Malaria Control Program at PATH Working Paper on Accelerating

advertisement

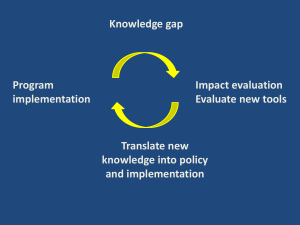

Malaria Control Program at PATH Working Paper on Accelerating Program Progress toward Transmission Elimination in Africa This working paper summarizes findings, experience, and analysis resulting from the efforts of a wide range of national, regional, and global malaria experts. It is intended to provide an updateable reference point for discussion at a time of rapid change in our understanding of how to eliminate malaria in African countries. The several African countries currently targeting elimination have mobilized actions relatively recently; while scientific evidence and experience from previous and current efforts in countries outside of Africa are informing program planning and implementation, much of what is being done today to develop a robust evidence base on how to eliminate the disease in Africa is a result of consultation, analysis, and guidance from a wide range of Roll Back Malaria partners. Technical guidance, practical experience, and leadership from African governments, national ministries of health, their malaria programs, and their partners at the country level are providing critical lessons to shape the path ahead. Today is a time of rapid change and there is much to be learned about how to optimize efforts and sustain commitment to eliminating malaria in Africa. Introduction and background The world has made remarkable progress in controlling malaria in that past half-century. The Global Malaria Eradication Program (GMEP), launched by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1955, was the first concerted effort to stop the disease in the 143 malaria-endemic countries. By 1978 it was successful in freeing 37 countries from malaria and reducing the disease burden in many others, although African countries did not benefit from these efforts out of recognition by the WHO African Regional Committee that the strategies and tools could not be effectively implemented in the region. Challenges including drug and insecticide resistance eroded confidence in GMEP efforts and it was abandoned in 1969. By the late 1990s, ten countries—most in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region— successfully eliminated malaria, while the malaria situation deteriorated in other parts of the world. This period also was characterized by a re-energized commitment to developing new tools, including insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs), artemisinin-based combination therapies, and diagnostics. Establishment of the Roll Back Malaria (RBM) Partnership in 1998 launched an era of concerted effort to halt malaria in African nations. Progress toward elimination continued during the most recent decade; in that time, four countries were certified by WHO as having eliminated the disease and every WHO region of the world demonstrated improvements in reducing disease burden. Also during this era, the scale-up for impact (SUFI) approach was tested and proven as a strategy to rapidly implement prevention interventions that achieve health impact. The success of SUFI led to wide adoption of this approach across the Africa region with strong support from the RBM Partnership; US President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI); the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; and the World Bank. During the last decade SUFI has become the strategic approach implemented by more than 40 countries in the region. With the early successes demonstrated by SUFI, Bill and Melinda Gates convened the Gates Malaria Forum in 2007 and put malaria elimination and ultimate eradication back on the global stage. WHO director general Margaret Chan strongly supported the endeavor, prompting considerable discussion and debate in the global malaria community. In 2009, the RBM Partnership’s Global Malaria Action Plan 1 was launched, describing the path from scale-up through elimination, one that is dependent on sequential reduction of malaria transmission within each program step (from SUFI, through sustained control, pre-elimination, and elimination). The Malaria Elimination Group (MEG) established a series of meetings and publications on issues of malaria elimination and WHO published guidance and restated the certification process for national malaria elimination. Since 2007, several African countries have announced their intent to eliminate malaria, including countries in the Southern Africa Development Community, which joined the sub-regional malaria elimination initiative in Southern Africa known as the Elimination Eight. The WHO African Region adopted a resolution in 2009 to accelerate control to achieve malaria elimination. In response to the suggestion that new and better tools and strategies would be required to ultimately achieve global malaria eradication, the Malaria Eradication Research Agenda (malERA) Group detailed the research agenda to accomplish this. In 2010 the World Health Organization convened malaria experts from diverse backgrounds to examine options for next steps in further controlling malaria transmission and explore opportunities for eliminating the disease in African communities with existing tools. The group detailed and endorsed the concept of strengthened information systems and community leadership and responsibility to seek and contain malaria transmission. A view today toward malaria transmission elimination Today, nearly one third of all remaining malaria-affected countries are on course to eliminate the disease in the next decade. We know that SUFI is not a comprehensive approach to malaria control but represents a strategy to launch comprehensive malaria programming en route to elimination. Country experience is demonstrating that success in rapidly scaling up malaria control intervention coverage, while capable of dramatic impact on mortality and illness rates, does not constitute a sustainable program strategy. Country progress in achieving low or very low transmission rates is laudable, but it is not an endpoint. The persisting financial, development, and human cost of malaria, even when the disease becomes very rare, is unacceptable. Only by eliminating malaria can countries end the burden associated at all levels of transmission. The RBM partners currently face several important challenges to continuing the expansion of program scale-up to the entire Africa region—especially in large countries where large numbers of malaria deaths continue to occur—and to implementing effective strategies to extend the gains of scale-up that will progressively reduce malaria transmission to zero, thus eliminating the disease. The Malaria Control and Evaluation Partnership in Africa (MACEPA), a program within PATH’s Malaria Control Program, is partnering with several African countries to lead the development of effective program strategies to guide progression along the spectrum from scale-up to elimination. Documenting strategies and lessons from countries building on SUFI to move toward elimination is providing critical guidance on how malaria transmission can be systematically reduced and eventually halted. The pathway to malaria transmission elimination The progression from high malaria transmission to elimination is a process that requires continual adjustments to programming across the evolving epidemiological spectrum to ensure attention to detecting and treating increasingly rare instances of infection (Figure 1). As these epidemiologic steps are reached— presented here as ten-fold reductions—programmatic adjustments must be made based on the extent to which the added or modified intervention or the intensified resource investment will further reduce malaria transmission. Once a SUFI approach to programming has succeeded in reducing infection transmission through vector control (killing or shortening the life of female mosquitoes so that they are not able to transmit infection), the focus must incorporate the balance of clearing malaria 2 parasites from symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals so that they do not transmit parasites back to mosquitoes. Success in moving toward infection elimination today is based on the assumption that progress can be made by deploying existing interventions, tools, and systems; building on malaria program infrastructure; and transitioning much of the orientation of a national program to incorporate the spectrum from centralized leadership to community-based action where each level of the malaria program and the health care system has critical responsibilities for the work. Key concepts about malaria transmission It is highly variable across Africa. While most countries are broadly considered “malariaendemic” and their populations are at high risk for malaria, there is a very wide range of transmission intensity and it is important to assess where populations are on the spectrum so that appropriate strategies can be applied. It is measured by the frequency of infections in the human population. Historically, this has been presented as the entomologic inoculation rate (EIR)—the number of infectious mosquito bites per person per time interval (typically per year). This is translated into a rate of infections per 1,000 population per year. It is a circular process—from mosquitoes to humans and then back to mosquitoes—and transmission reduction must attack both arms of the circle. To date, highly effective vector control tools (long-lasting insecticide treated nets [LLINs] and indoor residual spraying of insecticide [IRS]) have proven to have a dramatic impact on both processes, leading to about a ten-fold reduction in transmission under current program implementation efforts. Malaria parasites can be transmitted and harbored by someone who feels and appears healthy. While prompt diagnosis and treatment of malaria cases is critical for the individual who is sick with malaria, many infected people are not symptomatic and so do not seek treatment. Frequently, this leaves a large population of asymptomatic, infected people able to infect mosquitoes. For each step in transmission control the objective is to achieve further reductions in the remaining reservoir of malaria parasites, and consequently the source of further transmission in the population—either addressing the mosquito-to-human process or the human-to-mosquito process. Program actions must be able to respond to rapidly changing transmission. The rate at which malaria transmission can change is dramatic and programs must be ready to Malaria transmission and impactprograms on populations and success programming respond accordingly. For example, achieving rapid in transmission reductionfrom through population-based community and treatment will need to Progression scale-up to elimination can be screening characterized as a multi-step process (Figure 1). In quickly transition to a strategy that prioritizes rapidly identifying and treating isolated new programmatic terms this has been characterized in the RBM Global Malaria Action Plan as beginning and screening in the vicinity who may have effort been exposed. withinfections SUFI, progressing to aindividuals consolidated and sustained control and then transitioning toward elimination. Each step builds on the progress achieved from existing program action; and each step must lead to progressive and substantial transmission reduction. Figure 1 illustrates the single path from high to no malaria transmission. It highlights the probable population experience with malaria infections and illness and summary program actions and evolving pattern of interventions required as a community, district, or province transitions along the path toward decreasing transmission. To progress along the malaria elimination spectrum, countries require accurate, real-time data on the disease’s epidemiological profile. The intensity of malaria transmission has important implications for timing and configuring the strategies required to bring about further reductions. 3 Figure 1. Malaria transmission reduction: Population experience and intervention strategies for progress In settings where initial transmission is high there still may be much variability in transmission intensity. For example, a country may have implemented an excellent SUFI program that reduces transmission ten-fold, but still there persists an entomologic infection rate (EIR) of five to ten or greater, parasite prevalence may remain high,1 and morbidity and mortality persist. Thus, the progress in transmission reduction will require continued attention to the ongoing levels of infection in the population and continued evolution of interventions to address the level and focus of that transmission. Programmatic components of malaria elimination Strategic program design is critical to success regardless of where a program falls along the elimination spectrum (Figure 2). Required actions can be organized into three general areas of focus. The first is about leadership: addressing governance; resourcing; guidance on policy, procedure, and strategy; and human resource needs. The second is about strengthening local program action with an emphasis on optimizing existing intervention coverage and the required supply systems and a new emphasis on finding and clearing parasites from all people, and the building of robust surveillance systems and community action. The third is about documenting progress in transmission reduction and finding or using new tools that will contribute specifically to that success. 1 Because parasite prevalence is determined by both incidence and duration of infection, long duration asymptomatic infections (untreated) may contribute to persistent high parasite prevalence even when incidence has been markedly reduced. 4 Figure 2. Programmatic components of malaria elimination Mobilize national leadership Engage districts and communities Strengthen surveillance information systems Address key issues (including governance; resourcing; guidance on policy, procedure, strategy; and HR needs) Optimize prevention intervention coverage Identify and test new strategies and tools Track transmission Reduce parasites in human populations Strengthen local programs Maximize impact and document progress and factors contributing to success Mobilize national leadership Durable national commitment at the highest levels is required for countries to succeed in eliminating malaria. A sustained commitment to providing leadership and resourcing on policy, strategy, and implementation are critical at each stage on the pathway to elimination. Engage at the district and local levels Country success also depends on sub-national capacity for and acceptance of the concept and specific approaches to be undertaken for malaria transmission reduction leading to elimination. Engagement efforts will need to focus on technical skills, program capacity, and supply chain systems that are critical for scaling up the elimination effort. Develop or strengthen a malaria infection-detection surveillance system A key element of an effective transmission reduction effort is the development of a data collection system to inform metrics for planning and measuring progress. This system requires diagnostic confirmation with available methods (rapid diagnostic tests [RDTs] and microscopy) at the local level; results comprise the core data for directing transmission reduction work and for tracking progress in lowering transmission and so must be made readily available (it will also serve as the basis for fever management). Optimize prevention intervention coverage There is limited experience and guidance on optimizing intervention mix and coverage for maximum benefit and cost-effectiveness.2 There are no pre-defined coverage levels to achieve lowest possible malaria transmission levels. While progressively reducing transmission might seem to suggest the appropriateness of ever-increasing interventions used and coverage rates sought, growing evidence 2 RBM identifies the standard prevention interventions as long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) strategies in pregnant women, and possibly in infants, and seasonally in children. 5 from both field experience and modeling suggest, for example, that 100 percent coverage with ITNs is not necessarily required for maximal benefit. This optimization process needs to be based on systematic assessment of existing transmission intensity and an iterative process of examining the benefit of an added intervention versus the benefit of improving on coverage with an existing intervention. As transmission is dramatically reduced and quality, timely surveillance, and response is improved in a country, using surveillance as an intervention may replace or supplement existing strategies and contribute importantly to final steps of transmission elimination. Implement diagnosis and drug therapy strategies to locate and eliminate the human reservoir of parasitemia Strategies for accomplishing this may vary. In some instances, a campaign-style mass drug administration effort may be appropriate to presumptively treat everyone in a community where cases are known to be present. A screen and treat approach (also known as active infection detection) may be used to screen entire populations or focal areas where cases are identified and to treat all infected persons. Alternately, active investigation of transmission based on infection identification could be implemented, in which those living in or near a household where an infection is found are tested and treated when necessary. All strategies share in common the goal of reducing transmission, then driving it to a very local level, and eventually eliminating transmission altogether. Identify and test new tools and strategies Several countries achieved strong impact with SUFI and are now testing strategies for malaria elimination. These early efforts are already providing important lessons from which others can learn. Similarly, while current tools are understood to be sufficient to achieve elimination, new ones will be available soon that can be tested and implemented. Assess progress toward transmission elimination This is based on the strengthened surveillance system output to monitor transmission intensity with occasional population surveys to monitor program inputs, coverage, and use. Attention must be given to assessing service delivery feasibility, cost, and evolving benefits in morbidity, mortality, and socioeconomic conditions. Key program considerations for achieving malaria control The proposed conceptual framework detailed here offers a definable and measurable strategic orientation for malaria elimination that will lead to predictable and progressive reductions in malaria transmission in Africa, building on the systems and gains already established with SUFI. There is much to be learned and there are many challenges ahead. Critical questions will need to be resolved in the relatively near term to leverage support for and guide programming, including the following: 1. When is it appropriate for a country to embark on malaria elimination? Many countries have already declared their intention to seek elimination. While some external experts may think this is premature for certain countries (for example large countries with high parasite prevalence and transmission rates and constraints on programmatic capacity), early encouragement to start and learn may be important for the long path that they will need to take. 2. Where is it most logical to begin testing elimination strategies? It stands to reason that the first steps should be taken both in areas where success is most likely (because the program will need 6 early success to gain a sense that this can be done) and in areas where it will be most difficult (because the program will need to be there eventually and need to strengthen weak systems that make these areas problematic now). 3. What is the optimal size of malaria-free zones and the relevant border of the zone for protection from reintroduction? The size is of local relevance—it should be big enough to be credible as a replicable effort that could achieve national scale, but small enough to manage in the early days. And, one should attend to both the lowest transmission settings and the settings that are most likely to reintroduce malaria to the elimination area. Coalescing malaria-free zones into a national elimination effort will begin the end-game of elimination. 4. How can programs move rapidly along the elimination spectrum while maintaining quality? Building on progress attained through SUFI, the population will still have much immunity and be at least partially protected from severe disease and death; this will have distinct advantages for rapid continued efforts toward transmission elimination. The time required for programs to progress to elimination has important cost implications; the desire to progress rapidly will need to be balanced with the need to assemble solid, effective programs. Further, clear progress toward malaria elimination needs to occur in a timely manner to build and sustain commitment. 5. How is progress measured and promoted when there is very little malaria? The measurement metric (and its evolution under changing epidemiological conditions) needs to be established in order to demonstrate the extent of progress in malaria elimination and to galvanize sustained support for ongoing efforts among communities, thought leaders, donors, and global leaders in malaria. 6. What are critical potential impediments that need to be addressed to support smooth progression to elimination? Potential barriers include interrupted funding flows, quality control issues, or waning top-level support for programming. Challenges at the global and country level will be ongoing and accruing country action and experience will help address some of the anticipated concerns: Demonstrating that it can be done in one “large enough” setting in malaria-endemic Africa will present an enormous challenge and debate among the global community. Identifying and improving the critical health systems such as procurement and supply chain management, information collection, and analysis for action will help the global community prioritize its investment. Clarifying the value-for-investment of malaria elimination. Cost-effectiveness studies of full program actions are needed to generate data that can substantiate the financial case for investing in malaria elimination. This will likely be critical to assure ongoing national and external financing of the elimination agenda. 7 Selected bibliography Roll Back Malaria Partnership. Eliminating Malaria: Learning from the Past, Looking Ahead. Progress & impact series, report #8. Geneva, 2011. Pampana E. A textbook of malaria eradication. Oxford University Press, London, 1963. Najera JA. Malaria control: achievements, problems and strategies. Geneva, WHO, 1999 (WHO/CDS/RBM/99.10) Steketee RW, Campbell CC, 2010. Impact of national malaria control scale-up programmes in Africa: magnitude and attribution of effects. Malar J 9: 299. Roll Back Malaria Partnership. Global malaria action plan. Geneva (2008). Das P, Horton R. Malaria elimination: worthy, challenging, and just possible. Lancet 2010; published online Oct 29. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61551-6. (http://www.thelancet.com/malaria-elimination) Feachem RGA, Phillips AA, Targett, GA, Snow RW. Call to action: priorities for malaria elimination. Lancet 2010; published online Oct 29. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61500-0. (http://www.thelancet.com/malaria-elimination) Baird JK. Eliminating malaria—all of them. Lancet 2010; published online Oct 29. DOI:10.1016/S01406736(10)61494-8. (http://www.thelancet.com/malaria-elimination) Marsh K. Research priorities for malaria elimination. Lancet 2010; published online Oct 29. DOI:10.1016/S01406736(10)61499-7. (http://www.thelancet.com/malaria-elimination Feachem RGA, Phillips AA, Hwang J, et al. Shrinking the malaria map: progress and prospects. Lancet 2010; published online Oct 29. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61270-6. (http://www.thelancet.com/malaria-elimination) Tatem AJ, Smith DL, Gething PW, Kabaria CW, Snow RW, Hay SI. Ranking of elimination feasibility between malariaendemic countries. Lancet 2010; published online Oct 29. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61301-3. (http://www.thelancet.com/malaria-elimination) Moonen B, Cohen JM, Snow RW, et al. Operational strategies to achieve and maintain malaria elimination. Lancet 2010; published online Oct 29. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61269-X. (http://www.thelancet.com/malariaelimination) Sabot O, Cohen JM, Hsiang MS, et al. Costs and financial feasibility of malaria elimination. Lancet 2010; published online Oct 29. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61355-4. (http://www.thelancet.com/malaria-elimination) World Health Organization. Global malaria control and elimination: report of a technical review. Geneva, 2008. World Health Organization. Informal consultation on malaria elimination: Setting up the WHO agenda. Geneva, 2006. World Health Organization. Malaria elimination: A field manual for low and moderate endemic countries. Geneva, 2007 World Health Organization. Community-based Reduction of Malaria Transmission. Geneva, 2011. Sambo LG, Ki-Zerbo G, Kirigia JM. Malaria control in the African Region: perceptions and viewpoints on proceedings of the Africa Leaders Malaria Alliance (ALMA). BMC Proceedings, 2011. Alonso PL, Brown G, Arevalo-Herrera M, Binka F, Chitnis C, Collins F, Doumbo OK, Greenwood B, Hall BF, Levine MM, Mendis K, Newman RD, Plowe CV, Rodríguez MH, Sinden R, Slutsker L, Tanner M, 2011. A research agenda to underpin malaria eradication. PLoS Med 8: e1000406. Campbell CC, Steketee R. Malaria in Africa can be eliminated. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011 vol. 85 no. 4 584-585. 8