Case study 11.2: Shale gas

advertisement

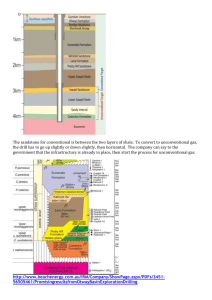

Case study 11.2: Shale gas - to frack or not to frack? The potential commercial exploitation of shale gas has set off an intense debate throughout Europe, the outcome of which will have major repercussions for the three pillars of Europe’s energy policy – the environment; competitiveness and security of supply. Shale gas is natural gas trapped in shale, fine-grained sedimentary rocks, deep underground. Gas is extracted by hydraulic fracturing, commonly referred to as ‘fracking’, which involves drilling long horizontal wells into the shale and pumping large quantities of water, sand and chemicals into the well at high pressure. This creates fissures in the shale which are held open by the sand, allowing the gas to escape to the ground for collection. Opposition to fracking in Europe, where, unlike in the US, shale gas has yet to be commercially exploited on any large scale, is growing and has resulted in moratoriums and even outright bans on fracking in a number of countries (see Table 11.2). Table 11.2: The status of fracking in Europe, 2014 Austria Exploration underway (e.g. OMV in basin near Vienna) but some calls for laws to ban drilling on environmental grounds. Bulgaria 2012 nationwide protests lead to suspension of Chevron’s exploratory shale gas licence. National Assembly passes law banning all forms of fracking. Czech Moratorium on fracking from 2012 to allow time to pass laws to take into Republic account the environmental impact of fracking. Denmark Government views fracking as part of strategy to ease reliance on fossil fuels. Total’s Danish affiliate and state-owned Nordsøfonden have two licences for onshore drilling which started in 2013 France Europe’s second largest shale gas reserves but fracking is banned. In October 2013, French Constitutional Council upholds fracking ban following petition by Schuepbach Energy for restoration of exploration permits revoked following imposition of the ban. Germany February 2013, draft proposals allowing fracking which uses same technology as in US but new coalition government and widespread opposition put fracking on hold for the foreseeable future. July 2014, government proposes seven year ban on fracking at depths shallower then 3,000 metres. Hungary 2009 Exxon Mobil drill first shale gas wells Ireland 2011 options and licences awarded to Energi Oil, Tamboran Resources and Lough Allen Natural Gas Company. 2012 Energy Minister says no fracking to take place in Ireland pending further scientific evidence and advice. Italy Bomba, small southern Italian city refuses a drilling project. Luxembourg 2012 Drilling for shale gas suspended and moratorium imposed. Netherlands Several operators hold licences for exploratory shale gas drilling but government is investigating the environmental impact of shale gas exploration. Meanwhile southern city of Boxtel stops plans for exploratory drilling. Poland Europe’s largest reserves of shale gas and much drilling underway. Shale gas promises the possibility of reducing Poland’s high level of dependency on coal and on Russian gas. Romania Reputedly Europe’s third largest shale gas reserves. Despite nationwide protests, a moratorium on drilling for shale gas lifted in 2013. Government supports fracking on grounds of energy independence and lower prices but anti-fracking demonstrations continue. Spain 2013 northern region of Cantabria bans fracking on environmental grounds – goes against national government’s aspiration for jobs in a region rich in shale gas. Sweden Exploratory drilling underway. UK Some drilling but no commercial production underway. 2011 Cuadrilla suspends drilling near Blackpool after two small earthquakes reported. 2012 drilling re-started subject to stricter monitoring. 2012 Northern Ireland Assembly calls for moratorium on fracking pending environmental assessment but moratorium not enacted by the minister. The main objections to fracking are based on claims about potential environmental damage. Several of these claims are contested but, inevitably, given the relative newness of large-scale fracking, the exact environmental impact is unclear, leading some European countries to impose a moratorium on fracking until its environmental implications are more firmly established. The main environmental concerns surrounding fracking are: - water pollution from contamination with methane or drilling chemicals. This threat has been confirmed by the US Environmental Protection Agency and a UK Select Committee which also maintain that this pollution is no greater than that from conventional gas extraction techniques and can be mitigated by best practice; - accidental release of hydraulic fracturing fluid (possibly containing hazardous chemicals) resulting from spills, leaks and faulty well construction; - the amount of wastewater containing contaminants; - the huge amounts of water and chemicals needed and which may disrupt water supplies for other uses; - potential damage to wildlife habitats; - the possible emission of climate warming and explosive methane; - tremors; - a continuing reliance on fossils fuels contrary to climate change objectives; - a diversion of effort away from the development of renewable and less carbon-intensive resources. On a more positive note, supporters of fracking argue that it reduces the need for consumption of coal, the most carbon emitting of all fossil fuels and will facilitate the transition to a less carbon-intensive environment. In the process, the development of this new energy source will help keep energy prices down and improve Europe’s energy security situation by reducing the need for imported gas. Although not without its opponents and with fracking bans in place in several locations, commercial exploitation of shale gas in the US is the most advanced in the world. Since 2005, when US gas production was at a long term low, total US gas production has increased by over one third and the US has overtaken Russia as the world’s largest gas producer (Russia’s proven gas reserves, however, are over three times greater than those of the US). This boost to US gas output has transformed the US energy supply situation by massively reducing its reliance on gas imports, freeing up coal for export and reducing energy prices. In 2013 helped by an increase in renewable energy production as well as by gas shale, US dependence on primary energy imports had fallen to 13 per cent in 2013 from 30 per cent in 2005 whereas EU energy import dependency reached 53 per cent in 2013. This improvement in US energy independence and related fall in US energy prices has been a mixed blessing for European business. On the one hand, reduced US participation on world energy markets contributed to the fall in energy prices in 2014. The US consumes most of its gas production but, if current trends continue, it may start to export more gas. At the very least, increased domestic gas production has freed up more US coal for export, particularly to the Netherlands, Italy and Germany. In turn this has reduced the relative price of coal in Europe with negative impacts on carbon dioxide emissions. On the other hand, the surge of US shale gas output and related fall in US energy prices has raised questions about EU industrial competitiveness. According to statistics from the International Energy Agency, between 2005 and 2012, gas prices to industry increased by 35 per cent in the EU compared to a fall of 66 per cent in the US. Industrial electricity prices were also affected, rising 38 per cent in Europe and falling four per cent in the US over the same period. The impact of these differential price changes clearly has the greatest impact on Europe’s most energy intensive sectors but they have resulted in calls for less strict carbon policies in Europe and strengthened the position of the shale gas lobby. Assuming the environmental concerns about shale gas production are overcome in Europe ( a development which is far from assured), it is still too early to forecast the full potential impact of large-scale commercial production as estimates of total, recoverable shale gas reserves not only in Europe but also in the US and elsewhere in the world are highly contested and constantly revised. However, even the most conservative estimates imply significant increases to natural gas reserves in Europe, albeit at a much lower level than in the US. Moreover, European shale gas reserves are more dispersed than in the US where over one third of its reserves are in the huge Marcellus Basin with the rest in other large fields. European reserves are more scattered with the greatest concentration in France and Poland, indicating potentially lower economies of scale in their exploitation. The ultimate fate of fracking in Europe will depend on the decisions of individual member states as decisions about energy mix are outside the competence of the European Union – a factor which undermined Gazprom’s lobbying for a Europe-wide ban on fracking. However, the EU can influence national decisions through the environmental objectives it sets. Overall, the jury remains out on the desirability of gas fracking in Europe from an environmental point of view, notwithstanding the potential for fracking to improve Europe’s supply security. Whatever the merits of the case for and against fracking, there is a wider consensus that scientific evidence is not yet sufficiently robust to support the case of either side. CONCLUSION Energy is crucial to Europe’s future and the three main pillars of European energy policy – competitiveness, sustainability and energy security– run through all aspects of EU energy activity. Each pillar is itself made up of many individual initiatives to contribute to achieving overall energy policy objectives and it is clear that the pillars are closely integrated and, ideally, work in concert with each other. As the above section on energy security demonstrates, energy security depends on a variety of actions, including reducing demand through increased energy efficiency and energy demand through greater use of renewable which also serves the environmental pillar. Case questions 1. What is the potential impact of the development of shale gas production in Europe on the three pillars of European energy policy? 2. What is the potential impact of shale gas production on European business in the following scenarios (in both cases, consider the impact both on energy producers and on energy business consumers): a. If the US and the rest of the world develop shale gas and Europe does not; b. If the EU develops shale gas. 3. How does the shale gas controversy fit in with the principles of EU environmental policy outlined in Chapter Twelve.