WRITING UP A THEORY

advertisement

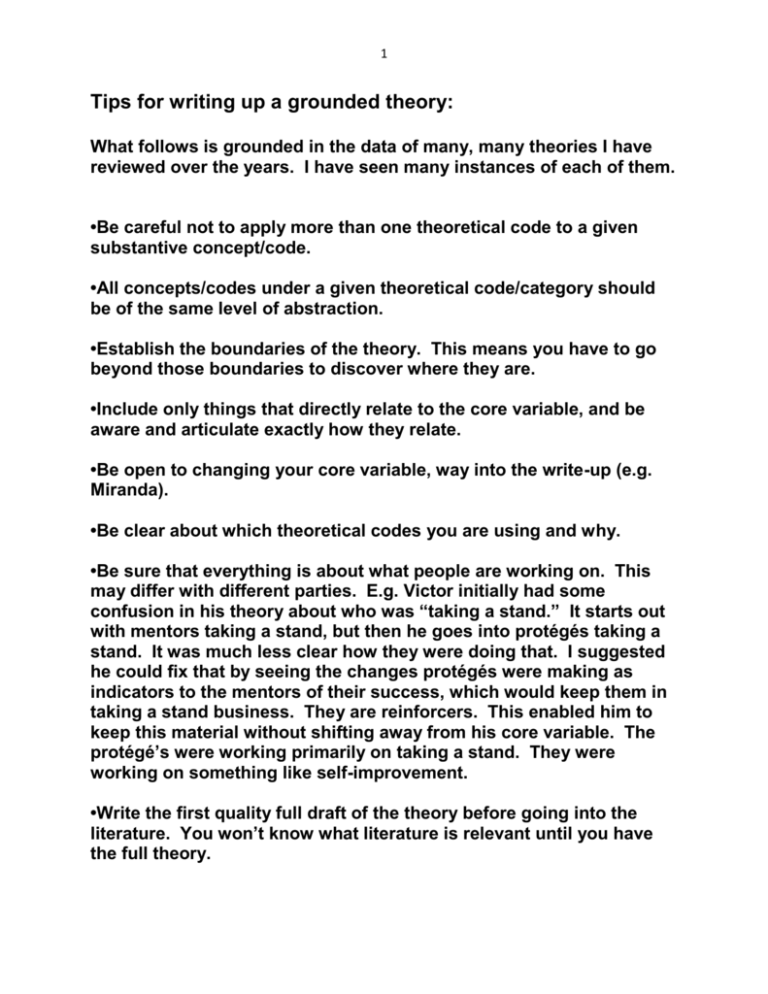

1 Tips for writing up a grounded theory: What follows is grounded in the data of many, many theories I have reviewed over the years. I have seen many instances of each of them. •Be careful not to apply more than one theoretical code to a given substantive concept/code. •All concepts/codes under a given theoretical code/category should be of the same level of abstraction. •Establish the boundaries of the theory. This means you have to go beyond those boundaries to discover where they are. •Include only things that directly relate to the core variable, and be aware and articulate exactly how they relate. •Be open to changing your core variable, way into the write-up (e.g. Miranda). •Be clear about which theoretical codes you are using and why. •Be sure that everything is about what people are working on. This may differ with different parties. E.g. Victor initially had some confusion in his theory about who was “taking a stand.” It starts out with mentors taking a stand, but then he goes into protégés taking a stand. It was much less clear how they were doing that. I suggested he could fix that by seeing the changes protégés were making as indicators to the mentors of their success, which would keep them in taking a stand business. They are reinforcers. This enabled him to keep this material without shifting away from his core variable. The protégé’s were working primarily on taking a stand. They were working on something like self-improvement. •Write the first quality full draft of the theory before going into the literature. You won’t know what literature is relevant until you have the full theory. 2 •Go into the serious academic theoretical literature, that comes out of scholarly fields such as sociology, social psychology, psychology. Don’t spend too much time in “literature light,” such as you find in the practicing professions literature. It will give your theory less credibility. E.g. systems literature found in KA guides, which pretty much ignores serious systems theory, like you can find in sociology. •Concepts not only carry imagery, they convey attitude. E.g. the U.S. government’s use of the concept, “descoping” to refer to Iraq reconstruction projects that are failing or have failed. Descoping involves redefining the limits of the contract to meet what has been done and eliminate what hasn’t been done, so they can claim the contract has been completed. Also, individual readers will bring their own interpretation to a concept, so you must be very careful in word choices and try to select the clearest most neutral words or terms possible to diminish the chances that readers will turn the concept into their own meaning, rather than what fits the data. •Avoid absolutes. They effectively shut down options for further discovery, as well as invite “put downs.” •Avoid making positive and negative judgment statements because they invite put-downs. •When writing about theory, write in the present tense. When writing descriptively about data, write in the past tense. •Use concepts, not analogies or metaphors. GT concepts have imagery, but treating them as if they are analogies or metaphors weakens them. •Remain open to more discovery (theoretical sampling) all the way to the end. Remain open even to changing the core variable (e.g. Miranda). The write-up is not a time to relax and stop thinking and discovering. Writing is a continuation of your analysis. As Glaser (Theoretical Sensitivity, p. 7) said, “Grounded theory assumes that part of the method, itself, is the writing of a theory.” •Don’t include concepts or terms that are not part of your theory/explanation. E.g. including face sheet variables (age, gender, 3 educational level, etc.) in your theoretical write-up will imply that these are causal variables. However, readers who don’t understand that grounded theory is about behavior, not people, will probably want to see these categories mentioned. If you feel it is necessary to do that, do it in the introduction to your dissertation (not your theory), and make it clear that you are doing so only to establish context. Only if they actually are variables in your theory should you say anything more. If none of them are, which in all likelihood will be the case, make that clear. •You should use the same formatting for concepts that are on the same level of abstraction. E.g. if you develop sub-sections to portray sub-categories of one concept, you must do it for all concepts on that level of abstraction. If you don’t it may appear that you have weak spots or holes in your theory, or that the concepts are not really on the same level of abstraction (even if they are). •It is helpful to italicize concepts when you introduce and define them, but don’t italicize them throughout the text because it reduces the flow of the text for the reader and can make the theory feel contrived. •If you incorporate theoretical codes such as “property,” “dimension,” or “condition” make sure you use them accurately, i.e. that what you are referring to as a property is actually a property, what you are referring to as a dimension is actually a dimension, and what you are referring to as a condition is actually a condition. It is easy to confuse such terms, so you must think deeply about their use. •It is sometimes unnecessary and even cumbersome to continually preface concepts/material with a theoretical code (e.g. property, dimension). Once you have introduced and identified something with its relevant theoretical code, it is usually not necessary to keep prefacing each use of that word with the theoretical code. It clutters up the sentence and therefore muddies the meaning. It can be likened to leaving up some of the scaffolding on a building after construction has been completed. For example, once you have introduced something as a property, you don’t need to continue prefacing each use of the word with phrases such as, “the property of.” 4 •Word selection is extremely important, not only in naming your concepts, but writing up your theory. Re you concepts, the word or phrase you choose to represent a pattern from the data essentially “is” the data for the reader. A word/phrase that doesn’t perfectly fit in effect un-grounds your theory. The theory is grounded partially in whatever meaning you and/or readers bring to it—i.e. it becomes more constructivist than it should. •Be cognizant of how you use conjunctives. E.g. if you write something like, “it is the property of cultivating” you are effectively saying that whatever it is is the only property of cultivating (which means that it is cultivating, only expressed with another word). This shuts your theory down. If you write “it is a property of cultivating,” all options remain open. Another example: if you write “poor communication weakens the organizational effectiveness” versus “poor communication weakens organizational effectiveness.” The first sentence with “the” inserted implies you are writing about a particular organization. Without “the” makes it a general theoretical statement, rather than a mere substantive one. •You should include only words that are necessary to convey your basic intended meaning. You should avoid including “add on” words that are inconsequential to that meaning, even if they sound nice. Every word should have an identifiable purpose. A cluttered text will obscure your theory. •Be mindful about how you use adverbs like “hence,” “therefore,” “thus,” “so,” etc., particularly to open a sentence (I commonly see this). Such words contain implicit or explicit propositions/equations. They effectively say that what follows is related to what came before. Particularly when writing up a theory. You don’t want to imply relationships where they don’t exist or mislead the reader into thinking you are establishing a relationship when you are not intending to do so. •Be cautious in your use of superlatives. You may lose credibility with reader if you use extreme words and statements. Superlatives are usually exaggerations of what is really going on. Most things occur within a range. Although extremes may occur at the edges of 5 that range, they are seldom representative of the norm. It is okay to use superlatives in the context of that range, but not out of context of the range. •Introduce and discuss your concept or theoretical idea first, then give examples from your data to illustrate it, not the reverse. If you give the example first, your text will read as primarily description rather than theory. Your theory will get lost in the description. This is the way it is done in QDA (qualitative data analysis), which focuses more on description rather than theory. •Be cautious of drawing inferences from your data, particularly if they are related to motives. Inferential leaps are inappropriate for GT. •Don’t get too context specific. Abstract. E.g. collapse gender, age, etc. into a category such as “personal attributes.” •Anything pattern/variable, condition, or whatever used in an hypothetical probability statement should be “named” (expressed conceptually), if possible, otherwise the hypothetical probability statement will remain hidden to the reader. If something isn’t nameable, it probably doesn’t belong in a hypothetical probability statement. If you fail to fully articulate things conceptually, you lose the value of having hypothetical probability statements and strand yourself between conceptual description and a fully developed grounded theory. •When introducing or discussing concepts, begin the discussion with the conceptual/theoretical point and then example it. Do not lead with an example. •When writing up a theory, unless it is overdone and begins to feel contrived, it is usually a good idea to use gerunds when conceptualizing action. •As Glaser and Strauss said, a theory is a theory because it explains something. It not only explains phenomena (in GT that would be the core variable/category) in general, it explains variations. Variations can be stated in hypothetical probability form. If there are no discernible hypothetical probability statements in your write-up, the 6 explanatory power of your theory will be weak. The absence of hypothetical probability statement likely indicates that your write-up is more conceptual description than full explanatory theory. A conceptual description is essentially a list of concepts followed by description, with minimal integration between the concepts. •Make sure that each sentence contains only one subject, unless it is intended to be a list of similar subjects. Example of what not to do: “According to Glaser (1967), the researcher begins with a general area of interest, and attempts to gain a theoretical foothold.” Example of okay sentence: “According to Glaser (1967), the researcher begins with a general area of interest, data collection, constant comparative analysis, and theoretical sampling.” •If your theory is a process theory it must have at least two stages. Not only must you discuss each stage, you must also depict how the process moves from one stage to another. And, you must discuss shape. Is it linear (begins at stage one and ends at the last stage in the process)? Is it recursive, circular, or whatever? You will probably need to introduce and maybe even discuss the stages in a linear order, but you still need to make the shape of the process clear. For example, most discussions of the grounded theory process introduce and discuss each stage in linear order, although the process itself is not linear. As Glaser said, “The detailed, conceptual grounded route from data collection to a finished writing is a process composed of a set of double-back steps.” (Theoretical Sensitivity, p. 16) •The write-up of your theory should follow your theoretical outline (that’s what it is for). So, your section and sub-section headings should parallel your theoretical outline. •Glaser is dead-set against including diagrams in a theory write-up. He thinks they distract from the theory and invite the reader to shortcut. Because they are bare bones, they also open the door to misinterpretation and imported ideas. Glaser maintains that if you need a diagram, there must be something inadequate about the writeup of your theory. He acknowledges that diagrams can be useful to the analyst when they are trying to piece their theory together. But the analyst is far more familiar with the data and emerging theory than 7 readers so they can remain honest to the data. I tend to agree with Glaser about all of this. However, I think that diagrams can be useful in a summary section or appendix. By this time the reader has encountered them, and they will have read and digested the theory. At that point a diagram may help refresh their understanding and help them to better remember the theory, bypassing all of the potential problems I mentioned above. Proprietary Not for distribution without permission of Odis E. Simmons, Ph.D. osimm@comcast.net or osimmons@fielding.edu 1-253-549-2267