Daoism: The Unspoken Way

advertisement

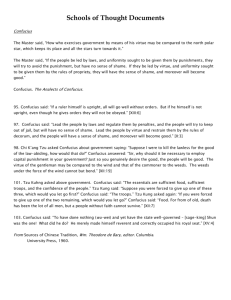

Legalism Legalism was the third major Chinese philosophy. Among its chief supporters was Han Fei Tzu (HAHN FAY DZOO) who died in 233 BCE. Han Fei Tzu insisted that the only way to achieve order was to pass strict laws and impose harsh punishments. Unlike Confucius, Han Fei Tzu was not interested in ethical conduct. He also opposed the Daoist emphasis on meditation. He felt that the way to create a stable society was through efficient government. And he believed that the ruler should have absolute power to make the system work. Because of their emphasis on law, Han Fei Tzu’s teachings became known as Legalism. To Legalists, strength, not goodness, was a ruler’s greatest virtue. “The ruler alone possesses power,” declared Han Fei Tzu, “wielding it like lightning or like thunder.” Legalism was an authoritarian philosophy—that is, it taught unquestioning obedience to authority. Han Fei Tzu said that people were easily swayed by greed or fear. Only the ruler knew how to look after their best interest. Therefore, the ruler should make laws as needed, enforcing them with rich rewards for obedience and severe punishment for disobedience. To the legalists, rule by law was far superior to the Confucian idea of rule by good example. Legalists had such a low opinion of human nature that they did not believe people were capable of loyalty, honesty or trust. Only the threat of harsh punishment, they argued, would ensure order and stability in society. In the following excerpt, Han Fei Tzu explains why he thinks his system is superior. “When the wise man rules the state, he does not count on people doing good of themselves, but employs such measures as will keep them from doing any evil. If he counts on people doing good of themselves, there will not be enough such people to be numbered by the tens in the whole country. But if he employs such measures as will keep them from doing evil, then the entire state can be brought up to a uniform standard. The ruler does not busy himself with morals, but with laws. Those who are ignorant about government insistently say: ‘Win the hearts of the people’ … As if all that the ruler would need to do would be just to listen to the people. Actually, the intelligence of people is not to be relied upon any more than the mind of a baby…the baby does not understand that suffering a small pain is the way to obtain a great benefit… The ruler regulates penalties and increases punishments for the purpose of repressing the wicket, but the people think the ruler is severe… This is the method of attaining order and maintaining peace, but the people are too ignorant to appreciate it.” Confucianism Westerners know Kongzi (KOOHNG-ZUH), meaning, “Kong the Philosopher,” or “Reverend Master Kong,” as Confucius. At age 22, Confucius began teaching, and soon gained many followers. In time his ideas and teachings, as written by his followers in a collection of writings called Analects, became known as Confucianism. Confucius was not a religious prophet and had little to say about the gods, the meaning of death, or the idea of life after death. Instead, he taught about the importance of the family, respect for one’s elders, and reverence for the past and one’s ancestors. These three concepts formed the basis of Confucian philosophy. Confucius taught that harmony resulted when people accepted their pace in society. He stressed five key relationships: father to son, elder brother to younger brother, husband to wife, ruler to subject, friend to friend. Confucius believed that, except for friendship, none of these relationships was equal. For example, older people were superior to younger ones and men were superior to women. According to Confucius, everyone had duties and responsibilities. Superiors should care for their inferiors and set a good example, while inferiors owed loyalty and obedience to their superiors. A woman’s duty was to ensure the stability of the family and promote harmony in the home. Correct behavior, Confucius believed, would bring order and stability. Confucius had a primary interest in politics and wanted to end the political disorder of his time. He believed this could be accomplished in two ways. First, every person should accept an assigned role in society and perform the duties of that role. Second, government should be virtuous. Instead of relying on military power, rulers should be honest and have concern for others. Only well-educated and extremely virtuous officials should be appointed to run the government. Confucius taught that government should set a good example, believing that the people would willingly obey a ruler who lived and governed virtuously. Virtue, in Confucian teaching, consists of correct behavior toward others. This basic principle resembled the Christian Gold Rule, although stated negatively: “What you do not like when done unto yourself, do not do unto others.” Confucius also felt that a ruler could achieve more by setting a good example than by passing laws. Whereas Daoism advocated a passive life for individuals and urged the least possible government, Confucius urged individuals to participate forcefully in society and recommended vigorous government action. He further believed that a ruler who practiced the Confucian virtues would govern as an influential, parental force. Unlike other philosophies, Confucianism placed little emphasis on the hereafter. Over the centuries, Confucian ideals shaped Chinese society. Chinese law was based on Confucian principles, and the idea of respect for elders dominated family life. Emperors had temples honoring Confucius built in every province. Confucian scholars became the main force in government. Every candidate for government office had to memorize the Five Classics and the Four Books, which contained the teachings of Confucius and his followers. Daoism: The Unspoken Way Daoism got its name from its central idea, Dao, which can be defined as the “Way of Nature.” Laozi saw Dao as an indescribable force that governed the universe and all nature. At about the same time as Confucius, during the late Zhou period, a man called Laozi (LOWDZUH), or “Old Master,” taught ideas that in some ways seem the opposite of Confucianism. He rejected formal social structures and the idea that people must fill specific roles in society. Also in contrast to Confucius, Laozi shunned public life, leaving anything we know of him heavily mixed with legend. Daoists believed people should renounce wealth, power and ambition. They also rejected social structures, and formal codes of behavior. Daosits believed people should attune themselves to nature and the Dao, which is the eternal force that permeates everything in nature. Daoists opposed conflict and strife. They wanted to end conflict between human desires and the simple ways of nature. By emphasizing harmony with nature and its underlying spirit, Daoists profoundly influenced Chinese arts, particularly painting and poetry. Their influence lingers in painting, poetry, and other arts to this day. Daoists viewed government as unnatural and, therefore, the cause of many problems. “If the people are difficult to govern,” Laozi declared, “it is because those in authority are too fond of action.” To Daoists, the best government was one that governed the least. Governments should minimize their controls over the people. Since laws cannot improve conditions, people should be permitted to conduct their own affairs. “The more laws and edicts are imposed,” began one Daoist saying, “the more thieves and bandits there will be.” Daoist simplicity seems to oppose Confucianism formalism. Confucianism provided the pattern for government and one’s place in the social order, and Daoism, emphasized harmony within the individual attuned to nature. A Chinese theory related to Daoist ideas was the concept of yin and yang, the two opposing forces believed to be present in all nature. Yin was cool, dark, female, and submissive, while yang was warm, light, male and aggressive. Everything had both elements. For harmony the two elements had be in balance. Human life and natural events, including the changing seasons, resulted from the interplay between yin and yang. The concept of yin and yang helped the Chinese reconcile seeming opposites—like Dao simplicity and Confucian formalism. In closing, Daoist teachings forced chiefly on the individual, but they also included views on society and government. The Daoists strongly opposed the existence of a large powerful government with a bureaucracy and many laws. Their vision of an ideal society was carefully explained in the following manner: Let there be a small country with a few inhabitants. Though there be labor-saving devices, the people would not use them. Let the people mind the death and not migrate far. Though there be boats and carriages, there would be no more occasion to ride in them. Though there be armor and weapons, there would be no occasion to display them.