Sentence Structure Guidelines for Effective Writing

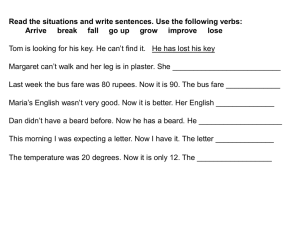

advertisement

Some Guidelines for Choice of Sentence Structures 1. A short, simple sentence adds emphasis. Try using a short, clear sentence to get your main idea across. (This only works if the rest of your sentences are compound or complex.) This effect is intensified with the rhetorical use of fragments to add emphasis. A technique often used in advertising. 2. Avoid accidental use of a series of short, simple sentences or compound sentences strung together with "ands"; such structures tend to sound simple-minded, as though written by a child: "We got paper hats and we pinned the tail on the donkey and we had chocolate ice cream and Randy sat on a piece of cake and I won a prize." Use a series of short sentences consciously to give a well-paced sense of cause and effect. 3. A long sentence allows for deliberation, qualification, and explanation, usually slowing the forward movement of thought. Use long sentences in the middle of paragraphs to elaborate on main ideas. 4. Use subordination carefully to mark out your main ideas. The most important idea should be in the independent clause; the secondary ideas should be relegated to subordinate clauses: "After we got paper hats and ate chocolate ice cream, after Randy sat on a piece of cake and everyone pinned the tail on the donkey, I won a prize." 5. A sentence punctuated with interruptions or asides creates a casual, colloquial effect and makes the reader feel s/he is participating in the writer's thought processes:"Twice in my life, for reasons that escape me now, though I'm sure they were discreditable, I allowed myself to be persuaded that I ought to take a hand in turning out a musical comedy.". 6. The two places where emphasis naturally falls in the sentence (as in the paragraph and essay) are at the beginning and at the end. The short, simple sentence takes advantage of emphasis with the subject at the beginning; using inversions or writing a periodic or cumulative sentence focuses interest at the end: "The house itself she hated, but the yard was grand." "Nature I loved; and next to nature, art." "Beverly, who had so often thought of herself only as a housewife, decided to run for president." 7. A balanced sentence highlights a balanced thought by its structure. Probably the single, most important technique for making writing more effective at the sentence level is parallelism. Use parallel structures whenever you have clauses or phrases linked by co-ordinators such as semi-colons and "ands": The novel concentrates on character; the film intensifies the violence. The Government tries to get the most out of taxes; the individual tries to get out of the most taxes. The dictator exploited his country's resources, stole from the common people, executed those who opposed him, and trampled over their corpses. Next morning when the first light came into the sky and the sparrows stirred in the tress, when the cows rattled their chains and the rooster crowed and the early automobiles went whispering along the road, Wilbur awoke and looked for Charlotte. Notice how these sentence structure strategies are used in the following passage by Virginia Woolf: But while we amuse ourselves with this brilliant nobleman and his views on life we are aware, and the letters owe much of their fascination to this consciousness, of a dumb, yet substantial figure on the other side of the page. [Aside that draws us in and asks us to share thinking porcess.] Philip Stanhope is always there. [Good example of using a short, simple sentence to get attention.] It is true that he says nothing, but we feel his presence in Dresden, in Berlin, in Paris, opening the letters and pouring over them and looking dolefully at the thick packets which have been accumulating year after year since he was a child of seven. parallelism He had grown into a rather serious, rather stout, rather short young man. Uses short sentences to emphasize how short and intellectually limited he is. He had a taste for foreign politics. A little serious reading was rather to his liking. And by every post the letters came -- urbane, polished, brilliant, imploring and commanding him to learn to dance, to learn to carve, to consider the management of his legs, and to seduce a lady of fashion. Uncle's letters again describe in long sentence full of parallelism. He did his best. Sharp cpntrast of simple sentence; again suggests limits. He worked very hard in the school of the Graces, but their service was too exacting. He sat down halfway up the steep stairs which lead to the glittering hall with all the mirrors. He could not do it. He failed in the House of Commons; he subsided into some small post in Ratisbon; he died untimely. He left it to his widow to break the news which he had lacked the heart or courage to tell his father -- that he had been married all these years to a lady of low birth, who had borne him children. The Earl took the blow like a gentleman. His letter to his daughter-in-law is a model of urbanity. He began the education of his grandsons. . . ." Notice how elaborate parallelism is the hallmark of the most formal and most emotionally moving ceremonial speeches in our country's history: When we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! Free at last! Thank God almighty, we are free at last!" ---Martin Luther King, Jr. Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans -- born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud in our ancient heritage -- and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today, at home and around the world. Now the trumpet summons us again -- not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need -- not as a call to battle, though embattled we are -- but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle, year in and year out, "rejoicing in hope, patient in tribulation" -- a struggle against the common enemies of man: Tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself. ---John F. Kennedy