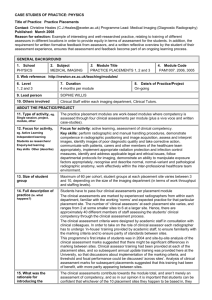

Academic Year Structure & Assessment Group

advertisement

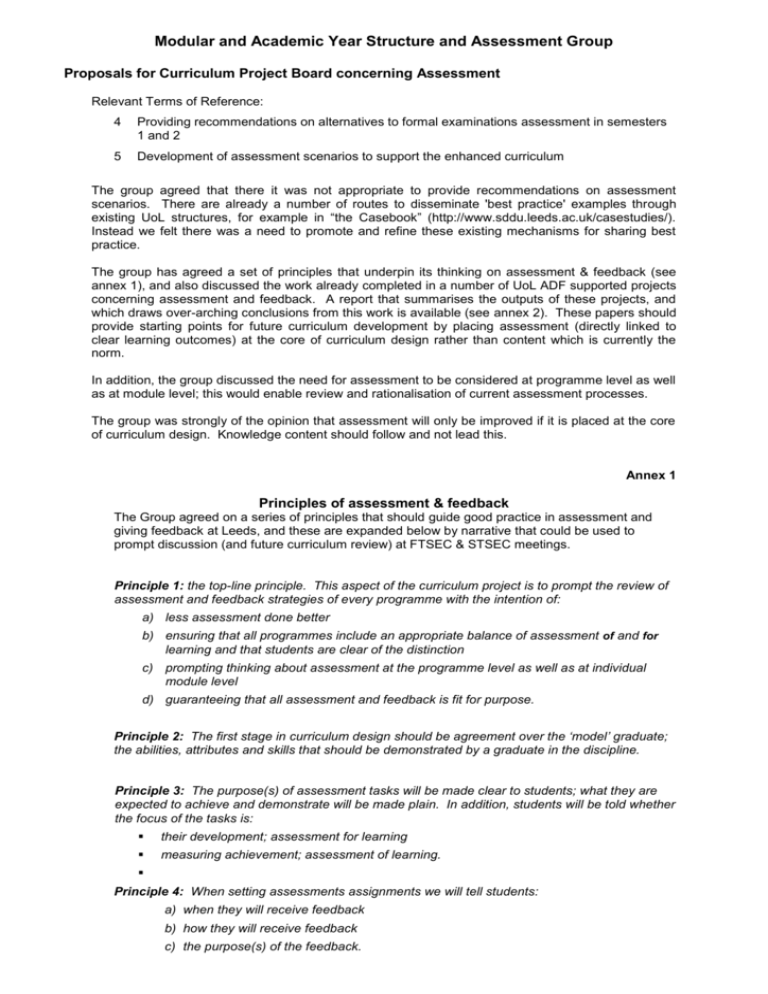

Modular and Academic Year Structure and Assessment Group Proposals for Curriculum Project Board concerning Assessment Relevant Terms of Reference: 4 Providing recommendations on alternatives to formal examinations assessment in semesters 1 and 2 5 Development of assessment scenarios to support the enhanced curriculum The group agreed that there it was not appropriate to provide recommendations on assessment scenarios. There are already a number of routes to disseminate 'best practice' examples through existing UoL structures, for example in “the Casebook” (http://www.sddu.leeds.ac.uk/casestudies/). Instead we felt there was a need to promote and refine these existing mechanisms for sharing best practice. The group has agreed a set of principles that underpin its thinking on assessment & feedback (see annex 1), and also discussed the work already completed in a number of UoL ADF supported projects concerning assessment and feedback. A report that summarises the outputs of these projects, and which draws over-arching conclusions from this work is available (see annex 2). These papers should provide starting points for future curriculum development by placing assessment (directly linked to clear learning outcomes) at the core of curriculum design rather than content which is currently the norm. In addition, the group discussed the need for assessment to be considered at programme level as well as at module level; this would enable review and rationalisation of current assessment processes. The group was strongly of the opinion that assessment will only be improved if it is placed at the core of curriculum design. Knowledge content should follow and not lead this. Annex 1 Principles of assessment & feedback The Group agreed on a series of principles that should guide good practice in assessment and giving feedback at Leeds, and these are expanded below by narrative that could be used to prompt discussion (and future curriculum review) at FTSEC & STSEC meetings. Principle 1: the top-line principle. This aspect of the curriculum project is to prompt the review of assessment and feedback strategies of every programme with the intention of: a) less assessment done better b) ensuring that all programmes include an appropriate balance of assessment of and for learning and that students are clear of the distinction c) prompting thinking about assessment at the programme level as well as at individual module level d) guaranteeing that all assessment and feedback is fit for purpose. Principle 2: The first stage in curriculum design should be agreement over the ‘model’ graduate; the abilities, attributes and skills that should be demonstrated by a graduate in the discipline. Principle 3: The purpose(s) of assessment tasks will be made clear to students; what they are expected to achieve and demonstrate will be made plain. In addition, students will be told whether the focus of the tasks is: their development; assessment for learning measuring achievement; assessment of learning. Principle 4: When setting assessments assignments we will tell students: a) when they will receive feedback b) how they will receive feedback c) the purpose(s) of the feedback. Principle 5: When feedback is provided it will be specific and designed to inform students about both what they have done well and how they can improve. This will require that feedback is given on the work as well as on cover / summary sheets. Principle 6: We will need to discuss our revised processes for giving feedback to students with our external examiners; currently some feedback on summative work is provided to justify the grade to peers rather than give detailed feedback to the learner. Principle 7: We will ensure that processes are in place so that feedback to students is individual, timely and fit for purpose. This should enable students, with support if needed, to set academic targets for themselves. Principle 8: A map should be available for each programme that: a) shows how the learning outcomes are linked to the assessment methods both at module and programme level b) demonstrates how assessment is mapped across the programme as well as within modules c) illustrates progression / value added across levels of the programme. Narrative for discussion at FTSEC & STSEC meetings: Curriculum design The first stage in curriculum design should be agreement over the ‘model’ graduate; the abilities, attributes and skills that should be demonstrated by a graduate in the discipline. At Leeds we had a clear statement of these based on the University values and additional guidance is available in subject benchmark statements. How we assess should flow from these intended outcomes, as should the teaching approaches we use and the content we include; the basis of constructive alignment. Setting assessment / assignments more guidance should be given by staff to students about the expectations of the assessment; perceptions between staff and students of what assessments require and expect vary (as demonstrated by the MARK project) and clarity is essential Feedback the majority of feedback should be provided to students in advance of the final submission of the assignment / assessment feedback should be about the work in order to assist the student to improve feedback needs to be written on the work as well as on a cover / summary sheet we are teaching students as individuals within groups - one way to make feedback more individual is to have the feedback on work [and the annotated scripts] available to personal tutors we should be linking feedback effectively to LeedsforLife [and possibly any future HEAR] we could move towards target setting based on feedback / LeedsforLife as a means to direct students more Mapping we should map assignments to the outcomes / skills of modules more effectively the lack of mapping of assessment across programmes is a weakness in our processes we need to review the roles and responsibilities of the module and programme leaders it is possible that the options within a programme enable students to ‘escape’ essential demands of the Leeds Graduate skills set; we should resolve this when we require maps of assessment [and, perhaps, feedback] we need to put processes in place both to monitor and assure the maps Work load It was questioned which was broken: o getting the grades correct ? o getting feedback sorted ? o both ? As a result we need to decide where to focus our efforts within the limited time available. It was recognised that these approaches could add to the demand / workload on staff. However, it was felt that the status quo was not acceptable and that changes need to be made, and this will have to be recognised in workload models. Annex 2 Assessment and feedback at the University of Leeds looks like.... 1. This paper outlines findings from one JISC-funded and three University-funded assessment and feedback projects, and describes an ideal model for assessment and feedback at the University of Leeds. It represents an attempt to capture best practice based on the research evidence and is an opportunity for the University to use some of its own funded work to enhance and evidence its practice. 2. The projects involved are: a) The ADF-funded Assessment and Feedback project in Engineering (Anthea Connolly, Martyn Clark, Simon Biggs) and the SEE UTF (Graham McLeod, Rob Mortimer) project. These projects examined the available primary and secondary research evidence to influence change within their disciplines. b) The ADF-funded MARK project (Mitch Waterman and Siobhan Hugh-Jones) which is an original piece of primary research carried out using a verbal protocol methodology to capture what assessors are noticing when they mark student work. c) The JISC-funded Leeds Building Capacity project (Chris Butcher, Karen Llewellyn) which considered good practice in using technology to provide feedback to students, and established 10 pilot projects at Leeds. 3. The important contributions of the Leeds University Code of Practice on Assessment, the Partnership, and the Leeds University Union Principles of Good Feedback are acknowledged. 4. It is recommended that the paper be considered by the Structure of the Academic Year and Assessment Working Group (Curriculum Enhancement Project) and that this group responds with suggestions for how the paper could be used across the institution. A Our assessment 1. Assessment is not merely used for measuring and certifying student learning; assessment tasks support students towards the achievement of learning outcomes (assessment of learning and assessment for learning). 2. Assessment is placed at the centre of the curriculum and, along with learning outcomes, is given consideration at the point when a course of learning is being developed. 3. The overall assessment approach is a programme-wide approach. Assessment tasks are not construed as discrete events. 4. Assessments test achievement of module level learning outcomes which feed directly into programme LOs. 5. LOs are disaggregated by year and build over the course of a programme. 6. LOs are written so that they cover four areas: knowledge, application of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. 7. We recognise that assessment tasks can test specific aspects of these four areas, and therefore that we need to use a variety of assessment methods. 8. All assessment tasks provide evidence that a learning outcome has/has not been reached. 9. Assessment criteria differentiate levels of achievement of learning outcome(s) and hence grades. 10. Assessment criteria are specific to the assessment task. 11. Learning outcomes must be achieved for progression or award. Achievement is indicated by a pass and the alternative is a fail. 12. Assessment tasks and the feedback on assessment tasks in conjunction with marking criteria help students to make judgments about their own work and the work of others. 13. In vocationally focused subjects assessment has a strong practical (learning by doing) component. 14. Formative assessment is recognised as a valuable learning aid in particular because it: provides regular opportunities for feedback on work; helps students to understand how they are performing and, if feedback is effective, gain some sense of how to improve; provides practice for the summative assessment(s). B Our assessors 1. Assessors are trained and skilled in the practice of assessing work. 2. Novice markers are inducted into best practice in assessment at a local level with substantial episodes of moderation and second marking experiences. 3. Subject experts typically provide more useful feedback and their grades are more likely to be informed by content rather than presentation, and so, where possible, subject experts mark in their own field only. 4. Staff are aware that assessment cultures exist at a discipline level and that these may foster the retention of a received wisdom about assessment practice and standards. These can be difficult to identify and challenge internally, and therefore external review helps to challenge aspects which have become ingrained but are not necessarily helpful. 5. Assessors are attentive to the potential influence of their own personal model of how to complete a piece of work (e.g. that an introduction should look a certain way) when this is not specified in the task or the marking criteria. Being aware of this promotes the transparency of the assessment process. 6. Sufficient time is allocated to the delivery of good assessment and feedback in workload models. C How we measure achievement 1. Assessment criteria are used to measure how well a student has achieved the learning outcomes and met the demands of the assessment task. 2. Assessors mark for features explicitly defined in the marking criteria and task demands. 3. Presentation and content features that will attract marks are clearly defined in either generic marking criteria or specific task demands. If they are not, assessors should not mark for them. 4. Assessors are cautious about making inferences about students, which further influences the grade awarded, but about which they cannot be certain e.g. the level of effort the student has put into a piece of work or their assumed position in the class. 5. Assessors are cautious about allowing a minor element of the work (e.g. one brilliant sentence) to overly influence the grade awarded. This caution secures a clearer relationship between the entirety of feedback and the grade awarded. 6. Assessors guard against generating a (typically positive) final review of the work that is inconsistent with (typically less positive) judgements of specific features of the work. 7. Assessors review their script-based feedback prior to the awarding of a mark and the generation of coversheet feedback. This promotes coherency and transparency between feedback and grades. D How our students understand the assessment process 1. Students can see how assessment tasks relate directly to the intended learning outcome(s), and hence their relevance to a course of learning. 2. In vocationally-focused courses assessment activities relate closely to a student’s motivations in choosing their subject and therefore real world problems, practical experiments, case studies and projects are prominent in the curriculum. 3. Students are primed for the assessment process at induction and even before that at recruitment; we deliver the key messages about the learning process at Leeds in our marketing materials. 4. Students understand that assessment tasks help them to make judgments about their work and that of others. 5. We help students to understand marking criteria, how assessors use them and how students can utilise marking criteria as they complete assessment tasks. We are aware that even if we give students marking criteria, they may be written in academic language which needs to be ‘translated’ for the benefit of students. Marking criteria and task demands should reflect a shared understanding between students and staff which typically will require dialogue between students and staff. 6. The student’s personal tutor has an overview of the totality of work that a student submits and of its strengths and/or areas for development. E Feedback 1. Feedback on work is a cornerstone of student learning; students use feedback to help better understand their work and learning, and to improve the quality of their future work and the way they learn. 2. Students are supported in understanding the meaning of feedback and how to use it. This helps them to be engaged with the feedback on their work. 3. Students receive feedback on work regularly and whilst the work is still fresh in their minds. 4. Students know who has marked their work and how to contact them to follow up on feedback related queries. 5. Appropriate technology is used in order to extend the ways in which feedback is provided and reduce the time delay in providing feedback to the benefit of the learners. F What feedback works? 1. Specific, informative feedback makes clear where strengths/ weaknesses lie and where the student demonstrates inaccuracies or a lack of understanding. 2. Feedback avoids ambiguous ticks or comments such as ‘good’; feedback specifies what the student has done well. 3. Students do not expect praise for work that is not good but they do expect clear feedback on what they need to do to improve. 4. As compared to coversheet feedback, script-based feedback more clearly indicates to students which aspects are influencing the grade awarded, and we recognise that students can find it hard to interpret feedback and grades that are provided in coversheet format only. 5. Coversheet feedback often differs in tone and specificity from script-based feedback and it can be difficult for students to understand how to reconcile apparently conflicting comments on coversheets. 6. It is not always possible for assessors to return to students their annotated scripts. Therefore we ensure when we give coversheet feedback for written work that: it is tailored to the assessment; contains the learning outcomes relevant to the assessment; contains the clearly stated marking criteria; performance is indicated in relation to the marking criteria; and contains personalised comments about the work. 7. Students are often more attentive to feedback annotated on their work than to feedback written on a coversheet. Students also value other forms of feedback, including individual verbal face to face or audio/video feedback. 8. If we cannot deliver individual feedback whilst work is still fresh in students’ minds, we can help them to continue thinking about their work and to stay in the ‘learning loop’ through group feedback, either face to face, or via audio/video. 9. Multiple assessors involved in module assessment should offer feedback in a consistent form to all students. 10. Staff and students can work in partnership to identify the most appropriate forms of feedback for a given assessment. 11. Whilst timeliness of feedback is important (and staff should adhere to the University 3 week turnaround rule whenever possible), effective feedback is even more important. Students prefer effective feedback that can have a material impact on subsequent submissions over timely but less useful feedback. G How our students engage with feedback 1. Students are interested to know how they have performed on a piece of work (relative to their own standards and to others). 2. Students engage with the feedback that they receive on their work; they want to know the strengths and weaknesses of their work, and how to improve. We understand that students’ priorities in relation to feedback may not be the same as the assessor’s priorities in feedback. 3. Students are alert to where opportunities for feedback lie: they are aware of when they receive feedback; they know how to get the most from the feedback they receive; and they ask for help/more feedback when they need it. Drafted by Anthea Connolly, Chris Butcher, Mitch Waterman, Siobhan Hugh-Jones, Robert Mortimer & Graham McLeod version 7 - March 2012