Chapter 2 Overview of C Chapter Objectives 1. Present the origins of

advertisement

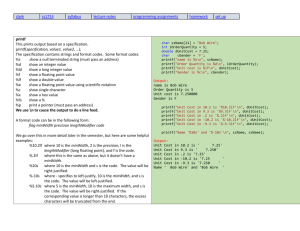

Chapter 2 Overview of C Chapter Objectives 1. Present the origins of the C language, and introduce the structure of simple C programs through the presentation of small sample programs. 2. Describe the simple data types int, double, and char. 3. Discuss the internal representations of type int, double, and char values. 4. Introduce the basic use of the input/output functions printf and scanf. 5. Present the preprocessor directives #include and #define. 6. Discuss the use of input and output format strings with placeholders for character and numeric data. 7. Introduce the proper use of comments as a means of program documentation. 8. Present the assignment statement along with the basic arithmetic operators and type casts and their use in writing simple arithmetic expressions. 9. Describe the process of writing simple programs that perform input, computation of numeric results, and output. 10. Introduce the problem of numerical inaccuracies in computations using type double values. 11. Review automatic and explicit conversion of data types. 12. Discuss input/output redirection and program-controlled files, and present the differences between interactive and batch processing of data. Notes and Suggestions Section 2.1. The beginning student often is confused about the difference between reserved words and standard identifiers, so you should emphasize the difference. Students will also benefit from a clear presentation of the two stages of the translation of a C program. If they understand the role of the preprocessor, they will see as reasonable the fact that a constant macro's value cannot be modified by a program. Emphasize the importance of choosing meaningful names for variables. If some students resist the extra typing required to enter meaningful names, you may want to prepare two versions of the same program, one with single-letter names and the other with meaningful names. Students will quickly see which is more readable. Section 2.2. Stress the meaning of the term "data type." Understanding this term early will make it easier for students to comprehend the concept of defining their own types. This section provides a brief introduction to the topics of internal representation of numbers and computational error. Students may be surprised to learn that computers do not perform real arithmetic calculations precisely. This is a very important point to emphasize now so that students will understand the benefits of using integers when possible. This text's use of type double rather than type float postpones students' recognition of some of the most obvious consequences of representational error. Refer students to the character codes in Appendix A when discussing this section. point out the gaps in the EBCDIC codes for alphabetic letters. Be sure to Section 2.3. Students often confuse the C assignment operator with the equal sign from algebra, which makes the statement x = x + 1; appear as nonsense. When you read an assignment statement aloud, always pronounce the = as "becomes" or "is assigned" to emphasize that the assignment statement's effect is to compute a value to be placed in the memory cell named by the variable on the left. In a similar vein, some students incorrectly view assignment statements as spreadsheet-like identities that automatically update the left side whenever the right side changes. Consider the following C statements: b = 2; a = b + 1; b = 3; printf("%d", a); A student who expects an output of 4 has fallen into this trap. When presenting the input/output functions scanf and printf, emphasize the differences between the input list of scanf and the output list of printf. We have intentionally delayed presentation of the input of strings so that at this point the & operator is required on all entries in scanf's input list. You should draw a picture of computer memory for a particular input/output statement sequence, and show students the difference between what scanf needs to know (i.e., addresses of variables) and what printf needs to know (i.e., the values to print). Also do exercises that stress the fact that the numeric format placeholders %d and %lf skip over blanks and carriage returns in the input, but the %c placeholder skips nothing unless it is preceded by a blank in the format string. Another instructive example is one in which a call to printf begins a line of output, but does not complete it with the \n escape sequence. The student should be aware that the output may not be displayed if the program terminates because of an error before the line is completed. Section 2.4. Beginning students of C, especially those who have taught themselves to program in another language, are frequently very resistant to principles of good program documentation and the importance of readability. "War stories" about the grief of maintenance programmers expected to update unreadable code or of your own former students who have encountered poor documentation in their first jobs will help to counter the notion that the only measure of a good program is whether it works. The following definition may help to put comments, meaningful names, and eyepleasing spacing in the proper perspective: A program is a document, part of which executes on a computer. Section 2.5. Stress that data types are abstractions for real-world data objects. Point out that we do not need to know the details of the representation of int, double, and char variables because we are provided with operators with which to manipulate these data types and functions with which to get and display values. Encourage students to use the step-by-step evaluation approach illustrated in Fig. 2.9 through Fig. 2.11 when they need to evaluate an expression containing more than one operator. Section 2.6. Remind students that when outputting numeric data using a placeholder with a specific field width, the field width is automatically increased to display a number whose magnitude is too large for the field. Students are often confused when they discover that the number of decimal places specified by a placeholder is absolute: the fraction is rounded to fit the field. Section 2.7. Before covering this section, investigate how the computer system the students use handles input/output redirection. Give students explicit instructions on how to run the batch program in Fig. 2.13. Section 2.8. Go over with students the precise output produced by your ANSI C compiler. Emphasize the differences between syntax errors, run-time errors, and result errors. New Terms Introduction C, 1972 UNIX AT&T Bell Laboratories Dennis Ritchie Section 2.1 comment preprocessor preprocessor directive #include #define library functions printf scanf <stdio.h> declarations executable statements constant macro standard libraries main prototype reserved words identifiers variable variable declaration data type identifier int void double char scientific notation ASCII printable character control character executable statement assignment statement assignment operator expression arithmetic operator input operation output operation input/output functions function call format string input list standard input device placeholder conversion specification address-of operator return statement print list escape sequence newline prompting message function argument user-defined identifier Section 2.2 collating sequence Section 2.3 Section 2.4 blank space program documentation Section 2.5 integer division remainder operator step-by-step evaluation mixed-type expression unary operator binary operator operator precedence rule associativity rule right associativity left associativity evaluation tree type cast round-off error mantissa exponent representational error cancellation error arithmetic underflow arithmetic overflow type conversion Section 2.6 field width right justified decimal places interactive mode batch mode echo print input/output redirection program-controlled file Section 2.7 Section 2.8 bugs debugging error message syntax error compilation error run-time error diagnostic message compiler listing logic error CHAPTER 2 SECTION 2.1 1. a. void, double, return b. printf c. MAX_ENTRIES, G d. time, xyz123, this_is_a_long_one e. Sue's, part#2, "char", #include 3. The preprocessor; #define and #include SECTION 2.2 1. a. 0.0103 1234500.0 123450.0 b. 1.3e+3 1.2345e+2 4.26e-3 3. double, int, char SECTION 2.3 1. Enter two integers> 5 7 m = 10 n = 21 3. My name is Jane Doe. I live in Ann Arbor, MI and I have 11 years of programming experience. SECTION 2.4 1. /* This is a comment? */ /* This one seems like a comment doesn't it */ SECTION 2.5 1. a. 22 / 7 is 3 7 / 22 is 0 22 % 7 is 1 7 % 22 is 7 b. 16 / 15 is 1 15 / 16 is 0 16 % 15 is 1 15 % 16 is 15 c. 23 / 3 is 7 3 / 23 is 0 23 % 3 is 2 3 % 23 is 3 d. 16 / -3 is ?? -3 / 16 is ?? 16 % -3 is ?? -3 % 16 is ?? (?? means the result varies) 3. a. 3 g. undefined m. -3.14159 b. ?? h. undefined n. 1.0 c. 1 i. ?? o. 1 d. -3.14159 j. 3 p. undefined e. ?? k. -3.0 q. 3 f. 0.0 l. 9 r. 0.75 (?? means the result varies) 5. a. white is 1.6666... c. orange is 0 e. lime is 2 b. green is 0.6666... d. blue is -3.0 f. purple is 0.0 7. underflow SECTION 2.6 1. printf("Salary is %10.2f\n", salary); 3. x..is....12.34....i..is..100 i..is..100 x..is..12.3 SECTION 2.7 1. Calls to printf to display prompts precede calls to scanf to obtain data. Calls to printf follow calls to scanf when data are echoed. Prompts are used in interactive programs but not in batch programs. Batch programs should echo input; interactive programs may also echo input.