THE EFFECT OF SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS ON OPTIMAL SLEEP AND SELFREPORTED HEALTH STATUS

A Thesis

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Sociology

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

Sociology

by

Kimberly Herd

SUMMER

2013

©2013

Kimberly S. Herd

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

THE EFFECT OF SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS ON OPTIMAL SLEEP AND SELFREPORTED HEALTH STATUS

A Thesis

by

Kimberly Herd

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Jacqueline Carrigan, Ph.D.

__________________________________, Second Reader

Ellen Berg, Ph.D.

___________________

Date

iii

Student: Kimberly Herd

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University

formal manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to

be awarded for the thesis.

_____________________________, Graduate Coordinator

Amy Qiaoming Liu, Ph.D

Department of Sociology

iv

________________

Date

Abstract

of

THE EFFECT OF SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS ON OPTIMAL SLEEP AND SELFREPORTED HEALTH STATUS

by

Kimberly Herd

Prior research affirms that social determinants, particularly socioeconomic status

(SES) play a vital role in determining the health of individuals. While many studies show

that lower SES relates to lower levels of health, few discuss the role of sleep in relation to

SES and health. Particular interest in sleep has emerged in response to changing work

patterns, the economy and sleep related illness. This study looks to assess the role of SES

in relation to sleep quantity and the role of sleep quantity in relation to health. Data from

the 2011 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) were used for analysis in this study.

The NHIS data is collected by the U.S. Census Bureau and used by the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) track and analyze health data in the U.S. While

the demographic data showed that the majority of respondents get optimal amounts of

sleep and have good health, logistic regression analysis of the 2011 NHIS data reveals

v

that specific characteristics are predictive of optimal sleep for adults including education,

gender, race, marital status, and employment. Multiple regression analysis shows that

both SES and optimal sleep are significant factors in determining self-reported health

status. In addition, age, marriage, employment, and race are significant factors in

determining self-reported health status.

_____________________________, Committee Chair

Jacqueline Carrigan, Ph.D.

________________

Date

vi

DEDICATION

This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Donald and Suzanne Herd, my biggest fans. Many

thanks for all of your support and patience through this lengthy process. It was through

your encouragement and belief in my abilities that I have been able to make my

education a priority and persevere under the numerous challenges and responsibilities

that life brings us. I want to thank you for never giving up on me even in the darkest

days. Dad, thank you for believing in me and always encouraging me to do anything I set

my mind and heart to do. Mom, thank you for being the best teacher and mother anyone

could ever ask for. Mom and Dad, thank you for your endless love and understanding.

I’d also like to thank my friends, work, and church families for their encouragement and

support during this process. Although I didn’t always see it, they saw my strength and

determination from afar. They believed in me so that I could believe in myself. For all

of this, I am truly grateful.

vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Jackie Carrigan, Ph.D. for her guidance, expertise and patience.

Thank you for allowing me to pop into your office and email you whenever I had

questions or concerns throughout this process. Her knowledge and expertise with

statistics, data analysis, and insight regarding social stratification were invaluable. Thank

you for being my chairperson and for all of your assistance throughout my graduate

education.

I would also like to thank Ellen Berg, Ph.D. for being my second reader. Not only did

your encouragement help during my first semester as a graduate student, becoming my

second reader on a moment’s notice really meant a great deal to me.

Finally, I would like to thank the CSUS Sociology Department for providing me with

invaluable experiences and an excellent graduate education. Thank you for taking the

time to meet with me and answering all of my questions. This has been one of the best

experiences of my life and I want to thank you all for this amazing opportunity and

believing in my abilities.

viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Dedication…………………………………………………………………. vii

Acknowledgements………………………………………………………… viii

List of Tables………………………………………………………………. xi

Chapter

1.

INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………… 1

2.

LITERATURE REVIEW……………………………………………. 5

Health and the Social Gradient…………………………………… 5

Defining SES and Social Determinants of Health……………….... 6

SES and Health…………………………………………………… 8

Mediators of the Relation between SES and Health……………… 9

Sleep………………………………………………………………. 11

Sleep and Health…………………………………………………… 12

The Effects of SES on Sleep………………………………………. 13

Mediators of the Relation between SES, Sleep, and Health………. 16

3.

METHODOLOGY……………………………………………………. 19

Variables………………………………………………………........ 19

Sleep……………………………………………………… 19

Health status………………………………………………... 20

Socioeconomic variables……………………………………20

ix

Data analysis procedures……………………………………………22

4.

RESULTS……………………………………………………………...23

5.

DISCUSSION……………………………………………………….... 32

Strengths and Limitations………………………………………...... 37

Areas of Further Research………………………………………..... 38

References………………………………………………………………..... 39

x

LIST OF TABLES

Tables

1.

Page

Descriptive Statistics for 2011 National Health Interview Survey

(NHIS) Participants used in the analysis…………………………….24

2.

Logistic Regression Model for Predictors of Sleep Quantity……….26

3.

Multiple Regression Coefficients and Standard Errors for Predictor

of Self-Reported Health Status…………………….......................... 28

xi

1

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

As the numbers of unemployed people grow, work schedules change according to

business needs, and more people move into lower income brackets, more people are at

risk for poor health. Studies continue to try to explain why there is such a strong

correlation between health and socioeconomic status (SES) and why people with higher

SES have, on average, longer life expectancies and better overall health than those with

lower SES (Adler et al. 1994; Marmot 2004). Since sleeplessness and sleep disruption

are becoming increasingly common due to changing work patterns and other life-shaping

events, sleep insufficiency continues to become a serious public health problem that

needs recognition (CDC 2009). Ahead of their time, Aubert and White’s (1959)

landmark discussion on the sociology of sleep noticed the importance of sleep as a

cultural phenomenon and concluded that sleep was an important health-related event that

warrants additional study and should be present in the sociological literature. Even

though the link between SES and health is well established in the academic health

literature, the discussion related to the relationship between SES and sleep in relation to

health behaviors and health is minimal in the sociological literature. The goal of this

study is to determine if there is an association between SES and sleep duration and if

sleep quantity influences self-reported health status.

A survey of the existing literature suggests that the associations between SES,

sleep and health have not been examined in any recent studies. Therefore, this study

analyzes whether SES affects one’s sleep and health in more detail. Some researchers

suggest that previous literature has not included important factors related to SES and

2

sleep (Gellis et al. 2005) and that very few sociologists “have given sleep the attention it

deserves” (Williams 2002: 174). Although sleep has been widely overlooked in the

social sciences due to other pressing social matters, there is no doubt that there is a class

dimension in sleep behaviors, especially prominent among the homeless populations

(Taylor 1993). Williams (2002) reminds us, while we all have a need and right to sleep,

the western world has institutionalized the role of the sleeper who has specific rights,

duties, and patterns individual sleepers are obligated to maintain. Williams (2002)

continues his argument by suggesting that sleep is a social activity constructed by society,

government, and the sleep industry that have programmed our bodies to learn and

practice certain behaviors and techniques that can be controlled by those in power to

separate social classes as well as use it as a mechanism for surveillance. As we take a

closer look at how SES influences health, class differences regarding how long we sleep

and how sleep influences health will become more apparent.

Health studies suggest that appropriate levels of sleep play a vital role in one’s

health and functioning, physical activity (Atkinson and Davenne 2006), psychological

well-being (Hamilton et al. 2007, Pilcher and Ott 1998, Pilcher, Ginter and Sadowsky

1997), and academic performance and achievement in school (Buckhalt 2011). Yet,

Gellis et al. (2005) reports that at least 30% of American adults suffer from some sort of

insomnia or sleep disruption and those individuals of lower SES are more likely to suffer

from insomnia or complain about insomnia-related health problems. In addition, “certain

health risk behaviors appear to be associated with poor sleep quality including fighting,

suicide ideation, smoking, and alcohol use” (Vail-Smith, Felts, and Becker 2009:925).

3

Due to these claims and the varied results of existing research, this study addresses

whether sleep quantity influences health and how SES and other demographic factors

influence sleep and overall health.

SES may play a role in sleep duration and overall health. Gellis et al. (2005)

indicates that “education status is a risk factor for insomnia” and “insomnia is a condition

with numerous related factors” (p. 115) that can affect one’s overall health. Additionally,

Moore et al. (2002) finds that higher income, sleep, and better health are significantly

associated but cautions that causal direction warrants further study. Due to these claims

and the varied results of existing research, this study will test whether income and

education, are likely to predict optimal levels of sleep among adults. In addition, this

study will assess whether optimal sleep levels affects self-reported health status. Using

data from the 2011 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the principal source of

information on health in the U.S. for over fifty years and one of the few health surveys to

include data regarding sleep (CDC 2013), these variables will be tested as predictors of

optimal sleep and self-reported health status. The present study will run logistic

regression analysis to test the effect of income and education on optimal sleep levels. In

addition, this study will use multiple regression analysis to test whether optimal sleep

quantity is significant in determining health after controlling for other factors.

Since the majority of literature is limited to, understanding the determinants of

health, further expanding the scope of analysis to studying whether SES influences sleep

and overall health is essential to expanding the awareness of social inequalities in health.

The bulk of the findings suggest that poor health and prevalence of disease are issues that

4

need to be addressed among lower SES groups where health inequalities are most severe

(Adler et al. 1994). Although individuals are not in control of their SES, they may be

able to control other factors, like sleep that influence the relationship between SES and

health. Since education is one of the strongest predictors of health (Goesling 2007,

Winkleby et al. 1992), promoting positive health behaviors, including knowledge about

good sleep practices may lead individuals to make healthier choices and in turn have

healthier lives. As increasing economic stressors and financial insecurity continues to

affect people, it is important to study how these factors contribute to the association

between sleep and health. A review of the literature can highlight significant issues

surrounding differences in SES, sleep quantity and overall health.

5

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

The high rate of health-harming behaviors and sleep-related health problems

among lower SES groups has led health experts to find ways to reduce the socioeconomic

disparities in health (Adler et al. 2002, Gellis et al. 2005, Moore et al. 2002, and Pampel

et al. 2010). Considering that the unemployment rate in October 2012 is 7.9%, up from

an average of 5.8% from 1948 until 2012, the need to study the disparities in health is not

difficult to defend (Trading Economics 2012). The high rate of unemployment suggests

that more individuals may be susceptible to poor health due to higher stress, lower

incomes, and fewer educational opportunities. Even though knowledge about the

importance of sleep to our overall health is widespread and over 86% of adults agreed

that a lack of sleep was bad for their health (Pampel et al. 2010), relatively few studies

have recently tried to determine whether SES is associated with sleep quantity and health.

This study aims to fill the gaps in the literature on this subject by examining the

relationship between SES and sleep quantity in relation to overall health. Therefore, this

research will be a valuable addition to the existing literature so that others may continue

to explore how social determinants influence specific health behaviors and conditions

related to overall health.

Health and the Social Gradient

There are many theories covering the reasons why lower SES individual’s health

suffers when we, as a society, have health care facilities and the technology to assist

everyone. However, one of the major theories regarding health inequalities argues that

“health follows a social gradient” (Marmot 2004: 1). Marmot’s (2004) theory called “the

6

status syndrome” asserts that (1) one’s position in the social hierarchy determines their

health and length of life; (2) among all people, the higher the status, the healthier they

are; and (3) autonomy (how much control one has over their life) and social participation

are the biggest factors creating the social gradient in health. He further proposes that

differences in social and economic conditions affect the gradient. However, despite

environmental influences and personal behaviors, the causal direction of social factors

influencing the gradient can be misleading.

The task of understanding the casual direction of the relationship between SES

and health is daunting and very complex. While times are changing and the gradient can

change, Marmot (2004) warns that the social gradient doesn’t change as much as we

think it does. Regardless of what we do, those higher on the social gradient are healthier

than those lower on it. Therefore, while striving for a better position in the hierarchy may

be healthy, the components associated with the competition for status, particularly stress,

may negatively affect one’s health. Marmot (2004) suggests that our subtle awareness of

our relative position in the social hierarchy influences how we react to it. Marmot (2004)

calls on each of us individually to take responsibility for our awareness of our position in

the hierarchy and the way it affects our health, as well as meet our needs of autonomy

and social engagement that are essential to our health. Perhaps, insights from smaller

studies such as this will be useful in addressing health inequalities as well.

Defining SES and Social Determinants of Health

In previous studies, both SES and social determinants have varied considerably.

Social determinants of health are defined as the conditions (social, economic, and/or

7

physical) in the environment (work, home, school) that affect health and functioning

(Healthy People 2012). Since scholars define SES and approach social determinants of

health in numerous ways, often focusing on how they can improve measuring these

variables, it is imperative to clearly define and justify measures of SES and social

determinants in relation to health. As socioeconomic factors such as education and

income influence the outcome of health research differently, Braveman et al. (2006)

indicated that it was important to consider how we measure SES in relation to health so

that we can clearly understand influencing factors and accurately interpret our findings.

Additionally, Regidor’s (2006) research on defining and specifically identifying social

determinants of health suggests that as new social determinants of health emerge, it is

important to clearly define and clarify how these measures will be studied to avoid

ambiguity. In this study, SES is measured by educational level completed and individual

income earned. These variables were chosen because they are considered the standard

measurements of SES (Bravemen et. al. 2006). According to Adler and Newman

(2012:61), “education is perhaps the most basic SES component since is shapes future

occupational opportunities and earning potential,” while income provides the means to

purchase resources like health care, food, and housing. Sleep is measured by typical

hours of sleep duration per night. Therefore, to clarify, this study limits the analysis of

SES factors to education and income, and examines sleep duration or quantity, and a selfreported measure of overall health. As well, this study also limits this review to studies

of adults, as the dynamics of SES on sleep duration and overall health may be markedly

different in children.

8

SES and Health

Since numerous scholars continue to report that lower SES groups are at greater

risk for poor health, (Adler et al. 1994, Goldman and Smith 2002, Marmot 2004, Smith

1998, 2007) it is important to find out what researchers are currently saying about SES

and health. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC 2013),

social determinants of health, are social or physical conditions that affect health. “These

conditions are shaped by the amount of money, power, and resources that people have, all

of which are influenced by policy choices (CDC 2013). Social determinants of health

may be social, biological, physical, or psychological. However, scientists recognize

biology, health behaviors, access to health care, and social or physical environment as the

leading social determinants of health (CDC 2013).

Studies also suggest that the association between SES and health exists at all

levels of the SES hierarchy, not just those in poverty, meaning that at every level of SES,

differences in health occur (Adler et al. 1994, Marmot 2004, Smith 1998, 1999). Not

only do lower SES individuals have worse health than those with higher SES but that

individuals with the highest SES and individuals right below them in the same class also

have worse health, meaning that this gradient occurs within different levels of SES as

well as the overall differences (Adler et al., 1994; Friestad and Klepp, 2006, Marmot

2004). Therefore, it is important to examine how SES affects social determinants of

health at all levels of SES, not just among the most impoverished. Since the relationship

between SES and health is complex, a growing number of studies are taking a closer look

at how SES influences mediating factors, such as sleep.

9

Research continues to find that education, income, and similar social determinants

are the best predictors of health behaviors and health status (Adler et al. 1994, Goldman

and Smith 2002, Lantz et al. 1998). Multiple studies describe how higher SES groups

have better overall levels of health and longer life expectancies, while lower SES groups

have poorer health and shorter life expectancies (Adler et al. 1994, Grzywacz et al. 2004,

Lantz et al. 1998, Marmot 2004, Smith 2007). One classic explanation for these

disparities suggests that people with higher education have more opportunities to better

jobs and make more money, thus the ability to live in safer neighborhoods, attend better

schools, and have access to adequate health care. People with higher incomes are also

able to purchase healthier foods and enjoy additional social and leisure time while those

who may work longer hours for lower incomes cannot afford healthier foods, a gym

membership, or other extracurricular activities. People with lower levels of education

and income also have less access to stable work and affordable health care, thus leaving

them more susceptible to the effects of adverse health (CDC 2012). Since this reasoning

alone proves insufficient to explain the whole relationship, many look to other indirect

determinants that explain why health inequality exists at all levels of the SES hierarchy.

Mediators of the Relation between SES and Health

There seems to be multiple mediating factors influencing the relationship between

SES and health. According to reports by the CDC, (CDC 2012), social determinants of

health including health behaviors, biology, social and physical environment, and health

care all seem to be mediating factors in this relationship, suggesting that SES serves as a

precursor to other conditions that influence overall health. The determinants of SES

10

differences in health behaviors remain widely misunderstood but most often suggest that

the variation results from vast differences in the social and physical environments of

lower and higher SES groups (Pampel et. al 2010, Wardle and Steptoe 2002). “These

studies recognize that SES disparities in health behavior involve more than freely chosen

lifestyles” (Pampel et al.:350). Why lower SES groups engage in health-harming

behaviors more than high SES groups is alarming but socioeconomic conditions such as

income, education, race, and gender may indirectly influence health behaviors,

psychological issues, or environmental conditions that affect health (Adler and Newman

2002).

Since there are mixed explanations as how much social determinants influence

health, it is essential we look at biological, social, and environmental conditions that

could play a role in influencing health behaviors and health. For example, Pampel et al.

(2010) points out that among the many mechanisms that lower health in lower SES

groups; one of them suggests that lack of education limits knowledge and access to

information about health risks. In another example, Williams (2003) finds that low SES

impacts increased levels of childhood adversity, thus altering biological mechanisms that

trigger the likelihood of risk factors, such as hostility that alter future biological

functioning and affecting health. Other noted contributing factors to a person’s health

include childhood health influences, social standing, social position, physical and social

environment, sleep, stress, drinking, smoking and more (Adler et al. 1994, Grzywacz et

al. 2004, Lantz et al. 1998, Smith 1998, 1999, Wardle and Steptoe 2003). Some suggest

that attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles may influence health behaviors (Wardle

11

and Steptoe 2003) while others suggest differences in socioeconomic stratification itself

may lead to lower levels of social support, self-esteem, and sense of control over one’s

life (Lantz et al. 1998).

According to reports from the CDC (2012), negative health behaviors only

account for a small portion of health. However, these health behaviors have significant

effects on a person’s health and according to Adler and Newman (2002) account for

roughly half of all premature deaths and that together, health behaviors and exposure to

negative social and economic conditions account for 80% of premature mortality. They

also report that lower SES groups are more susceptible to environmental exposure to

noise and pollution, lack of social support, inadequate health care, chronic stress, and

more likely to engage in risky health behaviors to reduce stress (Adler and Newman

2002). Other studies continue to report that low SES individuals are more likely to

engage in unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, not exercising, and eating fast food,

more frequently regardless of their cost (Pampel et al. 2010). Similarly, researchers find

that people with lower SES were more likely to report poor sleep and poor health (Gellis

et al. 2005, Moore et al. 2002), physical ailments, and more likely to neglect personal

health care compared to those with higher SES (Goldman and Smith 2002).

Sleep

According to the National Sleep Foundation (2012), the optimal amount of sleep

for most adults seems to be between 7 to 9 hours a night. However, to Kripke (UCSD

2002) who conducted a longitudinal study of more than one million adults’ ages 30 to

102 found that people who get 6 to 7 hours of sleep a night have a lower death rate than

12

individuals who sleep 8 hours or more or less than 4 hours a night. Although common

belief suggests that optimal sleep is 8 hours or more, these individuals have a

significantly higher death rate compared to those who only sleep 6-7 hours. In an article

published by Time Magazine (Blue 2008), Kripke continues to explain, “There is just as

much risk associated with sleeping too long as with sleeping too short.” Therefore,

sleeping more may actually be worse than sleeping less (Blue 2008). Then again, in a

recent New York Times article, “Rethinking sleep,” Randal (2012) argues that common

belief regarding sleeping 8 hours a night is a relatively recent idea that is subject to

cultural interpretation. In addition, this idea was suggested over fifty years ago by Aubert

and White (1959), who discussed how sleep was subject to “Sociological Interpretation”

and what amount of sleep our body needs may actually be different from what society

says.. However, for this study, based on the evidence above, the optimal amount of sleep

will be between 7-9 hours a night since fewer hours of sleep may be too little and 9 hours

of sleep per night may lead to increased risk.

Sleep and Health

Studies reveal how sleep may influence health either negatively or positively. For

example, using data from the US National Health Survey (NHIS), Buxton and Marcelli

(2010) found evidence that both long and short sleep duration were significantly

associated with obesity, diabetes, hypertension, high blood pressure and cardiovascular

disease suggesting that optimal sleep duration directly and indirectly reduces health

problems. Lack of sleep has also been associated with certain health risk behaviors

(Vail-Smith et al. 2009), anxiety (Gregory et al. 2005), lower academic performance and

13

behavioral problems at school (Arman et al. 2010, Buckhalt 2011). In addition, evidence

by Atkinson and Davenne (2006) found that shiftwork or split work schedules causes

sleep disruption and lack of physical activity negatively influencing overall health. Thus,

sleep disruption may also influence one’s eating habits and influence their cardiovascular

safety (Atkinson and Davenne 2006).

Previous research also finds that sleep is significantly associated with overallhealth and well-being, and life satisfaction (Pilcher et al. 1997, Pilcher and Ott 1998).

Studies by Pilcher and Ott (1997) found evidence that healthy college students who

participated in a sleep study over a 3-month period reported both improved sleep and

improved overall health in reference to sleep quality. A follow-up study by Pilcher et al.

(1998) found again that better sleep was associated with better health and life satisfaction.

Consistent with this research, Hamilton et al. (2006) also found that optimal sleepers

reported less anxiety, depression, and better psychological well-being. In summary,

“sleep duration may be either a cause or consequence of well-being, and it is almost

certainly both” (Hamilton et al. 2006:160). While sleep may influence health either

negatively or positively, it will be important to examine the other factors, like SES that

influence sleep.

The Effects of SES on Sleep

Existing sleep research includes information relating to sleep itself, how sleep

affects health, and how others factors, including SES, may affect sleep. Among the few

studies that explore the SES and sleep association, evidence by Sekine et al. (2006) found

that social inequalities in sleep do exist. Lower SES individuals were more likely to

14

report poor sleep more than higher SES individuals were and that these inequalities could

influence health. In men, higher status employees had better sleep and health. While this

study showed that sleep quality played a mediating role in the relationship between SES

and health for men, it failed to show that sleep quantity directly played a mediating role

in the SES, health relationship. However, this study did show that the SES difference in

sleep contributed more to mental health than physical health suggesting that SES and

sleep are both important indicators of well-being.

Additional research also suggests that SES, sleep, and overall health are

significantly related (Moore et al. 2002). Moore et al. (2002) studied sleep in relation to

socioeconomic status and health. The authors collected information on socioeconomic

status, sleep, psychological and physical health from face-to-face interviews. They used

statistical analysis to determine the relationships and found that more education was

associated with higher income and higher levels of psychological and physical health.

The authors also found that more income and both measures of health were related to

sleep quality and quantity but not to overall SES. To conclude, the authors indicated that

while there is a significant association between measures, they could not draw

conclusions about the causal direction.

In contrast, rather than finding the SES measure of income to be statistically

significant, Gellis et al. (2005) found several measures of education to be associated with

sleep problems. Since previous literature had failed to study SES and insomnia, Gellis et

al. (2005) examined the prevalence of insomnia from a socioeconomic standpoint using a

random-digit dialing procedure to recruit participants to fill out questionnaires and sleep

15

diaries to report sleep and insomnia related conditions. In addition, socioeconomic status

was measured by three different educational levels to account for differences among

individuals and households. Gellis et al. (2005) found that individuals of lower

educational status were more likely to experience insomnia, greater subjective

impairment, and lower levels of overall health.

Since the sleep literature findings vary considerably by SES measures, some

studies consider that both socioeconomic and demographic conditions affect sleep.

Findings by Chapman et al. (2011) indicated that both unmarried men and women were

less likely than their married counterparts to report insufficient sleep. They also

suggested that the presence of children was associated with insufficient sleep. Additional

evidence by Tomfohr, Ancoli-Isreal, and Dimsdale (2010) found that racial differences

and childhood SES are associated with differences in sleep duration and quality. They

also found that there was an interaction between gender and SES but no interaction

between current SES, childhood SES, race, and sleep. Additional studies by Mezick et

al. (2008) also found differences in sleep patterns among different races. Their study

assessing sleep duration and quality found that blacks had shorter sleep duration in

comparison with others. Findings also indicated that lower SES is associated with poor

sleep quantity and disruption suggesting that lower SES individuals may be affected by

mediating factors like adverse environment, stress, and noise.

Arber et al. (2009) also examined how socioeconomic status (SES) and gender

affected sleep problems and whether SES differences in sleep problems could be

explained by certain demographic characteristics. Using interviews, the authors were

16

able to collect data about sleep problems, demographic and socioeconomic characteristics

that could measure whether or not these variables influence sleep problems. They found

that women report sleep problems more frequently than men do and that a significant

relationship with age occurred for women but not men. Significant associations were

also found for each SES measure, including income, employment, and home ownership.

Additional noted factors in this study indicated that smokers and those who report more

worries and depression are more likely to report sleep problems. These explanations are

consistent with previous literature on SES and health.

Mediators of the Relation between SES, Sleep, and Health

Explaining the SES gradient in sleep problems remains uncertain. However,

according to Arber et al. (2009), the same underlying mechanisms apply to sleep

problems as to health problems. These include structural disadvantage or environmental

conditions where noise, pollution, and crime are higher compromising both sleep quality

and quantity, psychological distress related to structural disadvantage, lifestyle or health

behaviors, and knowledge of sleep promoting behaviors. While these explanations may

not fully account for the strong association between poor health and sleep problems, this

is one of the few studies that does suggests that poor sleep may be one of the factors

through which lower SES negatively influences health (Arber et al. 2009).

In summary, evidence from a wide range of academic disciplines converges to

suggest that SES influences sleep duration and health. Some explanations explored how

SES influences health and health behaviors (sleep), while others like Marmot (2004)

focus on how the status syndrome influences the social gradient in health. Again, this

17

theory suggests that health follows a social gradient, meaning that those with higher SES

have in general higher health than those in lower SES groups. He further suggests that

not only will those in higher SES groups have better overall health; he explains that one’s

health is also determined by whether they have autonomy over their lives and their ability

to socially interact (Marmot 2004). According to Marmot (2004), education, income,

marriage, and employment are apparent factors that determine one’s social position that

will ultimately influence one’s health.

As suggested by Marmot (2004), social position influences the health gradient and

people are more likely to sleep better and be healthy if they have a steady income,

employment, and good outlook on life. Income and education may also increase one’s

likelihood of well-being and reduce the amount of stress in life since they have more

autonomy in their lives and don’t have to worry as much about their financial security or

future employment opportunities. Since the status syndrome (Marmot 2004) suggests

that the more autonomy and social interaction individuals have in their lives directly

influences their health, it seems that educational attainment would also lead to increased

knowledge relating to hygiene and taking care of oneself. In turn, this knowledge would

decrease the likelihood of someone having bad habits and getting sick.

Even though there are numerous studies on health, health behaviors and sleep,

very few discussed the relationship between SES, sleep, and health and as Aubert and

White (1959) suggested over fifty years ago, warrant further exploration. Studying

whether SES affects sleep is essential to understanding health and may help us “rethink

sleep” (Randal 2012) in a different way. In this study, the dependent variables I chose to

18

use were optimal sleep and self-reported health status. Additionally, measures of

education and income will determine SES. Based on Marmot’s (2004) status syndrome

and past research on the effects of SES on health behaviors and overall health, it is

expected that individuals with higher SES get more optimal sleep and have better health.

I also expect that lower SES levels negatively affect optimal sleep levels. That is, I

expect that lower SES individuals sleep is less than or greater than the optimal amount an

individual needs for adequate sleep. In addition, I expect that optimal sleep influences

self-reported health outcomes. Specifically, I predict that optimal amounts of sleep

predict self-reported health status.

19

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY

The aim of this study is to identify whether SES affects sleep duration and health

using data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Data from the 2011 adult

and person level files of the 2011 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) will be used

to measure the participant’s hours of sleep as well as their overall health. The NHIS is a

repeated cross-sectional survey on the health of the civilian non-institutionalized U.S.

population conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The

NHIS is the principal source of information on health and one of the major data

collection programs of the NCHS that is part of the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC). The U.S Census Bureau collects data for NHIS through household

interviews. The 2011 sample consisted of 39, 509 households and 101,875 persons

(NCHS 2011). Each annual sample consists of core questionnaire items revised

periodically. Topics of each questionnaire cover socio-demographic information, health

status information, health insurance information and related items pertaining to overall

health.

Variables

Sleep

Self-reported sleep quantity includes respondent’s answers to how many hours of

sleep they have in a 24-hour period. Sleep was measured in hours and is comprised of

respondents sleeping from 3-22 hours within a 24-hour period. For analytical purposes,

20

sleep was separated into two categories: optimal sleep coded 1 and non-optimal sleep

coded 0. Based on current sleep research, optimal sleep represents those who sleep

between 7-9 hours a night and non-optimal sleep represents those who sleep less than 7

hours a night and over 9 hours a night. Optimal sleep is the dependent variable for the

logistic regression analysis testing the effects of SES on sleep and the primary

independent variable for the multiple regression analysis testing the impact of optimal

sleep and SES on health.

Health status

The second dependent variable, self-reported health status, an ordinal level

variable is based on the question, “Would you say {your/ALIAS’s} health in general is

excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Five response categories ranged from

Excellent to Poor. For this analysis, ranges were recoded with the healthiest category

being the highest number. I focused on self-reported health status because I was

specifically interested in understanding whether optimal sleep and/or other demographic

characteristics predict the way people report their health. Therefore, this measurement is

the dependent variable for the regression analysis and testing and will be referred to as

“self-reported health status.”

Socioeconomic variables

For this study, there are two key independent variables measuring SES. These

socioeconomic variables include respondents’ education level completed and income

21

earned last year. The first key independent variable, Education is a continuous variable,

representing the highest number of years of school completed. Education was based on

the question, “What is the HIGHEST level of school {person has} completed or the

highest degree {person has} received? Please tell me the number from the card.”

Education was measured in categories from 0-21 grades or levels.

The second key independent variable, Income earned indicates individuals’

income earned last year. Since this variable is based on categorical data, income is not

continuous but based on categorical midpoints and computations. Income earned was

based on the question, “What is your best estimate of {person’s} earnings (include hourly

wages, salaries, tips and commissions) before taxes and deductions from ALL jobs and

businesses in [last calendar year in 4-digit format]? Income earned indicates the income

of the respondent from the lowest $01, to the highest of $75,000 and over. This range

includes multiple categories divided into $5000 increments and then raised to $10,000

increments at $25,000 and above.

Sociodemographic variables selected from the NHIS that may also predict a

person’s typical sleep duration and then overall health include respondent’s gender, age,

race, marital status, and employment status. The respondents’ gender (coded 1 for female

and 0 for male) now named Female represents their sex. Age, a continuous variable

measured in years describes the age of the person at the time of the survey and represents

ages 18 to 85+. Race is measured with four dummy variables: 1) Hispanic 2) Black 3)

Asian 4) other race (white is the reference category).

22

Six dummy variables indicate marital status: 1) married, spouse in the household

2) married, spouse not in the household 3) widowed 4) divorced 5) separated 6) living

with partner (never married is the reference category). Employment status is measured

with three dummy variables and omitting the reference category, had a job last week.

The dummy variables include: 1) no job last week, had job in past 12 months 2) no job

last week, no job in past 12 months 3) never worked.

Data Analysis Procedures

The quantitative data was analyzed using SPSS. Descriptive statistics were

performed on all variables. Logistic regression was used for analyzing the effect of

income and education on the dependent variable “Optimal sleep.” Multiple regression

was used for analyzing whether “optimal sleep” is significant in determining “selfreported health status” after controlling for other factors.

23

CHAPTER 4: RESULTS

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the sample. The sample shows that

65.4% of respondents get “optimal sleep” or 7-9 hours a night while 34.6% get “nonoptimal sleep” or less than 7 hours and/or more than 9 hours a night. The sample also

shows that the mean of self-reported health status is 3.85 or between good (3) and very

good (4) on a 5 point scale. For the SES variables, the average highest education

completed were those who finished the 12 grade, GED or equivalent (Mean=12.62, Std.

=5.292). Additionally, the mean total earnings last year were those earning $25,000$34,999.

Among sociodemographic variables, the sample is 55.1% female. The mean age

of the sample is 48.11 years. The racial identification of this sample ranges from the

majority as white only (53.0%), followed by Hispanic (24.1%), black only (15%), Asian

only (7.0%), and other races (1.0%). At the time of the survey, the majority of the

respondents had a job last week (57.4%), followed by those who did not have a job

within the last 12 months (29.7%). Those who did not have a job last week, but had a job

within the last 12 months (7.0%) and those who have never worked (5.7%) comprised the

remaining work status. As well, a large number of people are married (42.2%) while

23.5% have never married and 13.7% are divorced. These demographic data show the

majority get optimal sleep and have good to very good health. They have at least a high

school diploma and/or some college, average incomes and identify as white, have a job,

and are married.

24

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for 2011 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)

Participants used in the analysis.

Variables

Mean

Standard Deviation Percent

Hours of Sleep

Optimal Sleep (7-9 hours/night)

65.4%

Non-Optimal Sleep (<7->9 hours/night)

34.6%

Self-Reported Health Status

3.85

1.062

(Good-Very Good)

Excellent

34.4%

Very Good

29.6%

Good

25.2%

Fair

8.3%

Poor

2.4%

Education, in years

12.62

5.292

(12 grade, no diploma –GED or equivalent)

Total Earnings Last Year

6.06

3.055

($25,000-$34,999)

Age

48.11

18.178

Gender

Male

44.9%

Female

55.1%

Marital Status

Married-spouse in household

42.2%

Married-spouse not in household

1.6%

Widowed

9.3%

Divorced

13.7%

Separated

3.4%

Marital Status

Never married

23.5%

Living with partner

6.1%

Race

White only

53.0%

Black only

15.0%

Hispanic

24.1%

Asian

7.0%

Other race

1.0%

Work Status, last week, past 12 months

Had job last week

57.4%

No job last week, had job past 12 months

7.0%

No job last week, no job past 12 months

29.7%

Never worked

5.7%

25

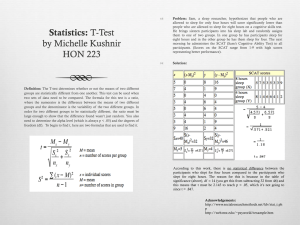

Table 2 presents the results of the logistic regression analysis predicting the odds

of optimal sleep. The variables used to predict the odds of getting optimal sleep include

education, income, age, race, gender, employment, and marital status. Table 2 displays

the characteristics that significantly predict sleep including education, being female,

black identification, being married, divorced, or separated, as well as not having a job last

week, and no job within the past twelve months. The Nagelkerke R square for Table 2

indicates that the model explains 2.0% of the variance in sleep quantity. The number of

cases included in this analysis is 101,875.

Among Socioeconomic variables, there is a 1.1% (OR =1.011, p=.05) increase in

odds of getting optimal sleep for each additional year of education completed while

income does not have a significant effect on sleep.

Among the control variables, marital status and racial identification stand out as

key demographic factors when predicting the odds of getting an optimal amount of sleep.

Compared to those who are never married, married respondents have an increase in odds

of optimal sleep of 9.6% (OR=1.096, p=.05), those divorced have a 19.4% (OR =.806,

p=.001) decrease in odds of optimal sleep and those separated have a 30.8% (OR =.692,

p=.001) decrease in odds of optimal sleep. Compared to those never married, the odds of

getting optimal sleep decrease for those divorced and/or separated. Additionally, there is

no significant difference in optimal sleep for those who identify as married but spouse not

living in the household, widowed, and living with a partner compared to never married.

26

Table 2. Logistic Regression Model for Predictors of Sleep Quantity.

Variables

Income

Exp(B)

.999

Education

1.011*

Age

1.000

Gender (Male omitted) Female

1.082*

Marital Status (Never married omitted):

Married

Married-spouse not living in household

Widowed

Divorced

Separated

Living with Partner

1.096*

.990

.912

.806***

.692***

.915

Race (White omitted):

Hispanic

Black

Asian

Other race

1.054

.587***

1.055

.868

Employment Status (Had job last week omitted):

No job last week, had job past 12 months

No job last week, no job past 12 months

Never worked

1.054

.857**

1.138

N=101875 total

Chi-Square = 266.339

*p< .05, ** p<.01, ***p<.001

27

In terms of race, for blacks there is a 41.3% (OR =.587, p=.001) decrease in odds of

getting optimal sleep compared to whites. Those who identify as Hispanic, Asian, and

other race show no difference in getting optimal sleep compared to whites. Clearly,

marriage and racially identifying as white contribute positively to optimal sleep.

Employment status and gender are other characteristics that have a significant

impact on the odds of getting optimal sleep. Compared to those who had a job last week,

those who have not had a job in the past 12 months have a 14.3% (OR =.857, p=.01)

decrease in odds of getting optimal sleep. There is no significant difference for those

who did not have a job last week but had a job within the past 12 months and those who

have never worked. Compared to males, female have 8.2% (OR =1.082, p=.05) greater

odds of getting optimal sleep. Having a job and being female increases one’s odds of

getting optimal sleep.

Table 3 presents multiple regression coefficients for predictors of reported health

status. Multiple regression analysis was run to determine the influence of optimal sleep

and SES on self-reported health status. Results show that 9.8% of the variation in the

dependent variable, self-reported health, is explained by the independent and control

variables (R2= .098, p= 000).

Self-reported health status was measured using a 5 point scale ranging from “poor

health” (1) to the “excellent health” (5), with “fair” (2), “good” (3) and “very good” (4)

health as mid-range options. As expected, optimal sleep is a significant factor in

determining self-reported health status. Compared to those with non-optimal sleep, those

28

Table 3. Multiple Regression Coefficients and Standard Errors for Predictors of Self-Reported

Health Status.

Variables

Optimal Sleep (7-9 hrs. /night)

Income

Education

Age

Gender (Male omitted):

Female

Marital Status (Never married omitted):

Married

Married-spouse not living in household

Divorced

Separated

Living with Partner

Race (White omitted):

Hispanic

Black

Asian

Other race

Employment Status (Had job last week omitted):

No job last week, had job past 12 months

B

.203***

(.014)

.036**

(.002)

044***

(.002)

.011***

(.001)

-.020

(.014)

.114***

(.018)

.104

(.056)

.008

(.024)

-.004

(.039)

-.001

(.028)

.067**

(.019)

.151***

(.020)

-.070*

(.028)

-.184*

.130***

(.024)

No job last week, no job past 12 months

.142***

(.025)

Never worked

.182***

(.043)

Intercept

3.334***

R Square

.098

F

111.154

______________________________________________________________________________

*p< .05, ** p<.01, ***p<.001 Note: Number in parenthesis is the standard error. Note: SelfReported Health Status (1=Poor, 2=Fair, 3=Good, 4=Very good, 5=Excellent)

29

with optimal sleep report .203 levels higher health on the 1-5 health scale (B=.203,

p=.001). In regards to education, a one year increase in education, increases health

by.044 (B=.044, p=.001) units on this 1-5 scale. As previously mentioned in the

research, education positively influences health. In addition, for every categorical

increase of income, health increases by .036 (B=.036, p=.001) levels of health on the 5point scale.

Age is also a statistically significant factor in self-reported health status. For

every year of age increase, health decreases by .011 (B=-.011, p=.001) levels on the scale

ranging 1-5. This indicates that after controlling for other factors, older people are

reporting lower levels of health.

In regards to marital status, compared to those who have never married, the mean

level health for married individuals is .114 (B=.114, p=.001) units higher, controlling for

the other variables in the model. Mean health levels for those not living with their

spouse, widowed, separated, and/or living with a partner are not significantly different

from the mean health level for those who have never married. However, in terms of

employment. status, compared to those who have a job, the mean level of health for

unemployed respondents who have worked within the past 12 months had .130 (B=-.130,

p=.001) units lower health, the mean level of health for unemployed respondents who

have not worked within the past 12 months had .142 (B=-.142, p=.001) units of lower

health, and the mean health for respondents who have never worked had.182 (B=-.182,

p=.001) units of lower health on the 5-point scale.

30

For race, compared to white respondents levels of health, the mean health levels

for Hispanic respondents health decreases by .067 (B=-.067, p=.01) units of lower health,

black respondents health decreases by .151 (B=-.151, p =.001) units of lower health,

Asian respondents heath decreases by .070 (B=-.070, p=.05) units of lower health, and

other races respondents health decreases by .184 (B=-.184. p=.05) units of lower health

on the 5-point scale, controlling for other variables in the model

The standardized coefficients (not shown) indicate that the strongest predictor of

health is age followed by education and then income. However, Optimal sleep is the 4th

strongest predictors of health. The standardized coefficient for age is -.170 followed by

education at .147, income earned last year at .116, and optimal sleep at .100.

In Summary, Table 2 showed that certain significant variables describe those

who are predicted to sleep optimally or less than optimally even though the regression

model only explained a fairly small (2%) of variance in sleep. Increasing one’s education

level, being female and married increases the odds of optimal sleep, while those who are

divorced, separated, and/or unemployed for over a year have decreased odds for optimal

sleep. People who racially identify as black are also at decreased odds of getting optimal

sleep.

Table 3 showed those who get optimal sleep have better health than those with

non-optimal sleep. Slightly higher than the previous model, 9.8% of the variance in

health was explained by the variables in this model. Consistent with the previous

literature, compared to those with lower education and lower income levels, those with

31

higher education and income levels have better health. As well, as age increases, health

decreases.

32

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study is to add to the sociological literature on SES, sleep and

health by investigating the odds of different SES groups getting optimal sleep (7-9

hours), as well as analyzing how SES and optimal sleep influence self-reported health

status in adults. Although I hypothesized that SES factors may affect optimal sleep, the

results of this study revealed that increasing education levels were associated with

increased odds of getting optimal sleep while there was no difference in terms of income.

However, this research does support past research findings that indicate social

inequalities in sleep do exist (Sekine et al. 2006). The findings in this research support

previous studies that found education status (Gellis et al. 2005; Moore et al. 2002),

marital status (Chapman et al. 2011), race (Mezick et al. 2008;Tomfohr et al. 2010),

gender (Arber et al. 2009; Sekine et al. 2006), and employment status (Sekine et al. 2006)

influence sleep quantity in adults.

In the current research, more education was associated with an increase in odds of

getting optimal sleep while income was not. These results are different from Moore et al.

(2002) who found that income, not education was associated with better sleep.

According to Moore et al. (2002), education may influence sleep by increasing income

levels and thus, higher levels of health (Moore et al. 2002). However, the present results

are more similar to the results by Gellis et al. (2005) who found that with each increase in

education levels, the likelihood of insomnia decreases suggesting that more education

33

increases the likelihood of more sleep, thereby reducing the odds that lifestyle behaviors

are associated with sleep and insomnia (Winkleby et al. 1992).

Additional results show, compared to those who have never married, those who

are married have an increase in odds of getting optimal sleep. This is consistent with

prior research by Chapman et al. (2011: 348), “indicating that marital status plays an

important role in adult perceived sleep sufficiency.” Chapman et al. (2011) found that

married respondents slept better than those who had never married or were previously

married. This study’s results also showed a significant decrease in odds of getting

optimal sleep for those divorced or separated. These results are similar to the findings of

Arber et al. (2009) who found that those divorced or separated report the worst sleep.

This study also supports past research that finds race influences the chances of

getting optimal sleep. The results of this study show that for black respondents there is a

41.3 % (Table 2) decrease in odds of getting optimal sleep compared to white

respondents. These results are consistent with past research by Tomfohr et al. (2010)

who found that black participants had worse sleep than white participants and that after

controlling for other demographic information; race is an important factor when studying

sleep outcomes. Mezick et al. (2008) also found that blacks had shorter sleep compared

with others but suggests that individuals in lower SES groups, including blacks may be at

higher risk for sleep disturbances due to a variety of social and environmental factors.

In this study, having steady employment seems to increase the odds of getting

optimal sleep. Compared to those employed, those not working consistently had a

34

decrease in odds of getting optimal sleep. Previous literature confirms that

unemployment or being economically inactive increase the odds of sleep problems

(Arber et al. 2009) and that those with successful employment and higher ranked jobs

also get better sleep (Sekine et al. 2005).

While most results from this study seem to be consistent with previous literature

on the effects of SES and other demographic variables on sleep, the results of this study

in terms of gender are inconsistent with previous literature. This study showed that

compared to men, females have greater odds of getting optimal sleep. This is

inconsistent with previous studies by Sekine et al. (2005) that found no significant

differences in sleep compared to men or by Chapman et al. (2012) who found that women

were more likely to report less than optimal amounts of sleep. Similarly, Arber et al.

(2009) found that more women than men report sleep problems and suggested that the

difference is related to more socioeconomic disadvantage and worries from their more

disadvantaged circumstances. While this past research may still be true, it seems that

other factors may influence who gets optimal sleep more than gender.

While the results of this study were statistically significant, many of the

relationships in this study, including gender, were modest. However, it was surprising to

see marital status and race as key factors predicting sleep. It seems that those married

have less stress and may have higher levels of well-being than those who aren’t married.

This is also consistent with Marmot (2004) who explains that marriage provides social

and financial support that benefits overall health and reduces the risk of poor health

35

behaviors. It also seems that those who racially identify as black may have higher levels

of stress due to disadvantaged circumstances including a health disadvantage (Marmot

2004).

The results of this study showed the strongest predictor of health is age, followed

by education and income. This is also consistent with past research that found that

education and income are the best predictors of health (Adler et al. 1994, Goldman and

Smith 2002, and Lantz et al. 1998). As discussed earlier in the literature, one explanation

for this suggests that people with higher educations have more opportunities to better

jobs, more income, and other factors that promote wellness (CDC 2012). Other research

suggested that education might be the strongest predictor of good health because

education may protect one’s health by influencing health behaviors, values, and problemsolving skills that may help promote positive attitudes about health (Winkleby et al.

1992). Similarly to Marmot’s (2004) status syndrome theory, Winkleby et al. (1992),

suggests that educational attainment may increase one’s access to preventative services,

membership in social or peer groups that promote health behaviors and self-efficacy.

The present study also adds legitimacy to previous findings that indicate that

optimal sleep is a significant factor in determining the self-reported health status of

adults. The results show that compared to those with non-optimal sleep, those with

optimal sleep have better health. As hypothesized earlier, optimal sleep does affect one’s

health. While common knowledge may dictate this fact, previous research also found

that that better sleep was associated with improved physical health, well-being (Atkinson

36

and Davenne 2006, Pilcher and Ott 1998), and psychological well-being and health

(Hamilton et al. 2006, Pilcher et al. 1997).

Other results showed that those who married have higher levels of health

compared to those who never married. Those who didn’t live with their spouse,

widowed, separated, and/or living with their partners were not significant predictors of

health. According to Marmot (2004), marriage protects both men and women in terms of

disease and death. Married individuals have lower mortality than those who are

unmarried. Those unmarried lack social support and may be more susceptible to adverse

health behaviors (Marmot 2004). Thus, marriage is an important indicator of health.

The results of this study are consistent to Marmot’s (2004) theory suggesting that

many factors contribute to the inequalities in health including but not limited to

education, income, marital status, employment, gender, and so much more. According to

Marmot (2004), the health gradient affects all people. However, those with higher

incomes have lower mortality rates and better overall health. Those with higher incomes

are more likely to have more education and those with more education are likely to make

more money, both contributing to the gradient in health. In addition to education and

income, employment status also affects health. Evidence described by Marmot (2004:

135) also shows that employment ranking also predicts health while “unemployment

increased mortality,” however, the reasons why are more complex. While unemployment

decreases one’s income and social interaction, it may also increase levels of depression,

stress, and anxiety, thus increasing the likelihood of ill health and bad health behaviors.

37

In addition, it increases levels of job insecurity and changes one’s expectations about the

fate of their employment, thus, leading to the deterioration of one’s health (Marmot

2004).

The data from this study support the hypothesis that the presence of inequalities

exist in sleep and overall health. These results also support Marmot’s (2004) theory that

many factors influence the social gradient in health and that status plays a key role in

health. Overall, recognition in the importance that status influences one’s sleep and

health by guiding one’s sense of control over their life and social position in the hierarchy

ought to be addressed, for the betterment of society. These results also suggest the need

for instruction and education regarding the importance of sleep to overall health. Ideally,

such education would encourage health sleep patterns, which may contribute to the

reduction of inequalities in health.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study is the use of the NHIS, a well-recognized and long

running survey. Although the dataset provided large numbers for the sample size of

adults that were surveyed for demographic and health information, the survey didn’t

address work type and sleep in detail; leaving limited variables to draw from for

statistical analysis. Secondly, the responses to the survey still rely heavily on selfreported status. Anytime survey respondents are self-reporting, it is important to

remember that some respondents may not be open to answering all questions, especially

those relating to undesirable or specific health behaviors that may be difficult to access

38

correctly and discuss. Thus, the reliability of the responses may have been influenced by

inaccuracies or external factors.

Areas of Further Research

Although the data provided added a great deal of information on sleep quantity,

specifically optimal sleep and health, a follow up study focusing on non-optimal sleep

and sleep quality would be beneficial to understanding who and why people sleep the

way they do and how it affects their health. Although the data were collected using the

NHIS, a future study would benefit from a mixed methods approach. Collecting detailed

information about the respondent’s habits, health behaviors and routines using interviews,

focus groups, and other survey methods would add to the explanation of what predicts

sleep and whether sleep affects health. Continued focus on the sociology of sleep is an

essential part of our culture that warrants further investigation.

39

REFERENCES

Adler, Nancy E., Thomas Boyce, Margaret A. Chesney, Sheldon Cohen, Susan Folkman,

Robert L. Kahn, and S. Leonard Syme. 1994. “Socioeconomic Status and

Health: The Challenge of the Gradient.” American Psychologist 49(1):15-24.

Adler, Nancy E. and Katherine Newman. 2002. “Socioeconomic Disparities in Health:

Pathways and Policies.” Health Affairs 21(2):60-76.

Arber, Sara, Marcos Bote, and Robert Meadows. 2009. “Gender and socio-economic

patterning of self-reported sleep problems in Britain.” Social Science & Medicine

68:281-289.

Arman, Ayse Rodopman, Pinar Ay, Nese Perdahli Fis, Refika Ersu, Ahmet Topuzoglu,

Ugur Isik, and Meral Berkem. 2010. “Association of sleep duration with socioeconomic status and behavioral problems among schoolchildren.” Acta

Paediatrica 100:420-424.

Atkinson, Greg and Damien Davenne. 2007. “Relationships between sleep, physical

activity and human health.” Physiology and Behavior 90:229-235.

Aubert, Vilelm and Harrison White. 1959. “Sleep: A Sociological Interpretation. I.”

Acta Sociologica 4(2): 46-54.

Blue, Laura. 2008. “How Much Sleep Do You Really Need?” Time, April 8. Retrieved

September 27, 2012

(http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1812420,00.html).

40

Braveman, Paula A., Catherine Cubbin, Susan Egerter, Sekai Chideya, Kristen S. Marchi,

Marilyn Metzler, and Samuel Posner. 2005. “Socioeconomic Status in Health

Research: One Size Does Not Fit All.” (Reprinted) JAMA 294(22):2879-2888.

Buckhalt, Joseph A. 2011. “Insufficient Sleep and the Socioeconomic Status

Achievement Gap.” Child Development Perspectives 5(1):59-65.

Buxton, Orfeu M. and Enrico Marcelli. 2010. “Short and long sleep are positively

associated with obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease among

adults in the United States.” Social Science & Medicine 71:1027-1036.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009. “Perceived Insufficient Rest or Sleep

Among Adults---United States, 2008.” MMWR 58(42): 1175-1179. Retrieved

August 2, 2013.

(http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5842a2.htm).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012. “Social Determinants of Health.”

Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved September

27, 2012. (http://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/FAQ.html).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. “Social Determinants of Health:

Definitions.” Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Retrieved August 2, 2013.

(http://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/Definitions.html )

Chapman, Daniel P., Anne G. Wheaton, Geraldine S. Perry, Stephanie L. Sturgis, Tara

W. Strine, and Janet B. Croft. 2012. “Household Demographics and Perceived

Insufficient Sleep Among US Adults.” J Community Health 37:344-349.

41

Friestad, Christine and Knut-Inge Klepp. 2006. “Socioeconomic status and health

behavior patterns through adolescence: Results from a prospective cohort study

in Norway.” European Journal of Public Health 16(1):41-47.

Gellis, Les A., Kenneth L. Lichstein, H. Heith Durrence, Daniel J. Taylor, Isabel C.

Scarinci, Andrew J. Bush, and Brant W. Ridel. 2005. “Socioeconomic Status and

Insomnia.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 114(1):111-118.

Goesling, Brian. 2007. “The Rising Significance of Education for Health?” Social

Forces 85(4):1621-1644.

Goldman, Dana P. and James P. Smith. 2002. “Can Patient Self-Management Help

Explain the SES Health Gradient?” Proceedings of the National Academy of

Science of the United States of America 99(6):10929-10934.

Gregory, Alice M., Thalia C. Eley, Thomas G. O’Connor, Fruhling V. Rijsdijk, and

Robert Plomin. 2005. “Family influence on the association between sleep

problems and anxiety in a large sample of pre-school aged twins.” Personality

and Individual Differences 39: 1337-1348.

Grzywacz, Joseph G., David M. Almeida, Shevaun D. Neupert, and Susan L. Ettner.

2004. “Socioeconomic Status and Health: A Micro-Level Analysis of Exposure

and Vulnerability to Daily Stressors.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior

45(1):1-16.

Hamilton, N. A., C. A. Nelson, N. Stevens, and Health Kitzman. 2007. “Sleep and

Psychological Well-Being.” Social Indicators Research 82(1):147-163.

42

Healthy People.gov. 2012. “Social Determinants of Health.” Washington DC: U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, Retrieved December 1, 2012

(http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid

=39 ).

Lantz, Paula M., James S. House, James M. Lepkowski, David R. Williams, Richard P.

Mero, and Jieming Chen. 1998. “Socioeconomic Factors, Health Behaviors, and

Mortality: Results from a Nationally Representative Prospective Study of US

Adults.” JAMA 279(21):1703-1708.

Marmot, Michael. 2004. The Status Syndrome: How Social Standing Affects Our

Health and Longevity. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

Mezick, Elizabeth J., Karen A. Matthews, Martia Hall, Patrick J. Strollo Jr., Daniel J.

Buysse, Thomas W. Karmarch, Jane F. Owens, and Steven E. Reis. 2008.

“Influence of Race and Socioeconomic Status on Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep SCORE

Project.” Psychosomatic Medicine 70(4):410—416.

Moore, Philip J., Nancy E. Adler, David R. Williams, and James S. Jackson. 2002.

“Socioeconomic Status and Health: The Role of Sleep.” Psychosomatic

Medicine 64:337-344.

National Center for Health Statistics. Data File Documentation, National Health

Interview Survey, 2011 (machine-readable data file and documentation).

National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

Hyattsville, Maryland. 2012.

43

National Sleep Foundation. 2012. “How Much Sleep Do We Really Need?” Arlington,

VA: National Sleep Foundation. Retrieved November 19, 2012

(http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/how-sleep-works/how-much-sleep-dowe-really-need ).

Pampel, Fred C., Partrick M. Krueger, and Justin T. Denney. 2010. “Socioeconomic

Disparities in Health Behaviors.” The Annual Review of Sociology 36: 349-370.

Pilcher, June J., Douglas R. Ginter, and Brigitte Sadowsky. 1997. “Sleep Quality Versus

Sleep Quantity: Relationships Between Sleep and Measures of Health, WellBeing and Sleepiness in College Students.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research

42(6):583-596.

Pilcher J. J and Ott ES. 1998. “The Relationships between Sleep and Measures of

Health and Well-Being in College Students: a Repeated Measures Approach.”

Behavioral Medicine 23(4):170-178.

Randall, David A. 2012. “Rethinking Sleep.” The New York Times, September 22, pp

Regidor, Enrique. 2006. “Theory and Methods: Social determinants of health: a veil that

hides socioeconomic position and its relation with health.” Journal of

Epidemiology and Community Health 60(10):896-901.

Sekine, Michikazu, Tarani Chandola, Pekka Martikainen, David McGeoghegan, Michael

Marmot and Sadanobu Kagamimori. 2005. “Explaining social inequalities in

health by sleep: the Japanese civil servants study.” Journal of Public Health

28(1):63-70.

44

Smith, James P. 1998. “Socioeconomic Status and Health.” The American Economic

Review 88(2):192-196.

------. 1999. “Healthy Bodies and Thick Wallets: The Dual Relation between Health

and Economic Status.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 13(2):145-166.

------. 2007. “The Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Health over the Life-Course.” The

Journal of Human Resources 42(4):739-764.

Taylor, Brian. 1993. “Unconsciousness and Society: The Sociology of Sleep.”

International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 6(3):463-471.

Tomfohr, Lianne M., Sonia Ancoli-Israel, and Joel E. Dimsdale. 2010. “Childhood

Socioeconomic Status and Race are Associated with Adult Sleep.” Behavioral

Sleep Medicine 8:219-230.

Trading Economics. 2012. “United States Unemployment Rate.”

TradingEconomics.com, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, November 2. Retrieved

November 8, 2012 (http://www.tradingeconomics.com/unitedstates/unemployment-rate).

UCSD School of Medicine NEWS: Health Sciences Communications. 2002. “Sleep

less, live longer?” UCSB Health Sciences Communications HealthBeat, February

14. Retrieved September 27, 2012

(http://www.health.ucsd.edu/news/2002_08_kripke.html).

Vail-Smith, Karen, Michael W. Felts, and Craig Becker. 2009. “Relationships between

Sleep Quality and Health Risk Behaviors in Undergraduate College Students.”

College Student Journal 43(3):924-927.

45

Wardle, J. and A. Steptoe. 2003. “Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs

about health lifestyles.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57:440443.

Williams, Redford B. 2003. “Invited Commentary: Socioeconomic Status, Hostility,

and Health Behaviors-Does it Matter Which Comes First?” American Journal of

Epidemiology 158(8):743-746.

Williams, Simon J. 2002. “Sleep and Health: Sociological reflections on dormant