God’s relationship with His created order should be our starting point. We need to stand back and consider Christ’s love for1 and joy in His creation. Take time to reflect on how creation primarily exists to glorify the Lord2. Consider the implications of knowing that Jesus came to bring salvation3 and reconciliation4 for the whole earth through His death and resurrection. All of creation is waiting for the fruition of the Kingdom of God, so as to be fully redeemed and restored5, just as we do as people. We have the beautiful picture in Revelation 21:1-5 of the restoration of heaven and earth where God comes to dwell with us in His renewed creation. The earth is the Lord’s and everything in it. Psalm24:1 We are temporary tenants6, not owners, of this beautiful, intricate world that God has blessed us with. He has placed us in a relationship with the natural world. We are completely dependent upon it for our basic needs of air to breath, water, food and shelter; and for more sophisticated benefits such as medicines, precious metal, radio waves or inspiration for art. In that relationship we have a responsibility for the earth, a stewardship relationship, where we are to care for other species and resources that the earth holds. However, we are all aware that this relationship between the natural world and people is damaged. We can easily see the effects of this brokenness on the land, sea and air in, say, an oil tanker spill7. In a more complex way climate change is bringing about radical damage to the whole of the earth’s systems. The atmosphere, ocean currents, coastal interfaces, polar regions and every ecosystem on the planet is experiencing unprecedentedly rapid change. Additionally our impaired relationship with creation spills over to affect our relationship with other people. The injustice of the impacts of climate change is acute8. Those communities and individuals least able to adapt are being affected most. Future generations who have not caused the damage will experience the most radical consequences of climate change. As people of Christ we are called to take seriously our stewardship of God’s earth; to intervene to care for creation and act in the face of injustice. We are commissioned to seek God’s Kingdom, bringing healing and restoration for the natural world. As with other aspects of our faith we may find that this means having a prophetic role in society and taking actions that are counter cultural. This is part of our proclamation of the good news of the gospel. “And He said to them, ‘Go into the world and proclaim the good news to the whole of creation.’” Mark 16:15 1 John 3:16 2 Psalm 19:1-5 3 John 3:17, Psalm 65:5 4 Colossians 1:20 5 Romans 8:19-23, Isaiah 43:18-21 6 Leviticus 25:23-24 7 Hosea 4:1-18 8 Micah 6:1-8 Appendix 2: Climate Change – A Summary Climate change is a present reality and it will be part of all our futures. Key facts There has been 0.85 °C global average temperature rise between 1880 and 2012. 1 Concentrations of greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) now substantially exceed the highest concentrations recorded in ice cores during the past 800,000 years. The rate of increase of these gases in the past century is unprecedented in the past 22,000 years. 2 Current Climate Change Outcomes Changes in many extreme weather and climate events have been observed since about 1950.1 This includes both global events such as Hurricane Yolanda in the Philippines 2013 and local incidents for example flash flooding in Swaledale 2012 or flooding in West Yorkshire August 2014. Every year an estimated 325 million people are now seriously affected by climate change and more than 300,000 people die each year due to related factors and economic losses of US$125 billion are incurred.3 Castleford August 2014 Future Trends The global mean surface temperature change for the period 2016–2035 will likely be in the range of 0.3°C to 0.7°C.4 Most aspects of climate change will persist for many centuries even if emissions of CO2 are stopped. This represents a substantial multi-century climate change effect created by past, present and future emissions of CO2.5 There is a delay of about 30 years for the full impact of carbon emissions to be reflected in global temperatures. Why is keeping below 20C global warming considered essential? Once global temperatures rise to near or above 2oC a greenhouse gas feedback cycle is forecast to be triggered: reduced sunlight reflection from polar ice sheets accelerates heat absorption; warmer oceans hold less CO2 and releases methane hydrates stored on the ocean floor; methane and carbon dioxide released from thawing of Siberian permafrost; and collapse of the Amazon rainforest ecosystem (a carbon store) due to drought 6. Likely Future Climate Change Outcomes Examples for each degree of global warming above 1880 levels 6: 1oC Island atolls such as the Maldives, Tuvalu, Kiribati and the Marshall Islands submerged displacing their populations. 2oC Glaciers in the Cordillera Central, Peru melted away drying up Lima’s fresh water supply. 3oC 80% -100% of Arctic sea ice melted. Amazon rainforest ecosystem collapses due to drought. 4oC Desert areas spreading in Italy, Turkey, Spain and Greece, while Northern Europe experiences increased precipitation. 5oC The UK may experience almost annual severe winter flooding. Precipitation in the Asian monsoon may increase by a third. Severely reduced areas suitable for crop production globally. 6oC Similar conditions were found at the end-Permian era when there were tropical forests at the poles and desert reached 45-60 degrees north. Likely WY&D outcomes: Seasonal changes and increased extreme weather events will particularly affect Yorkshire farmers. Flooding such as the Somerset and Thames valley floods 2014. Rising food and fuel prices affecting the most vulnerable in our community. Increased immigration pressure from environmental refugees. Loss of biodiversity. Substantial costs of climate change passed on through taxation: mitigation and adaptation strategies such as carbon capture, fossil fuel decommissioning, coastal flood defences, and flood repairs. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 IPCC Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis – Summary Report page 3 www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessmentreport/ar5/wg1/WG1AR5_SPM_FINAL.pdf IPCC Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis – Summary Report page 9 “The Anatomy of a Silent Crisis” Human Impact Report Climate Change, Global Humanitarian Forum 2009 page 11. IPCC Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis – Summary Report page 18 IPCC Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis – Summary Report page 25 Six Degrees. Mark Lynas 2007 IPCC Climate Change Report 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change – Summary Report page 10