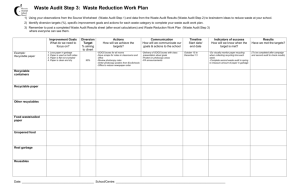

APPENDIX A (continued) Definitions of Assessed Audit Activities

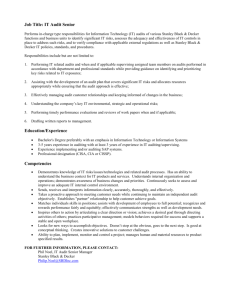

advertisement