Hailemichael Demissie - University of Warwick

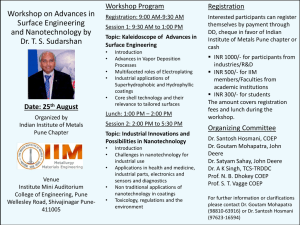

advertisement