Document 6641760

advertisement

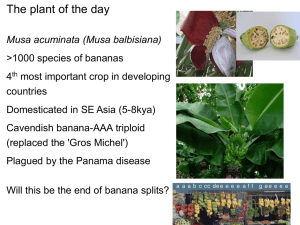

POLYPLOIDY This assignment involves the exploration of the topic of polyploidy. Your task is to utiluize the resources below and produce a Prezi/powerpoint or poster from Glogster. The questions you are to address are the following: What is polyploidy? What are some sample chromosome arrangements in polyploidy? What are some examples of polyploid organisms? What are some mechanisms of polyploidy? (at least 2) How is polyploidy involved in the production of “seedless” varieties of fruits and vegetables? How can polyploidy contribute to speciation (2 examples)? What is one advantage and one disadvantage of polyploidy? 5 fabulous facts about polyploidy. Suggested Resources: Feel free to find others but these are good basic sescriptions: http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/polyploidy-1552814 http://www.polyploidy.org/index.php/Information:How_are_polyploids_formed http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z6W2dhLRhw0 http://waynesword.palomar.edu/hybrids1.htm The following information is from (http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/P/Polyploidy.html) Polyploidy in plants Polyploidy is very common in plants, especially in angiosperms. From 30% to 70% of today's angiosperms are thought to be polyploid. Species of coffee plant with 22, 44, 66, and 88 chromosomes are known. This suggests that the ancestral condition was a plant with a haploid (n) number of 11 and a diploid (2n) number of 22, from which evolved the different polyploid descendants. In fact, the chromosome content of most plant groups suggests that the basic angiosperm genome consists of the genes on 7–11 chromosomes. Domestic wheat, with its 42 chromosomes, is probably hexaploid (6n), where n (the ancestral haploid number) was 7. Some other examples: Probable ancestral Chromosome Plant haploid number number domestic oat 7 42 Ploidy level 6n peanut 10 40 4n sugar cane 10 80 8n banana 11 22, 33 2n, 3n white potato 12 48 4n tobacco 12 48 4n cotton 13 52 4n apple 17 34, 51 2n, 3n Polyploid plants not only have larger cells but the plants themselves are often larger. This has led to the deliberate creation of polyploid varieties of such plants as watermelons, marigolds, and snapdragons. POLYPLOIDY Polyploidy and Speciation When a newly-arisen tetraploid (4n) plant tries to breed with its ancestral species (a backcross), triploid offspring are formed. These are sterile because they cannot form gametes with a balanced assortment of chromosomes. However, the tetraploid plants can breed with each other. So in one generation, a new species has been formed. Polyploidy even allows the formation of new species derived from different ancestors. In 1928, the Russian plant geneticist Karpechenko produced a new species by crossing a cabbage with a radish. Although belonging to different genera (Brassica and Raphanus respectively), both parents have a diploid number of 18. Fusion of their respective gametes (n=9) produced mostly infertile hybrids. However, a few fertile plants were formed, probably by the spontaneous doubling of the chromosome number in somatic cells that went on to form gametes (by meiosis). Thus these contained 18 chromosomes — a complete set of both cabbage (n=9) and radish (n=9) chromosomes. Fusion of these gametes produced vigorous, fully-fertile, polyploid plants with 36 chromosomes. (They had the roots of the cabbage and the leaves of the radish.) These plants could breed with each other but not with either the cabbage or radish ancestors, so Karpechenko had produced a new species. The process also occurs in nature. Three species in the mustard family (Brassicaceae) appear to have arisen by hybridization and polyploidy from three other ancestral species: B. oleracea (cabbage, broccoli, etc.) hybridized with B. nigra (black mustard) → B. carinata (Abyssinian mustard). B. oleracea x B. campestris (turnips) → B. napus (rutabaga) B. nigra x B. campestris → B. juncea (leaf mustard) Modern wheat and perhaps some of the other plants listed in the table above have probably evolved in a similar way. Polyploidy in animals Polyploidy is much rarer in animals. It is found in some insects, fishes, amphibians, and reptiles. Until recently, no polyploid mammal was known. However, the 23 September 1999 issue of Nature reported that a polyploid (tetraploid; 4n = 102) rat has been found in Argentina. Polyploid cells are larger than diploid ones; not surprising in view of the increased amount of DNA in their nucleus. The liver cells of the Argentinian rat are larger than those of its diploid relatives, and its sperm are huge in comparison. Normal mammalian sperm heads contain some 3.3 picograms (10-12 g) of DNA; the sperm of the rat contains 9.2 pg. Although only one mammal is known to have all its cells polyploid, many mammals have polyploid cells in certain of their organs, e.g, the liver. [More]