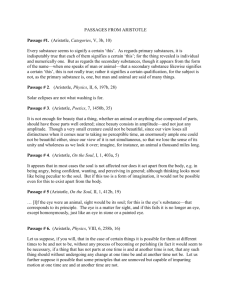

Aristotle Psychology

advertisement