Literature Review – Jake Maria

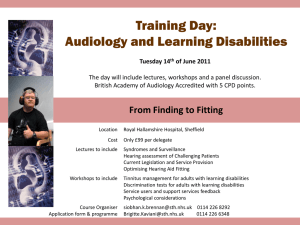

advertisement

Running head: EDUCATING STUDENTS WITH THE IDEA Educating Students with the IDEA Jake Maria Seattle Pacific University 1 EDUCATING STUDENTS WITH THE IDEA 2 Educating Students with the IDEA The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was originally enacted by congress in 1975 under the administration of President Ford. Since that time there have been numerous revisions and amendments with the intent to ensure that children with disabilities are able to receive free public education. One of the main goals for IDEA is to legislate special education laws so that schools and governments are clear on expectations for students with special needs. One of the main components of special education and of IDEA is the Individualized Education Plans (IEP’s) that help students with disabilities meet their specific educational goals and needs so that they can graduate. The IEP is used as the tool for demonstrating the effectiveness of specially designed instruction. Yell and Shriner (1997) state that performance goals are essential to the education of all students, especially those with disabilities. In 1990 President George H.W. Bush signed amendments to IDEA and IEP’s became an integral part of the education of students with disabilities. Students are guaranteed by law this educational plan as well as instructional implementation that are free, equitable and accessible. “FAPE (Free and Appropriate Education) provides mainstream education for identified students ages 3-21 in the least restrictive learning environment (LRE). Students identified with disabilities are provided with an IEP (Individual Education Plan) using diagnostic assessments and intervention feedback to construct specially designed instruction for their academic and behavioral success” (Zirkel, 2011). Since the beginning of IDEA all U.S. states have accepted federal funding and are subject to the regulations. The most recent significant revision in 2004 helped define the purpose of the IDEA to help special education students become prepared for further education, employment and independent living. The laws through EDUCATING STUDENTS WITH THE IDEA 3 IDEA work accordingly with Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the American Disiabilites Act of 1990 to insure equitable services to students with disabilities. Yell and Shriner (1997) summarize in the Focus on Exceptional Children the 1997 Amendments of the Individuals with Disabilities Act and how the changes will affect students, teachers and administrators. This article proves its relevance to special education by highlighting the program processes as well as the discipline of students with disabilities and the staff and faculty accountability. Yell and Walker (2010) explain how The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA) of 2004 makes significant and controversial changes to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). “Two very significant changes in this law are provisions that (a) allow school districts to spend up to 15% of their IDEA Part B funds on early intervening services in general education settings and (b) prohibit states from requiring that school districts use discrepancy formulas to determine if students are eligible for special education services in the category of learning disabilities” (Yell and Walker, 2010). Congress also recommended that school districts use a response to intervention (RTI) procedure in both early intervening services (EIS) and for the identification of students with learning disabilities. The use of assessment with students with disabilities helps ensure accountability by the teachers as well as the school and the district that they are properly upholding their duties in regards to the Individuals with Disabilities Act. Response to Intervention (RTI) or Early Intervening Services (EIS) are also ways to assess the level of learning and progress of students with disabilities. Functional behavior assessments along with RTI and EIS help decide how well students are able to read, write and do math and science when compared with their expected level. RTI is required for students who have specific learning disabilities (SLD) in order to help them progress through their education (Zirkel 2011). EDUCATING STUDENTS WITH THE IDEA 4 According to Zirkel (2010) students with specific learning disability (SLD) continue to account for a higher proportion of all special education enrollments than any other classification under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Probably the most frequent topic in the special education literature since the 2004 amendments to IDEA has been the movement toward a response-to-intervention (RTI) approach for identifying students with SLD. Currently the majority of states permit both RTI and severe discrepancy–with approximately 20 states additionally allowing the third research-based option–thereby effectively leaving the choice to local districts. (Zirkel, 2010) In 1982 the United States Supreme Court handed down its first major decision regarding IDEA. In Board of Education of the Hendrick Hudson Central School District v. Rowley, the U.S. Supreme Court interpreted the IDEA requirement that schools provide a “free and appropriate public education” (FAPE) to students with disabilities to mean that schools should provide services necessary for children “to benefit” from instruction. However, the Court limited the FAPE standard, stating that “the intent of the Act was more to open the door of public education … than to guarantee any particular level of education once inside.” (Crockett and Yell, 2008) The meaning of FAPE has not only continued to evolve, violations have also increased thus incrementing the number of families and school districts that move towards litigations. The policies we have now in the U.S. as well as the complexities of accountability require educators to be more diligent, and parents to be more vigilant in using data-based instructional practices. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), parents and families of children with disabilities play a key role in enforcing the law. They initiate litigation and raise issues that otherwise may not gain attention. In order to pursue these issues, parents must find attorneys who are knowledgeable about IDEA and willing to accept cases where fee payment may be EDUCATING STUDENTS WITH THE IDEA 5 deferred or delayed until the case is settled. This process can be long and tedious and many parents may see this as not worth the time or risk for the education of their child. Families and parents of children with disabilities have had a very difficult process of resolving any disputes with school districts. IEP’s or other matters with the education of the student need to be resolved with schools and Local Educational Agencies (LEAs) through a provided process of mediation. The Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) has spawned much litigation in which parents of children with disabilities and school districts disagree over the content of a student’s special education program. Supreme Court rulings are of tremendous importance, because they establish the legal standard for, and must be followed throughout, the entire country (Yell et al, 2009). In the 30 years since the passage of the IDEA, from 1975 to 2005, the Supreme Court heard only seven cases that directly involved students with disabilities and the IDEA. In the period from 2005 to 2007, the Supreme Court heard four cases on special education and issued rulings in three of these cases (Yell et al, 2009). This increase represents a significant change in the special education cases heard by the high court. The Supreme Court rulings are of great importance to students with disabilities, their parents, and school districts, however it seems that as we progress and more laws and amendments are made to IDEA we will increase the number of legal cases involved with IDEA. The procedural rights of parents is the key issue that seems to be getting more attention and perhaps hurting what IDEA was intended to do. In the future years if the education for students with disabilities is to continue to grow, then their needs to be a review of the legal issues that have been challenging it. The implications of these cases for educators and parents could be of little consequence if appropriate action is taken, however if lawsuits continue then there will remain serious questions for the future of IDEA and how the children will be educated. EDUCATING STUDENTS WITH THE IDEA 6 Other further research that is needed in IDEA is the topic of inclusion. How will students with disabilities continue or begin to be included into general education classrooms. IDEA and section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act provide legal direction in the education of students with disabilities. Although neither IDEA nor 504 includes a specific requirement dictating inclusion in regular education classrooms, the LRE (Least Restrictive Environment) placement in both assumes a regular mainstream classroom placement for students in special education classifications. The legal mandates around IDEA and the 504 Act require that students with disabilities be placed in an appropriate learning environment that best fits their individual educational needs, which may or may not be in a general education classroom. Although research can be done to see which classrooms have a more positive effect on student learning, each student is different and the IEP’s provide a unique way for each student to learn. A student in an EBD (Emotionally/Behaviorally Disabled) classroom who receives an integrated academic program within a structured learning environment that includes a behavioral management program, may not find a “least restrictive environment” in a regular education math classroom. The educational placement intent of IDEA and 504 requires that school communities seek an inclusive education for students with disabilities, but only if that inclusion meets the IEP of the student. In many classrooms, inclusion is a diverse and complex situation for many special education students. Inclusion can range from total inclusion in regular education classes to partial inclusion in some classes. Inclusion in regular education classes for students with disabilities is driven by the student’s IEP needs. The intent of IDEA is to provide educational placements in regular education classrooms while meeting the individualized learning needs of each student. In closing IDEA has been designed to provide equitable and accessible education for students with disabilities. The IEP’s are the heart of the education of students with disabilities EDUCATING STUDENTS WITH THE IDEA 7 and the inclusion of those students in general education classrooms, depends on their IEP’s. Overall I felt that researching the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act helped me become more aware of why students with disabilities receive the services they are given. I also learned that though IDEA public schools have been able to help educate students who otherwise would be left on their own to find special private schools that would focus on teaching students with disabilities. IDEA also gives students different opportunities to learn including Response to Intervention or Early Intervening Services. The goal of the IDEA was to ensure that children with disabilities, not just receive education, but are provided the education in a general setting with other students. This process helps the inclusion of special education students into a general education school, so that the students with disabilities learn in a way similar to other students. In this way students with disabilities can feel that they were able to go to school and learn with their peers under equal and equitable circumstances. EDUCATING STUDENTS WITH THE IDEA 8 References Crockett, J. B., & Yell, M. L. (2008). Without data all we have are assumptions: Revisiting the meaning of a free appropriate public education. Journal of Law & Education, 37(3), 381392. Yell, M. L., & Shriner, J. G. (1997). The IDEA amendments of 1997: Implications for special and general education teachers, administrators, and teacher trainers. Focus on Exceptional Children, 30(1), 1-19. Yell, M. L., Ryan, J. B., Rozalski, M. E., & Katsiyannis, A. (2009). The U.S. Supreme Court and special education: 2005 to 2007. Teaching Exceptional Children, 41(3), 68-75. Yell, M. L., & Walker, D. W. (2010). The legal basis of response to intervention: Analysis and implications. Exceptionality, 18(3), 124-137. Zirkel, P. (2010). The legal meaning of specific learning disability for special education eligibility. Teaching Exceptional Children, 42(5), 62-67. Zirkel, P. (2011). What does the law say? Teaching Exceptional Children, 43(3), 65-67.