copyright on city phone holds public

advertisement

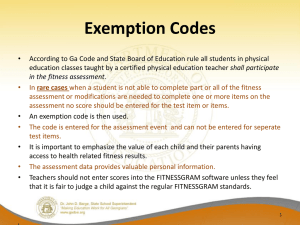

January 31, 2011 Dear City Manager: You have the following question: Is the city required to obtain an ASCAP/BMI license for the playing of a radio station’s material, which includes some music, over the city’s phone system? The phone system has an “on hold” feature that plays music and perhaps other copyrighted material to callers put on hold. The answer is not clear under the present state of copyright law; arguments can be made both ways. I hate to give an answer like that, but this question is a much litigated one with respect to private businesses of various kinds, particularly restaurants and retail stores, but as far as I can determine, it has never arisen where the music is being played on a government’s phone system. However, some of those cases involving private businesses analyze the effect of the “on hold” phone systems had on allegations of copyright violations brought by ASCAP and BMI. Those cases indicate that if the copyright law is held to apply to governments, their “on hold” phone system, assuming copyrighted music or even other material transmitted to outside callers, would trigger copyright violations if the government did not have a license to use such music or material. See Broadcast Music, Inc. v. Claire’s Boutiques, Inc., 949 F.2d 1482 (7th Cir. 1991), Merrill v. County Stores, Inc., 669 F. Supp. 1164 (Dist N..Hampshire 1987). Also see unreported Prophet Music, Inc. v. Shamla Oil Co., Inc. 1992 WL 3002204 (D. Minn.) Section 17 U.S.C.A. ' 110(5), which is part of the copyright law, contains an exemption from that law for certain radio and television transmissions involving copyrighted works. In addition, there is legislative history of that statute. Both appear to indicate the statute was intended to apply to private businesses, but the statute’s language appears broad enough to apply to governments. The exemption in Section 110(5) exempts radio and television transmissions as follows: 5(A) Except as provided in subparagraph (B), communication of a transmission embodying a performance or display of a work by the public reception of the transmission on a single receiving apparatus of a kind commonly used in a private home, unlessB (I) a direct charge is made to see or hear the transmission; or (ii) the transmission thus received is transmitted to the public; Note that Subsection (A) does not contain any exemption for the use of radio transmissions January 31, 2011 Page 2 by governments. The exemption therein is for “a performance or display of a work by the public reception of the transmission on a single receiving apparatus of a kind commonly used in private homes....” That exception itself contains two exceptions: If there is a direct charge made to see or hear the transmission, or the transmission thus received is further transmitted to the public. The cases on the question of whether “on hold” transmissions of copyrighted work sent by a phone system to persons waiting for their calls to be answered is a “further transmission to the public” make it clear that the answer is yes; such audio systems do not reflect a “transmission on a single receiving apparatus of a kind commonly used in private homes.” Standing alone, Section 5(A) could be read to apply to any kind of establishment. Subsection (B) contains another exemption for certain establishments. I am not going to lay out most of it here, because, as I will point out below, it also contains an exception to the exemption that rules out its application to “on hold” audio transmissions. Subsection (B) contains one subset of eating and drinking establishments, and another subset for establishments other than eating and drinking establishments. The subsets are based on size and sophistication of the audio or audiovisual system at issue. Likewise, Subsection (B) does not expressly exclude audio transmissions in government buildings, but the legislative history of Section 110(5), and its mention of eating and drinking establishments and “on hold” establishments might mean private business of other kinds. However, if it is held that Section 110(5) applies to government phone systems that have a “call hold” feature, Subsection (B)(iv) provides that “the transmission or retransmission [must not be ] further transmitted beyond the establishment where it is received.” For that reason, it does not appear to me that a determination need be made of the size of the establishment and what the loudspeaker arrangement is under Subsection (B). The reason is that under Subsection (B)(iv), when the “on hold” system, receives a call, and that system plays music to the callers who are on hold, it almost always transmits or retransmits the call beyond the establishment where it was received, because most such calls will be coming from outside the establishment. But the legislative history of Section 110(5) is important because there are no cases on the question of whether that statute applies to government telephone systems. Notes on the Committee on the Judiciary, House Report No. 94-1476 declare that: With respect to section 110(5) [c] (5) [of this section], the conference substitute conforms to the language in the Senate bill. It is the intent of the conferees that a small commercial establishment of the type involved in Twentieth Century Music Corp. v. Aiken, 442 U.S. 151 (1975) [parallel citations omitted by me.], which merely augmented a home-type receiver and which was not of sufficient size to justify, as a practical matter, a subscription January 31, 2011 Page 3 to a commercial background music service, would be exempt. However, where the public communications was by a means of something other than a home-type receiving apparatus, or where the establishment actually makes a further transmission to the public, the exemption would not apply. The legislative history speaks about the facts in Aiken: On June 17, 1975, the Supreme Court handed down.... [Aiken], that raised fundamental questions about the proper interpretation of section 110(5) of this section. The defendant, owner and operator of a fast-service food shop in downtown Pittsburgh, had “a radio with outlets to four speakers in the ceiling,” which he apparently turned on and left on throughout the business day. Lacking any performing license, he was sued for copyright infringement by two ASCAP members..... [which] finally prevailed by a margin of 7-2 in the Supreme Court.... Under the particular fact situation in the Aiken case, assuming a small commercial establishment, and the use of a home receiver with four ordinary loudspeakers grouped within a relatively narrow circumference from the set, it is intended that the performances would be exempt under clause (5). However, the Committee considered this fact situation to represent the outer limit of the exemption, and believes that the line should be drawn at that point. Thus, the clause would exempt small commercial establishments whose proprietors merely bring into their premises standard radio or television equipment and turn it on for their customers’ enjoyment, but it would impose liability where the proprietor has a commercial “sound system” installed or converts a standard home receiving apparatus (by augmenting it with sophisticated or extensive amplification equipment) into the equivalent of a commercial sound system.... That legislative history appears to be concerned with private businesses, not governments. It is also said in Broadcast Music, Inc. above, which also cited at length the legislative history of the Section 110(5) exemption, that: The legislative history reveals several reasons why Congress passed the § 110(5) exemption. Congress thought it unfair to impose liability on unsuspecting small business persons. Congress January 31, 2011 Page 4 believed also that it was impractical to require small organizations to enter into licensing agreements with performing rights organizations. The secondary use of radio broadcasts in small establishments, Congress also recognized, would have only a minimal effect on authors’ incentives to create new works. [At1489] Likewise, Merrill v. Country Store, above, 669 F.Supp. 1164 (Dist. Hampshire 1988), declares that: Copyright owners alleging infringement must also contend with section 110(5) of that Act, codified at 17 U.S.C. § 1105(5), which exempts certain small business establishments from having to contract with organizations such as ASCAP before publicly playing or rebroadcasting copyrighted musical works.... [At 1168] But the fact that Aiken, and the above cases dealt with the applications of Section 110(5) to business phone systems, is not conclusive on the question of whether that statute applies only to businesses. As I pointed out, neither Section 110(5)(A) nor Section 110(5)(B) expressly exempt governments. In addition Section 110(4) of the copyright law expressly contains exceptions for governments (which are equally unclear, but do expressly apply to governments), in other contexts. It is difficult to understand why the Congress would not have also expressly declared an exemption to Section 110(5) for governments had it intended one. Incidentally, there are exceptions in other contexts for governments’ uses of music and other copyrighted materials under Section 110(4). Those exceptions can also be troublesome, there also being no cases having arisen under that section. It seems to me that, given the relatively inexpensive protection the ASCAP and BMI licensing agreement provides to municipalities, entering into those agreements are, at the present, worthwhile. They afford some mental security to municipal governing bodies’ and staff in that area. If and when cases arise that sort out municipal liabilities under the copyright act under 17 U.S.C.A. § 110, such payments can easily be revisited. As several copyright authorities have pointed out, ASCAP and BMI have very strong records of winning cases under the copyright law. It is generally expensive to be a guinea pig. Let me know if I can help you further in this or any other matter. Sincerely, Sidney D. Hemsley Senior Law Consultant