Annex 4: List of Documents Reviewed

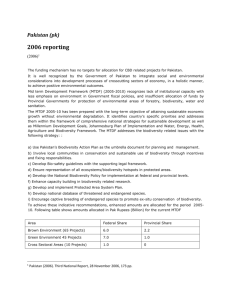

advertisement